Dallas Wolf

Hesychastic hermit

Homepage: https://firstthoughtsofgod.com

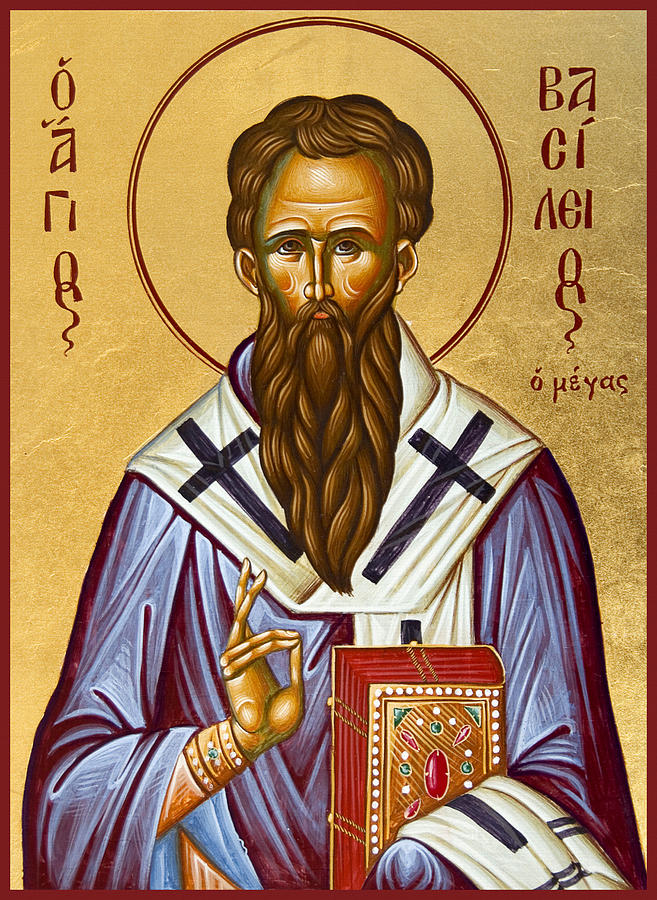

St. Basil the Great: “Homily About Ascesis – How a Monk Should be Adorned”

Posted in Ekklesia and church, Monasticism, Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians on April 8, 2023

St. Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great (330 – January 379), was a bishop of Caesarea Mazaca in Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey). He was an influential theologian who supported the Nicene Creed and opposed the heresies of the early Christian church. Together with Pachomius, he is remembered as a father of communal (coenobitic) monasticism in Eastern Christianity. Basil, together with his brother Gregory of Nyssa and his friend Gregory of Nazianzus, are collectively referred to as the Cappadocian Fathers.

“The monk, above all, must not possess anything in his life. He must have bodily isolation, proper clothing, a moderate tone of voice, and discipline speech; he must not cause a ruckus about the food and drink and he must eat in silence; he must be silent before his elders and be attentive to wiser men; he must love his peers and advise those junior in a loving way; he must move away from the immoral and the carnal and the sophisticated; he must think much and say less; he must not become impudent in his words, nor gossip and not be amenable to laughter; he must be adorned with shame, directing his gaze to the ground and his soul upward; he must not object with words of contention but rather be compliant; he must work with his hands and always keep in remembrance the end of this age; he must rejoice with hope, endure sadness, pray unceasingly and thank God for everything; he must be humble towards all and hate pride; he must be vigilant in keeping his heart pure of any evil thought; he must gather treasures in Heaven by keeping the commandments, examine himself for his thoughts and actions each day and not be involved in vain things of life and in idle talk; he must not examine inquisitively the life of idle people, but imitate the lives of the Holy Fathers; he must be happy with those who achieve virtue and not be envious; he must suffer with those suffering and weep with them and be sorry for them, but not criticise them; he must not reproach one who returns from his sin and never justify himself. Above all else he must confess before God and the men that he is a sinner and admonish the unruly, strengthen the faint-hearted, minister unto the sick and washed the feet of the saints; he must attend to hospitality and brotherly love, to be at peace with those who have the same faith and abhor the heretics; he must read the canonical books and not open even a single one of the occult; he must not talk about the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, but think and confess the uncreated and consubstantial Trinity with courage, and tell those who ask that there is the need of to be baptised, as we have received it from the tradition, to believe, as we have confessed it according to our baptism, and to glorify God, as we have believed.”

~ from: The Monastic Rule of St. Basil the Great

St. Gregory of Sinai: ‘Sowing in the Light’

Posted in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, Monasticism, Patristic Pearls on April 7, 2023

St. Gregory of Sinai (c. 1260s -1346) – was a well-travelled Greek Christian monk and writer from Smyrna (modern-day İzmir, Turkey). He was instrumental in the emergence of hesychasm on Mount Athos in the early 14th century. He was a contemporary of St. Gregory Palamas.

“According to St. Paul (cf. Rom. 15:16), you “minister” the Gospel only when, having yourself participated in the light of Christ, you can pass it on actively to others. Then you sow the Logos like a divine seed in the fields of your listeners’ souls. ‘Let your speech be always filled with grace’, says St Paul (Col. 4:6), ‘seasoned’ with divine goodness. Then it will impart grace to those who listen to you with faith. Elsewhere St. Paul, calling the teachers tillers and their pupils the field they till (cf. II Tim. 2:6), wisely presents the former as ploughers and sowers of the divine Logos and the latter as the fertile soil, yielding a rich crop of virtues. True ministry is not simply a celebration of sacred rites; it also involves participation in divine blessings and the communication of these blessings to others.”

~ from: The Philokalia

St. Macrina and the Healing of the Soldier’s Daughter

Posted in Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians, Women in Early Christianity on April 6, 2023

St. Macrina the Younger (ca. AD 327 – July 379), was the older sister of three Cappadocian Saints and Bishops: Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Peter of Sebasteia. She was also friends with St. Gregory of Nanzianzus. Macrina transformed one of her family’s rural estates in Pontus (modern Turkey) into a monastery for ascetic virgins who came from both an aristocratic and non-aristocratic backgrounds. All members, including those from her own household, were free and ex-slaves received the same rights and obligations as their former masters. St. Basil established a men’s monastery nearby. Macrina was so well respected and loved by her younger brother, Gregory, that he wrote two books about her virtues, holiness, and intellect soon after her death in AD 379: The Life of Saint Macrina and On the Soul and the Resurrection. The post below is an excerpt from The Life of Saint Macrina, written in about AD 381.

“Along the way [from Macrina’s funeral], a distinguished military man who had command of a garrison in a little town of the district of Pontus, called Sebastopolis, and who lived there with his subordinates, came with the kindly intentions to meet me [Gregory of Nyssa] when I arrived there. He had heard of our misfortune [the death of Macrina] and he took it badly (for, in fact, he was related to our family by kinship and also by close friendship). He gave me an account of a miracle worked by Macrina; and this will be the last event I shall record in my story before concluding my narrative. When we stopped weeping and were standing in conversation, he said to me, “Hear what a great good has departed from human life.” And with this he stated his story.

“It happened that my wife and I once desired to visit that powerhouse of virtue; for that’s what I think that place should be called in which the blessed soul spent her life. Our little daughter was also with us and she suffered from an eye ailment as a result of an infectious disease. And it was a hideous and pitiful sight, since the membrane around the pupil was swollen and because of the disease had taken on a whitish tinge. As we entered that divine place, we separated, my wife and I, to make our visit to those who lived a life of philosophy1 therein, I going to the monks’ enclosure where your brother, Peter [of Sebaste], was abbot, and my wife entering the convent to be with the holy one. After a suitable interval had passed, we decided it was time to leave the monastery retreat and we were already getting ready to go when the same, friendly invitation came to us from both quarters. Your brother asked me to stay and take part in the philosophic table, and the blessed Macrina would not permit my wife to leave, but she held our little daughter in her arms and said that she would not give her back until she had given them a meal and offered them the wealth of philosophy; and, as you might have expected, she kissed the little girl and was putting her lips to the girl’s eyes, when she noticed the infection around the pupil and said, “If you do me the favor of sharing our table with us, I will give you in return a reward to match your courtesy.” The little girl’s mother asked what it might be and the great Macrina replied, “It is an ointment I have that has the power to heal the eye infection.” When after this a message reached me from the women’s quarters telling me of Macrina’s promise, we gladly stayed, counting of little consequence the necessity which pressed us to make our way back home.

Finally the feasting was over and our souls were full. The great Peter with his own hands had entertained and cheered us royally, and the holy Macrina took leave of my wife with every courtesy one could wish for. And so, bright and joyful, we started back home along the same road, each of us telling the other what happened to each as we went along. And I recounted all I had seen and heard in the men’s enclosure, while she told me every little thing in detail, like a history book, and thought that she should omit nothing, not even the least significant details. On she went telling me about everything in order, as if in a narrative, and when she came to the part where a promise of a cure for the eye had been made, she interrupted the narrative to exclaim, “What’s the matter with us! How did we forget the promise she made us, the special eye ointment?” And I was angry about our negligence and summoned some one to run back quickly to ask for the medicine, when our baby, who was in her nurse’s arms, looked, as it happened, towards her mother. And the mother gazed intently at the child’s eyes and then loudly exclaimed with joy and surprise, “Stop being angry at our negligence! Look! There’s nothing missing of what she promised us, but the true medicine with which she heals diseases, the healing which comes from prayer, she has given us and it has already done its work, there’s nothing whatsoever left of the eye disease, all healed by that divine medicine!” And as she was saying this, she picked the child up in her arms and put her down in mine. And then I too understood the incredible miracles of the gospel, which I had not believed in, and exclaimed: “What a great thing it is when the hand of God restores sight to the blind, when today his servant heals such sicknesses by her faith in Him, an event no less impressive than those miracles!” All the while he was saying this, his voice was choked with emotion and the tears flowed into his story. This then is what I heard from the soldier.”

~ from The Life of Saint Macrina, by St. Gregory of Nyssa

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Philosophy as the ideal of the Christian monastic life plays a central role in The Life of Saint Macrina (LSM) and will undoubtedly seem strange, even alien, to modern ears long accustomed to the scholasticism and secularization of academic disciplines. However, the essential and organic unity of the spiritual, intellectual, and physical ways of life, central to the monastic Rule of St. Basil, even yields such a remarkable phrase in the LSM as “the philosophic table”. This usage accurately reflects St. Gregory’s fourth-century Christian understanding of “philosophy”, i.e., love of wisdom, passion for the truth, care of the soul, contemplation (theoria), and ascetic physical discipline which spurns attachment to material things while recognizing that the body will be restored to its true God-created stature by the resurrection.

St. Basil the Great: “On the Holy Spirit”

Posted in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Monasticism, Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians, The Holy Trinity, Theology on April 6, 2023

St. Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great (330 – January 379), was a bishop of Caesarea Mazaca in Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey). He was an influential theologian who supported the Nicene Creed and opposed the heresies of the early Christian church. Together with Pachomius, he is remembered as a father of communal (coenobitic) monasticism in Eastern Christianity. Basil, together with his brother Gregory of Nyssa and his friend Gregory of Nazianzus, are collectively referred to as the Cappadocian Fathers.

“Just as when a sunbeam falls on bright and transparent bodies, they themselves become brilliant too, and shed forth a fresh brightness from themselves, so souls wherein the Spirit dwells, illuminated by the Spirit, themselves become spiritual, and send forth their grace to others. Hence comes foreknowledge of the future, understanding of mysteries, apprehension of what is hidden, distribution of good gifts, the heavenly citizenship, a place in the chorus of angels, joy without end, abiding in God, the being made like to God, and, highest of all, the being made God. Such, then, to instance a few out of many, are the conceptions concerning the Holy Spirit, which we have been taught to hold concerning His greatness, His dignity, and His operations, by the oracles of the Spirit themselves.”

~ from: On the Holy Spirit (De Spiritu Sancto), Chap. 9

St. Gregory of Nazianzus: “… the confession of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost.”

Posted in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians, The Holy Trinity, Theology on April 6, 2023

St. Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 329 – 25 January 390), also known as Gregory the Theologian or Gregory Nazianzen, was a 4th-century Archbishop of Constantinople, theologian, and one of the Cappadocian Fathers (along with Basil the Great and Gregory of Nyssa). He is widely considered the most accomplished rhetorical stylist of the patristic age. Gregory made a significant impact on the shape of Trinitarian theology among both Greek and Latin-speaking theologians, and he is remembered as the “Trinitarian Theologian”.

“Besides all this and before all, keep I pray you the good deposit, by which I live and work, and which I desire to have as the companion of my departure; with which I endure all that is so distressful, and despise all delights; the confession of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost. This I commit unto you today; with this I will baptize you and make you grow. This I give you to share, and to defend all your life, the One Godhead and Power, found in the Three in Unity, and comprising the Three separately, not unequal, in substances or natures, neither increased nor diminished by superiorities or inferiorities; in every respect equal, in every respect the same; just as the beauty and the greatness of the heavens is one; the infinite conjunction of Three Infinite Ones, Each God when considered in Himself; as the Father so the Son, as the Son so the Holy Ghost; the Three One God when contemplated together; Each God because Consubstantial; One God because of the Monarchia. No sooner do I conceive of the One than I am illumined by the Splendour of the Three; no sooner do I distinguish Them than I am carried back to the One. When I think of any One of the Three I think of Him as the Whole, and my eyes are filled, and the greater part of what I am thinking of escapes me. I cannot grasp the greatness of That One so as to attribute a greater greatness to the Rest. When I contemplate the Three together, I see but one torch, and cannot divide or measure out the Undivided Light.”

~ from The Orations and Letters of Saint Gregory Nazianzus . Oration 40, XLI.

St. Maximus the Confessor: “…and having entered the dark cloud”

Posted in Contemplative Prayer (series), First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls on April 4, 2023

St. Maximus the Confessor (c. 580 – 662) was a 7th century Christian monk, theologian, and scholar who many contemporary scholars consider to be the greatest theologian of the Patristic era. Two of his most famous works are “Ambigua” – An exploration of difficult passages in the work of Pseudo-Dionysius and Gregory of Nazianzus, focusing on Christological issues, and “Questions to Thalassius” or “Ad Thalassium” – a lengthy exposition on various Scriptural texts. The following quote comes from Maximus’ “Two Hundred Chapters on Theology”, probably written after both Ambigua and Ad Thalassium, in about AD 633.

“The great Moses, having pitched his tent outside the camp, that is, having established his will and intellect outside visible realities, begins to worship God; and having entered the dark cloud [γνόφον], the formless and immaterial place of knowledge, he remains there, performing the holiest rites.

The dark cloud [γνόφος] is the formless, immaterial, and incorporeal condition containing the paradigmatic knowledge of beings; he who has come to be inside it, just like another Moses, understands invisible realities in a mortal nature; having depicted the beauty of the divine virtues in himself through this state, like a painting accurately rendering the representation of the archetypal beauty, he descends, offering himself to those willing to imitate virtue, and in this shows both love of humanity and freedom from envy of the grace of which he had partaken.”

~ from: Two Hundred Chapters on Theology, 1.84, 1.85.

The Chalcedonian Definition

Posted in Council of Chalcedon, Ekklesia and church on February 9, 2023

From: credomag.com/2021/02/the-chalcedonian-definition/

October 23, 2018

By Donald Fairbairn

Dr. Fairbairn is the Robert E. Cooley Professor of Early Christianity at Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary

The first thing one should notice from the title of this post is that the document produced at the Council of Chalcedon in October 451 was not a “creed”; it was a “definition.”

A creed, properly speaking, is not a statement of what Christians believe about our faith (That would be a “confession.”). Instead, a creed is a pledge of allegiance to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Creeds answer the question, “In whom do you believe?” more than the question “What do you believe?”

Creeds were originally intended for liturgical use, as the people of God affirmed their allegiance to the persons of the Trinity prior to baptism or the celebration of the Eucharist. In contrast, a definition is a commentary on a creed, designed to give more terminological precision to the content of that creed.

The Council of Chalcedon

At the Council of Chalcedon (the Fourth Ecumenical Council in the Greco-Roman world), the bishops who assembled were firmly convinced that the Nicene Creed was sufficient to affirm their faith in God, his Son, and his Spirit.

They were right: the Nicene Creed clearly identifies each of the divine persons, shows that they are equal to one another, and emphasizes that for us and for our salvation, the Son came down from heaven through the incarnation. At the same time, the bishops at Chalcedon were under intense pressure from the Emperor [Marcian] to produce a new creed, because he wanted to be able to call himself a new Constantine, presiding over the writing of a creed as Constantine had done at Nicaea in 325. The bishops also recognized that they needed more specificity than the Nicene Creed gave about how to understand Christ as both divine and human. As a result, they decided to write not a creed, but a “definition.”

Contrary to popular opinion, the Chalcedonian Definition is actually about five pages long— far too long to recite as part of a worship service. It includes the full text of two different version of the Nicene Creed: the original form from the First Ecumenical Council at Nicaea in 325, and the expanded version (the one familiar to us) from the Second Ecumenical Council at Constantinople in 381.

It includes descriptions of heresies that had arisen since 381 (Nestorianism—which regarded Christ not as God the Son incarnate but as a man inspired by God, and Eutychianism— which truncated the full humanity of the incarnate Son by refusing to accept his consubstantiality with us). Then the Definition concludes with a paragraph that gives specificity and terminological precision to the church’s articulation of the incarnate Christ. This paragraph is usually regarded mistakenly as being the entire definition, but with that mistake duly noted, it is still worth our while to read and consider that paragraph.

As I translate it, the paragraph reads as follows:

“Therefore, following the holy fathers, we all unite in teaching that we should confess one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ. This same one is perfect in deity, and the same one is perfect in humanity; the same one is true God and true man, comprising a rational soul and a body. He is of the same essence (homousios) as the Father according to his deity, and the same one is of the same essence (homousios) with us according to his humanity, like us in all things except sin. He was begotten before the ages from the Father according to his deity, but in the last days for us and our salvation, the same one was born of the Virgin Mary, the bearer of God (Theotokos), according to his humanity. He is one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, and Only Begotten, who is made known in two natures (physeis) united unconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably. The distinction between the natures (physeis) is not at all destroyed because of the union, but rather the property of each nature (physis) is preserved and concurs together into one person (prosopon) and subsistence (hypostasis). He is not separated or divided into two persons (prosopa), but he is one and the same Son, the Only Begotten, God the Logos, the Lord Jesus Christ. This is the way the prophets spoke of him from the beginning, and Jesus Christ himself instructed us, and the Council of the fathers has handed the faith down to us.”

Key Ideas

There are several things we should notice. First, even if one looks only at this paragraph rather than at the whole definition, it is obvious that it was not meant to be recited in church. It is written to teachers and leaders, indicating what we should teach about Christ. It is not a pledge of allegiance on the order of “we believe in one Lord Jesus Christ.” The Chalcedonian Definition seeks to affirm that the Son, who is fully equal to the Father, has genuinely become fully human without ceasing to be divine, in order to accomplish our salvation.

Second, this paragraph, like the definition as a whole, is a commentary on one line of the Nicene Creed, the line that asserts that for us and for our salvation, the Son came down from heaven and was incarnated. Accordingly, this paragraph insists in no uncertain terms that the man Jesus after the incarnation is the same person as the eternal Son of God before the incarnation. The phrases “the same one” and “one and the same” occur eight times in this brief paragraph. This personal continuity between the eternal Son and the man Jesus is essential: Jesus is not (as Nestorius believed) a man with a special connection to God. He is God the Son himself, who is now fully human because he has become incarnate.

Third, this paragraph provides much more specificity than the Nicene Creed about what it meant for the Son to come down through the incarnation. It uses the Greek word physis in the sense of “nature” (previously, many theologians had used that word differently), and thus it indicates that the incarnate Son is made known “in two natures” (deity and humanity). It uses two Greek words, prosopon and hypostasis, in the sense of “person,” and thus emphasizes that the Son is a single person—indeed, the same person before and after the incarnation.

Thus, the Chalcedonian Definition seeks to affirm that the Son, who is fully equal to the Father, has genuinely become fully human without ceasing to be divine, in order to accomplish our salvation.

Conclusion

Sadly, the definition proved to be tragically divisive, as many in the African and Asian churches misunderstood its use of the word physis and thought it was proclaiming the Son and Jesus as two different persons. But properly understood, the definition provides terminological precision for speaking theologically about the incarnation. It isn’t a creed and was never meant to be, but it helps the theologians—and the rest of us—understand what we mean when we say in the creed that the one who is “true God from true God” truly “came down from heaven and was incarnated and was made man.”

The Great Schism of 1054

Posted in Ekklesia and church on February 5, 2023

The early united Christian Church consisted of five co-equal Patriarchates: Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria. On July 16, 1054, Patriarch of Constantinople Michael Cerularius was excommunicated from the Christian church based in Rome, Italy. Cerularius’s excommunication was a breaking point in long-rising tensions between the Roman church based in Rome and the Byzantine church based in Constantinople (now Istanbul). The resulting split divided the European Christian church into two major branches: the Western Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. This split is known as the “Great Schism”, or the “Schism of 1054.”

The Great Schism came about due to a complex mix of religious disagreements and political conflicts festering within the church since the 8th century. From 756 to 857, the Roman papacy shifted from the orbit of the Byzantine Empire to that of the kings of the Franks. The period was characterized by “battles between Franks, Lombards and Romans for control of the Italian peninsula and of supreme authority within Christendom.”1

Some of the many religious disagreements between the western (Roman) and eastern (Byzantine) include:

- Disagreement over a unilateral Roman change to the Nicene Creed (of AD 325/381) adding the words “and the Son” (“filioque” in Latin), thus changing the ontological understanding of the Holy Spirit.

- Dispute whether or not it was acceptable to use unleavened bread for the sacrament of communion. (The west supported the practice, while the east did not.)

- Western belief that clerics should remain celibate.

Other than the dispute over the “filioque”, one can conclude that the remaining religious issues were mainly adiaphora, “indifferent things” that are neither right nor wrong, spiritually neutral things. Afterthoughts of man.

These religious disagreements were made worse by a variety of political conflicts, particularly regarding the power of Rome.

- Rome believed that the pope—the religious leader of the western Roman church—should have authority over the other four Christian Patriarchates— and thus have the religious authority over the eastern church and all of Christendom.

- Constantinople disagreed, pointing out that each of the five co-equal Patriarchates of the united church historically recognized their own leaders.

The western church eventually excommunicated Michael Cerularius and the entire eastern church. The eastern church retaliated by excommunicating the Roman pope Leo III and the Roman church with him.

The Schism became so politically charged that Western Latin Crusaders actually attacked and sacked the Eastern Byzantine capitol of Constantinople in 1204 during the corrupted Fourth Crusade. As with the religious disagreements, discussed above, these political conflicts were mainly adiaphora, “indifferent things”, that had little to no basis in spiritual matters. Afterthoughts of man.

This was the Great Schism of 1054.

1 Goodson, Caroline J. The Rome of Pope Paschal I: Papal Power, Urban Renovation, Church Rebuilding and Relic Translation, 817-824. Cambridge University Press. 2010

The Seven Ecumenical Councils

Posted in Council of Chalcedon, Ekklesia and church on February 3, 2023

A Church Council is an official ad hoc gathering of representatives to settle Church business. Such Councils are called rarely and are not the same as the regular gatherings of church leaders (synods, etc.). An ecumenical council is one at which the whole Church is represented. The three major contemporary branches of the Church (Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Protestant) recognize seven ecumenical councils: Nicea (325), Constantinople (381), Ephesus (431), Chalcedon (451), Constantinople II (553), Constantinople III (680), Nicaea II (787). Further ecumenical councils were rendered impossible by the widening split between Eastern Orthodox (Greek speaking) and Roman Catholic (Latin speaking) Churches, a split that was rendered official in AD 1054 and has not yet been healed.

Note: In addition to these universally-acknowledged councils, the Roman Catholic Church recognizes a further fourteen ecumenical councils: Constantinople IV (869-70), Lateran I (1123), Lateran II (1139), Lateran III (1179), Lateran IV (1215), Lyons I (1245), Lyons II (1274), Vienne (1311-12), Constance (1414-18), Florence (1438-45), Lateran V (1512-17), Trent (1545-63), Vatican I (1869-70), Vatican II (1965). But these were councils of only the Catholic Church, and are not recognized by the Orthodox or Protestant Churches.

The Council of Nicaea, 325

In 324 Constantine became sole ruler of the Roman Empire, reuniting an empire that had been split among rival rulers since the retirement of Domitian in 305. Constantine, the first Christian emperor, reunified the empire but found the Church bitterly divided over the nature of Jesus Christ. He wanted to reunify the Church as he had reunified the Empire. The major dispute was over the teaching of Arius, but there were other doctrinal issues also.

- Arianism: teaching of Arius of Alexandria (d. 335), who believed that Jesus Christ was created ex nihilo (out of nothing) by the Father to be the means of creation and redemption. Jesus was fully human, but not fully divine. He was elevated as a reward for his successful accomplishment of his mission. The Arian rallying cry was “There was a time when the Son was not.”

- Monarchianism: defended the unity (mono arche, “one source”) of God by denying that the Son and the Spirit were separate persons.

- Sabellianism: a form of monarchianism taught by Sabellias, that God revealed himself in three successive modes, as Father (creator), as Son (redeemer), as Spirit (sustainer). Hence there is only one person in the Godhead.

Constantine summoned the bishops at imperial expense to Nicea, 30 miles from his imperial capital in Nicomedia. Here they were to settle their differences in a council over which he presided. The council rejected Arianism. The Council issued a creed based upon an existing baptismal creed from Syria and Palestine. This creed became known as the Nicene Creed, or Confession of the Faith.

The Council also issued a set of canons, primarily dealing with church order.

The Council of Constantinople, 381

The second council met in Constantinople, the new imperial capital. The council issued a new creed, clarifying the understanding of the Holy Spirit as a co-equal Person of the Trinitarian Godhead as expressed in the Nicene Creed adopted in 325. This creed became known as the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed and remains the Confession of the Faith today in the Eastern Church.

Later, the Roman Church, under the influence of the Franks in the 8th century, unilaterally added a single word to the Creed, inserting Filioque “and the Son” to the statement about the Spirit, so as to read “the Spirit…proceeds from the Father and the Son.” In 867 the Patriarch of Constantinople declared Rome heretical for unilaterally inserting this clause into the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed. To this day the Western Church (Roman Catholic and Protestant) accepts the filioque clause, while the Eastern Church (Orthodox) does not.

The Council of Ephesus, 431

Condemned Nestorius and his teaching (Nestorianism) that Christ had two separable natures, human and divine. Declared Mary to be theotokos (lit. God-bearer, i.e., Mother of God) in order to strengthen the claim that Christ was fully divine.

The Council of Chalcedon, 451

Issued the Chalcedonian Formula, affirming that Christ is two natures in one person.

The Council of Constantinople II, 553

Condemned the Three Chapters, which emphasized Christ’s humanity at the expense of his deity. Their opponents held Alexandrian theology emphasizing Christ’s deity.

The Council of Constantinople III, 680

Condemned monothelitism (Christ has a single will), affirming that Christ had a human will and a divine will that functioned in perfect harmony.

The Council of Nicea II, 787

Declared that icons are acceptable aids to worship, rejecting the iconoclasts (icon-smashers)

Christian Heresies and Schisms in the First Five Centuries

Posted in Ekklesia and church on January 29, 2023

Below are some of the specific heresies in the first five centuries since Christ, and also the response of the Early Church Fathers. Ironically, much of Christian doctrine in the Early Church was developed to refute early heresies.

| Founder | Dates | Name of Movement | Type of Heresy |

| Simon Magus | 1st century | Gnostic | |

| Valentinus | 2nd century | Gnostic | |

| Marcion | c. 85-c. 160 A.D. | Gnostic | |

| Montanus | c. 156 A.D. | Schismatic | |

| Mani | 216 – 276 A.D. | Manichaeism | Gnostic |

| Donatus | c. 314 A.D. | Schismatic | |

| Arius | c. 250 – 336 A.D. | Arianism | Schismatic |

| Pelagius | died 418? A.D. | Pelagianism | Schismatic |

| Nestorius | died 440? A.D. | Nestorianism |

Simon Magus

Several of the Early Church Fathers, including Iranaeus, Hippolytus, and Justin Martyr believed that Christian Gnosticism started with Simon Magus (see Acts 8:9-24). The quote below is from Iranaeus’ Against Heresy:

“Simon the Samaritan was that magician of whom Luke, the disciple and follower of the apostles, [spoke]…Such was his procedure in the reign of Claudius Caesar, by whom also he is said to have been honored with a statue, on account of his magical power. This man, then, was glorified by many as if he were a God; and he taught that it was himself who appeared among the Jews as the Son…Now this Simon of Samaria, from whom all sorts of heresies derive their origin…” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies, Chapter 23)

Valentinian Gnosticism

“…Valentinus, who adapted the principles of the heresy called “Gnostic” to the peculiar character of his own school…” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies, Book 1, Chapter 11)

One of the most influential of the early “Christian” Gnostics was Valentinus (c. 137), who established schools in Egypt, Cyprus and Rome. His teachings were later spread by his student Ptolamaeus. According to Tertullian, Valentinus was denied the sought-after post of Bishop, and then turned against the established church:

“Valentinus had expected to become a bishop, because he was an able man both in genius and eloquence. Being indignant, however, that another obtained the dignity…he broke with the church of the true faith. Just like those (restless) spirits which, when roused by ambition, are usually inflamed with the desire of revenge, he applied himself with all his might to exterminate the truth; and finding the clue of a certain old opinion, he marked out a path for himself with the subtlety of a serpent. Ptolemaeus afterwards entered on the same path…” (Tertullian, Against the Valentinians)

It would be difficult to describe the complicated theology of Valentinus in a short space, so we will suffice to describe some of the main characteristics of his Gnostic views:

- The physical Universe was created on account of an error of Sophia (“Wisdom”). The Creator-God (the Old Testament God) created the evil material world.

- The Eternal Being produced emanations in the universe; as the distance between the emanations and the Eternal Being increased, knowledge of him lessened (this was to explain why evil could exist in the cosmos)

- The aim of Gnostics was to escape the bodily prison, and return to the Eternal Being (“The redemption of the inner spiritual man”)

- Christ the redeemer shows the way back to the Eternal Being (through gnosis)

- Jesus was pure spirit (Docetism). If matter is impure, God could not become incarnate.

- Valentinus believed that redemption is pre-ordained, and that only those towards the top of a hierarchy of mankind/cosmos would be redeemed:

- Pneumatics – the Gnostic initiates; the elect

- Psyche – ordinary church members, with no gnosis

- Choics – the majority of people with no hope of salvation

Marcion

“Marcion expressly and openly used the knife, not the pen, since he made such an excision of the Scriptures as suited his own subject-matter.” (Tertullian, Prescription Against Heretics”)

Marcion (c. 85 – c. 160 A.D.) was a Gnostic ship owner, who believed that there were two Gods in the universe (dualism) – the God depicted in the Old Testament, and the God represented by Jesus in the New Testament. He believed that the God of Goodness took pity on man and sent his Son to rescue him from the evil god. He believed also that Jesus was a spirit (docetism) and did not appear in the flesh. As such, he rejected the infancy narratives about Jesus, as well as the crucifixion and resurrection. On this topic, Tertullian wrote:

“…it was that Marcion actually chose to believe that He was a phantom, denying to Him the reality of a perfect body. Now, not even to His apostles was His nature ever a matter of deception. He was truly both seen and heard upon the mount; true and real was the draught of that wine at the marriage of (Cana in) Galilee; true and real also was the touch of the then believing Thomas…” (Tertullian, A Treatise on the Soul)

To accommodate these (and other) Gnostic beliefs, Marcion created a list of books that he considered authoritative. These included a condensed version of the Gospel of Luke (lacking the Nativity and Resurrection scenes), and 10 of Paul’s letters.

While the gnostic theology of Marcion was roundly condemned by the Early Church Fathers (such as Tertullian above), his list was the first known attempt at defining a New Testament canon, and it prodded the Early Church Fathers to give greater consideration to those books that should be considered authoritative.

Marcion was excommunicated in 144 A.D., and his sect died out by the end of the 3rd century. According to Tertullian, Marcion attempted to reconcile himself to the church before his death:

“Afterwards, it is true, Marcion professed repentance, and agreed to the conditions granted to him — that he should receive reconciliation if he restored to the church all the others whom he had been training for perdition: he was prevented, however, by death”. (Tertullian, The Prescription Against Heretics)

Response of the Church to 2nd Century Gnosticism

The response of the established church to early “Christian” Gnosticism was to solidify a creed, or basic statement of beliefs, that was in marked contrast to Gnostic beliefs. The resulting Apostles Creed came out of the 2nd century church, starting out as a baptismal liturgy, and eventually became the standard statement of Christian belief. In the chart below, notice the Gnostic ideas that are refuted by the Creed:

| Apostles Creed | Gnostic Idea Refuted |

| I believe in God the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth | ONE God, not two; God made material as well as heavenly things |

| Born of the virgin Mary | Jesus was NOT just a spirit |

| Suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead and buried | Christ was a real person, who existed in historical time |

| I believe…in the resurrection of the body | Material things are not innately evil (see also Gen 1:31) |

Also, in the aforementioned books written against heresy by Early Church Fathers such as Irenaeus, Tertullian, Justyn Martyr, etc., other key points were made that rejected heresy, such as:

- There was no hidden teaching in Christianity, or else the Apostles would have passed it on to their successors in the churches (Irenaeus himself was in a direct line of succession from John the Apostle, through St. Polycarp)

- The New Testament and Apostolic Tradition constitutes the faith of Christianity (Luther and Calvin would later disagree with the latter)

Montanist Heresy

Around c. 156 A.D., a self-styled prophet named Montanus started to attract followers in Phrygia, Asia Minor. Montanus wasn’t a heretic in the sense of the Gnostics, but he did preach a doctrine that conceivably could have been threatening to the established church. Among the characteristics of Montanism:

Like the followers of Peter Waldo and St. Francis in the Middle Ages, Montanus wanted a return to simpler church, as well as a more ascetic focus for believers (fasting, celibacy, separation from the world)

- Like the later Protestant Reformers, he questioned the authority of church hierarchy, and believed that the Word of God was the only true authority, revealed through the prophets

- He fostered a very charismatic environment, and believed that the Holy Spirit spoke directly through him, and his followers

So what was the problem, as far as the established church was concerned? The main issue seemed to be about the fact that the Montanists believed that they were receiving Divine Revelation, like the Old Testament prophets. Some of the bishops of the time (such as Serapion, bishop of Antioch) were concerned that such prophesizing might be viewed on the same level as Holy Scripture – and could interfere with people’s understanding of the core message of the Scriptures.

Around c. 190 A.D., Montanus was excommunicated, but his movement (which included Tertullian at one point) forced the established church to examine the role of the Holy Spirit in the contemporary church. In time, the response of church was that revelation ended with the Apostolic Age. Those with the gift of prophesy after the Apostolic Age were simply explaining the already existing Word of God – not adding to it.

The sect had pretty much died out by end of 4th century, although there is some evidence that it still existed in small pockets as late as the 8th century.

Origen: On the Borderline

Origen (185? – 254? A.D.), an Early Church Father, was Presbyter of Alexandria. And yet some of his theological views were condemned by Church councils (400, 543 A.D.), hundreds of years after his death. Among his views and/or his much later Origenist followers:

- Jesus is divine, but subordinate to the Father (John 14:28). (This view would later be mirrored by Arius in the 4th century, and lead to the creation of the Nicene Creed as a counter measure.) Because of this view, he thought that prayer should only be offered to the Father.

- Every human soul has existed eternally – and bodily existence is a result of pre-bodily sin

- All souls would ultimately be saved

Manichaeism

Manichaeism was one of the most influential Gnostic movements of the first several centuries A.D., and it survived well into the Middle Ages in one form or another. Its Persian founder Mani (216? – 276 A.D.) created a religion that was a curious blend of Gnosticism, Christianity, and the teachings of Persian Magi. Among the characteristics of Manichaeism:

- All religions are equally valid

- Dualist – two cosmic kingdoms, which included a Kingdom of Light (the Primal God) and the Kingdom of Darkness (Satan)

- Accepted as prophets: Adam, Noah, Abraham, Zoroaster, Buddha, Jesus, Paul, Mani

- Docetic – Christ was “a divine being clothed in the semblance of man”

- Had five grades or levels of believers (similar to the three of Valentius)

- Believed in cycles of life (reincarnation)

- Preached strict asceticism

The most famous convert to Manichaeism was St. Augustine, who repudiated Manichaeism in 384 A.D., and later stated:

“THROUGH the assisting mercy of God, the snares of the Manichaeans having been broken to pieces and left behind, having been restored at length to the bosom of the Catholic Church, I am disposed now at least to consider and to deplore my recent wretchedness. For there were many things that I ought to have done to prevent the seeds of the most true religion wholesomely implanted in me from boyhood, from being banished from my mind, having been uprooted by the error and fraud of false and deceitful men.” (St. Augustin, On Two Souls, Against the Manichaeans, translated by Albert H. Newman, D.D., Ll.D.)

There is some evidence that Manichaeism thought survived well into the Middle Ages, where it ran afoul of the Inquisition in the 13th century. The target of the Inquisition was a group of people known as Cathars (also known as the Albigensians), which comes from the Greek word katharoi, meaning pure.

The Cathars

Like their Gnostic forebears, the Cathars were dualists – they believed that there were two creator Gods – a pure God that created the heavens and things spiritual, and an Evil God that created all things physical and temporal. They generally associated the Evil God with the God of the Old Testament.

They were also docetists – they believed that Jesus was a spirit, not a flesh and blood human being. Thus, they rejected the doctrine of the death of Jesus on the cross, and His subsequent resurrection. They also seem to have adopted the views of the 4th century Presbyter of Alexandria Arius (see upcoming section) that stated that Jesus, while an exalted being, is not on the same level as the Father. The Cathars seem to have believed in reincarnation, as they viewed that the souls of men are trapped in evil physical bodies, and are released only after multiple iterations.

The Cathars were considered such a threat to the established church in the Middle Ages that both a Crusade and the Papal Inquisition were launched against them. The Albigensian Crusade (so named, because the French city of Albi was a Cathar stronghold) was launched against the Cathars in Southern France in 1209 by Pope Innocent III. The Crusade lasted for 20 years, and was marked by astonishing violence, the most famous example being on July 22, 1209, when the city of Beziers was sacked, with over 20,000 men, women and children killed by crusaders. Those Cathars that survived the Crusade were wiped out in the Papal Inquisition that followed in 1227, capped by the burning of 215 Cathar leaders at the Castle of Montsegur in 1244. The Cathars were, for all intents and purposes, extinct by the beginning of the 14th century.

Donatists

The roots of the Donatist schism date back to the 3rd century. In c. 250 A.D., Roman Emperor Decius ordered the persecution of Christians. As a result of this persecution, the Bishop of Rome Fabianus was murdered, and Church Father Origen was jailed. Many Christians (including some priests and bishops) committed apostasy – denying Christ to save themselves from persecution. After the persecutions ebbed in 251 A.D., the question was asked “Should priests that committed apostasy be allowed back into the church?”

Roman churchman Novatian (c. 200–258 A.D.) argued against admitting those that committed apostasy back into the church. After losing the election to fill the vacant position of Bishop of Rome in 251 A.D., Novatian and his followers split away from the Catholic Church. Among their views:

- Priests who had apostatized in the face of Roman persecution should not be allowed to dispense the sacraments

- Sacraments administered by the unworthy were invalid

- A holy church could not contain unholy members

By 254 A.D., however, when it was clear that Novatian was not receiving support from outside his circle of followers, many of the followers of Novatian had fled, or desired (re)entry into the Catholic Church. This led the established church to have to confront the issue of whether those that had been baptized by Novatianists could be accepted into the Catholic Church without being rebaptized.

A great debate was waged between Bishop (254-56 A.D.) Stephen of Rome and Cyprian of Carthage (c. 195–258 A.D.), who argued that baptisms given by schismatics were not real baptisms at all. Stephen, whose view ultimately prevailed noted that baptism belongs to Christ, not the church, and the standing of the baptizer is not the relevant issue.

A similar situation arose in the early fourth century. Emperor Diocletian had ordered the persecution of Christians throughout the empire (303 – 306 A.D.), and many Christians (including some bishops and priests) had committed apostasy. After Constantine came into power, the question of the mid-third century remained – what to do about those that had committed apostasy? The situation boiled over at Carthage in 311 A.D. when an archdeacon named Caecilianus was ordained by a bishop that was suspected of having committed apostasy during the Diocletian persecution. In retaliation, the Donatists set up a rival Bishop of Carthage (Majorinus in 311 A.D.; Donatus in 315 A.D.).

In time, the Donatists became a schismatic sect, claiming that they were the only true Christians. The Donatists refused to accept baptisms performed in the Catholic Church, claiming they were invalid. The Donatists also insisted that a baptism performed by an “impure” priest was not valid.

While Donatism was condemned at the Council of Arles in 314 A.D., it continued to flourish. Beginning in 393 A.D., St. Augustine, the great theologian of the early Catholic Church, turned his skills of eloquence and logic against the Donatists. Augustine argued (like Bishop Stephen before him) that baptism is of Christ, not of the baptizer. Therefore, “reformed” Donatists that wished to return to the Mother Church did not need to be rebaptized. Among Augustine’s many statements on the topic:

“It is true that Christ’s baptism is holy; and although it may exist among heretics or schismatics, yet it does not belong to the heresy or schism; and therefore even those who come from thence to the Catholic Church herself ought not to be baptized afresh.” (The Seven Books Of Augustin, Bishop Of Hippo, On Baptism, Against The Donatists, p. 780)

The Donatists were banished by emperor Honorius in 412 A.D., and completely disappeared by end of 7th century.

Arianism

The great theological debates of the 2nd century centered on exactly who Christ was, and what manner of being he was. In the early 4th century, the debate switched to what the relationship was between Christ and God the Father. Some church officials, such as a presbyter in Alexandria named Arius (c. 250 – 336 A.D.) argued that Jesus was divine, but on a lower level then the Father. Arius started with this premise:

“One God, alone unbegotten, alone everlasting, alone unbegun, alone true, alone having immortality, alone wise, alone good, alone sovereign.”

From this starting point, Arius ended up with the view that Christ was an intermediary distinct from the Father (or that there was a difference of substance (homoiousia), or essential being between the Father and the Son.)

On the other side of the issue was Athanasius, (c. 296-373 A.D.), later Bishop of Alexandria, who argued that the Word (John 1:1-18) became man – the Word did not come into a man. Thus, Christ is fully God and fully man.

High Noon occurred in 325 A.D. when Constantine, emperor of the Roman Empire ordered that the debate be settled once and for all. A great church council was ordered, and it took place at Nicea (in Bithynia). Arius lost the debate, and the view of Athanasius became the view of the church. The doctrine of homoousios was affirmed – that Christ was of one (or the same) substance with the Father. Out of the Council came the Nicene Creed – one of the two Creeds recognized by almost all of Christianity today. The original version (it was expanded in 381 A.D.) stated:

“We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of all things both visible and invisible; and in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the Son of God, Only begotten of the Father, that is to say, of the substance of the Father, God of God and Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made, both things in heaven and things on earth; who, for us men and for our salvation, came down and was made flesh, was made man, suffered, and rose again on the third day, went up into the heavens, and is to come again to judge both the quick and the dead; and in the Holy Ghost.” (emphasis added)

Arianism was perhaps the greatest threat to the Early Church out of all the schisms and heresies. By some estimates, almost half of all Christians were Arians at its peak in the 4th century. Although condemned by the Council of Nicea in 325 A.D., it didn’t die out completely until the 8th century. However, there are still groups today (such as the Unitarians) who, like Arius, reject Trinitarianism.

Pelagianism

Two more heresies/schisms would appear in the post-Nicene period – not everything was settled at the Council of Nicea. One of these heresies was promulgated by a monk named Pelagius.

Pelagius (c. 354 A.D. – after 418) was a British Monk who was horrified by the seeming lack of piety and purity practiced by Christians in Rome c. 380 A.D. He felt that the laxness of Roman Christians grew partly from the prevailing doctrine of Grace, which stated that humans on their own are incapable of purity, and can only be saved by God’s grace.

Pelagius and his followers (one student named Coelestius was especially influential) denied predestination, original sin, and the doctrine of Grace, maintaining the humans are not tainted by the sin of Adam and Eve, and that babies are born pure. As a result, humans have the free will to choose to live sinless lives. (In his somewhat confused theology, though, Pelagius still maintained that babies needed to be baptized.)

The main opponent to Pelagianism was St. Augustine of Hippo (who also combated the Donatists). Augustine wrote at least thirteen works and letters against Pelagius, and firmly entrenched in Catholic theology the doctrines of:

- Salvation through Grace

- Original Sin

- The necessity of baptism for salvation

- The damnation of unbaptized infants

Among Augustine’s writings about Pelagius:

“A NECESSITY arose which compelled me to write against the new heresy of Pelagius. Our previous opposition to it was confined to sermons and conversations, as occasion suggested, and according to our respective abilities and duties; but it had not yet assumed the shape of a controversy in writing. Certain questions were then submitted to me [by our brethren] at Carthage, to which I was to send them back answers in writings: I accordingly wrote first of all three books, under the title, “On the Merits and Forgiveness of Sins,” in which I mainly discussed the baptism of infants because of original sin, and the grace of God by which we are justified, that is, made righteous; but [I remarked] no man in this life can so keep the commandments which prescribe holiness of life, as to be beyond the necessity of using this prayer for his sins: “Forgive us our trespasses.” It is in direct opposition to these principles that they have devised their new heresy.” (St. Augustine, A Treatise On the Merits and Forgiveness Of Sins and On the Baptism Of Infants)

Pelagius was excommunicated in 418 A.D. Pelagianism was declared heretical at Council of Ephesus (431 A.D.).

Nestorianism

The final schism/heresy that we’ll examine in this study is Nestorianism. It was founded by two men – Theodoren (d. 428 A.D.; Bishop of Mopsuesta, 392 A.D.) and its namesake Nestorius (d. 440? A.D.; Patriarch of Constantinople, 428 A.D.). Among the arguments of Nestorianism:

There were two separate natures in Christ. Christ was a “Man who became God” rather than “God who became Man”. As such, Jesus of Nazareth and the Word were united.

- Therefore, Mary was not the “Mother of God”

- Tended to view Christ as a prophet and teacher, inspired by an indwelling logos

- Christ was the first “perfect man”

These viewpoints were declared heretical at Council of Ephesus (431 A.D.) and Council of Chalcedon (451 A.D.). The latter created a Creed which stated:

“We confess one and the same our Lord Jesus Christ, the same perfect in godhead, the same perfect in manhood, truly God and truly man, the same of rational soul and body.”

Nestorius himself was exiled to the Egyptian desert in 435 A.D., and Nestorianism diminished in popularity in the 5th century. However, there are still Nestorian churches in Iran and Iraq. And many Kurdistan Nestorians moved to San Francisco after World War I.