Posts Tagged christian mysticism

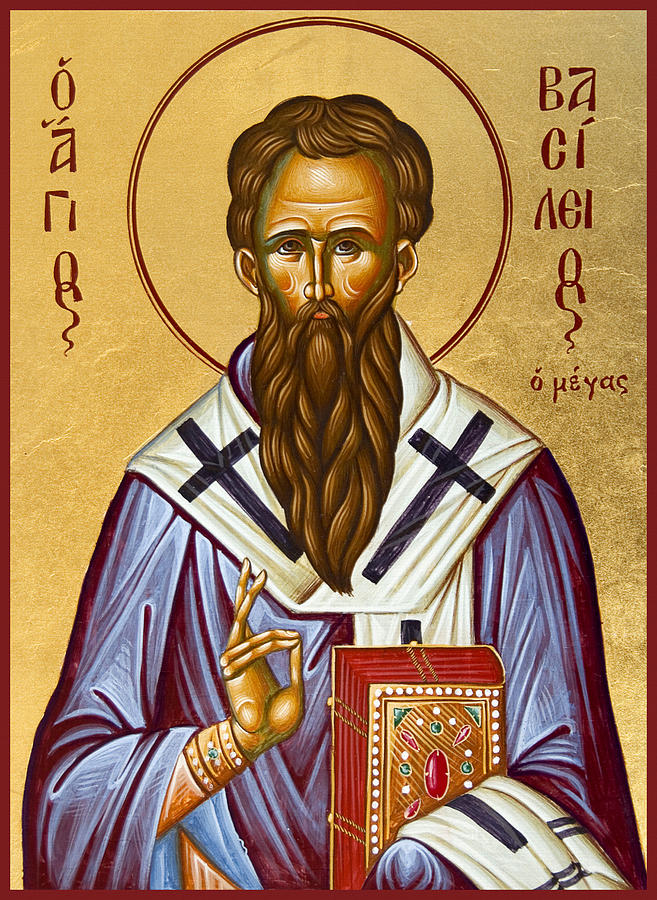

St. Basil the Great: “Homily About Ascesis – How a Monk Should be Adorned”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, Monasticism, Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians on April 8, 2023

St. Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great (330 – January 379), was a bishop of Caesarea Mazaca in Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey). He was an influential theologian who supported the Nicene Creed and opposed the heresies of the early Christian church. Together with Pachomius, he is remembered as a father of communal (coenobitic) monasticism in Eastern Christianity. Basil, together with his brother Gregory of Nyssa and his friend Gregory of Nazianzus, are collectively referred to as the Cappadocian Fathers.

“The monk, above all, must not possess anything in his life. He must have bodily isolation, proper clothing, a moderate tone of voice, and discipline speech; he must not cause a ruckus about the food and drink and he must eat in silence; he must be silent before his elders and be attentive to wiser men; he must love his peers and advise those junior in a loving way; he must move away from the immoral and the carnal and the sophisticated; he must think much and say less; he must not become impudent in his words, nor gossip and not be amenable to laughter; he must be adorned with shame, directing his gaze to the ground and his soul upward; he must not object with words of contention but rather be compliant; he must work with his hands and always keep in remembrance the end of this age; he must rejoice with hope, endure sadness, pray unceasingly and thank God for everything; he must be humble towards all and hate pride; he must be vigilant in keeping his heart pure of any evil thought; he must gather treasures in Heaven by keeping the commandments, examine himself for his thoughts and actions each day and not be involved in vain things of life and in idle talk; he must not examine inquisitively the life of idle people, but imitate the lives of the Holy Fathers; he must be happy with those who achieve virtue and not be envious; he must suffer with those suffering and weep with them and be sorry for them, but not criticise them; he must not reproach one who returns from his sin and never justify himself. Above all else he must confess before God and the men that he is a sinner and admonish the unruly, strengthen the faint-hearted, minister unto the sick and washed the feet of the saints; he must attend to hospitality and brotherly love, to be at peace with those who have the same faith and abhor the heretics; he must read the canonical books and not open even a single one of the occult; he must not talk about the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, but think and confess the uncreated and consubstantial Trinity with courage, and tell those who ask that there is the need of to be baptised, as we have received it from the tradition, to believe, as we have confessed it according to our baptism, and to glorify God, as we have believed.”

~ from: The Monastic Rule of St. Basil the Great

St. Gregory of Sinai: ‘Sowing in the Light’

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, Monasticism, Patristic Pearls on April 7, 2023

St. Gregory of Sinai (c. 1260s -1346) – was a well-travelled Greek Christian monk and writer from Smyrna (modern-day İzmir, Turkey). He was instrumental in the emergence of hesychasm on Mount Athos in the early 14th century. He was a contemporary of St. Gregory Palamas.

“According to St. Paul (cf. Rom. 15:16), you “minister” the Gospel only when, having yourself participated in the light of Christ, you can pass it on actively to others. Then you sow the Logos like a divine seed in the fields of your listeners’ souls. ‘Let your speech be always filled with grace’, says St Paul (Col. 4:6), ‘seasoned’ with divine goodness. Then it will impart grace to those who listen to you with faith. Elsewhere St. Paul, calling the teachers tillers and their pupils the field they till (cf. II Tim. 2:6), wisely presents the former as ploughers and sowers of the divine Logos and the latter as the fertile soil, yielding a rich crop of virtues. True ministry is not simply a celebration of sacred rites; it also involves participation in divine blessings and the communication of these blessings to others.”

~ from: The Philokalia

St. Macrina and the Healing of the Soldier’s Daughter

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians, Women in Early Christianity on April 6, 2023

St. Macrina the Younger (ca. AD 327 – July 379), was the older sister of three Cappadocian Saints and Bishops: Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Peter of Sebasteia. She was also friends with St. Gregory of Nanzianzus. Macrina transformed one of her family’s rural estates in Pontus (modern Turkey) into a monastery for ascetic virgins who came from both an aristocratic and non-aristocratic backgrounds. All members, including those from her own household, were free and ex-slaves received the same rights and obligations as their former masters. St. Basil established a men’s monastery nearby. Macrina was so well respected and loved by her younger brother, Gregory, that he wrote two books about her virtues, holiness, and intellect soon after her death in AD 379: The Life of Saint Macrina and On the Soul and the Resurrection. The post below is an excerpt from The Life of Saint Macrina, written in about AD 381.

“Along the way [from Macrina’s funeral], a distinguished military man who had command of a garrison in a little town of the district of Pontus, called Sebastopolis, and who lived there with his subordinates, came with the kindly intentions to meet me [Gregory of Nyssa] when I arrived there. He had heard of our misfortune [the death of Macrina] and he took it badly (for, in fact, he was related to our family by kinship and also by close friendship). He gave me an account of a miracle worked by Macrina; and this will be the last event I shall record in my story before concluding my narrative. When we stopped weeping and were standing in conversation, he said to me, “Hear what a great good has departed from human life.” And with this he stated his story.

“It happened that my wife and I once desired to visit that powerhouse of virtue; for that’s what I think that place should be called in which the blessed soul spent her life. Our little daughter was also with us and she suffered from an eye ailment as a result of an infectious disease. And it was a hideous and pitiful sight, since the membrane around the pupil was swollen and because of the disease had taken on a whitish tinge. As we entered that divine place, we separated, my wife and I, to make our visit to those who lived a life of philosophy1 therein, I going to the monks’ enclosure where your brother, Peter [of Sebaste], was abbot, and my wife entering the convent to be with the holy one. After a suitable interval had passed, we decided it was time to leave the monastery retreat and we were already getting ready to go when the same, friendly invitation came to us from both quarters. Your brother asked me to stay and take part in the philosophic table, and the blessed Macrina would not permit my wife to leave, but she held our little daughter in her arms and said that she would not give her back until she had given them a meal and offered them the wealth of philosophy; and, as you might have expected, she kissed the little girl and was putting her lips to the girl’s eyes, when she noticed the infection around the pupil and said, “If you do me the favor of sharing our table with us, I will give you in return a reward to match your courtesy.” The little girl’s mother asked what it might be and the great Macrina replied, “It is an ointment I have that has the power to heal the eye infection.” When after this a message reached me from the women’s quarters telling me of Macrina’s promise, we gladly stayed, counting of little consequence the necessity which pressed us to make our way back home.

Finally the feasting was over and our souls were full. The great Peter with his own hands had entertained and cheered us royally, and the holy Macrina took leave of my wife with every courtesy one could wish for. And so, bright and joyful, we started back home along the same road, each of us telling the other what happened to each as we went along. And I recounted all I had seen and heard in the men’s enclosure, while she told me every little thing in detail, like a history book, and thought that she should omit nothing, not even the least significant details. On she went telling me about everything in order, as if in a narrative, and when she came to the part where a promise of a cure for the eye had been made, she interrupted the narrative to exclaim, “What’s the matter with us! How did we forget the promise she made us, the special eye ointment?” And I was angry about our negligence and summoned some one to run back quickly to ask for the medicine, when our baby, who was in her nurse’s arms, looked, as it happened, towards her mother. And the mother gazed intently at the child’s eyes and then loudly exclaimed with joy and surprise, “Stop being angry at our negligence! Look! There’s nothing missing of what she promised us, but the true medicine with which she heals diseases, the healing which comes from prayer, she has given us and it has already done its work, there’s nothing whatsoever left of the eye disease, all healed by that divine medicine!” And as she was saying this, she picked the child up in her arms and put her down in mine. And then I too understood the incredible miracles of the gospel, which I had not believed in, and exclaimed: “What a great thing it is when the hand of God restores sight to the blind, when today his servant heals such sicknesses by her faith in Him, an event no less impressive than those miracles!” All the while he was saying this, his voice was choked with emotion and the tears flowed into his story. This then is what I heard from the soldier.”

~ from The Life of Saint Macrina, by St. Gregory of Nyssa

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Philosophy as the ideal of the Christian monastic life plays a central role in The Life of Saint Macrina (LSM) and will undoubtedly seem strange, even alien, to modern ears long accustomed to the scholasticism and secularization of academic disciplines. However, the essential and organic unity of the spiritual, intellectual, and physical ways of life, central to the monastic Rule of St. Basil, even yields such a remarkable phrase in the LSM as “the philosophic table”. This usage accurately reflects St. Gregory’s fourth-century Christian understanding of “philosophy”, i.e., love of wisdom, passion for the truth, care of the soul, contemplation (theoria), and ascetic physical discipline which spurns attachment to material things while recognizing that the body will be restored to its true God-created stature by the resurrection.

St. Basil the Great: “On the Holy Spirit”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Monasticism, Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians, The Holy Trinity, Theology on April 6, 2023

St. Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great (330 – January 379), was a bishop of Caesarea Mazaca in Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey). He was an influential theologian who supported the Nicene Creed and opposed the heresies of the early Christian church. Together with Pachomius, he is remembered as a father of communal (coenobitic) monasticism in Eastern Christianity. Basil, together with his brother Gregory of Nyssa and his friend Gregory of Nazianzus, are collectively referred to as the Cappadocian Fathers.

“Just as when a sunbeam falls on bright and transparent bodies, they themselves become brilliant too, and shed forth a fresh brightness from themselves, so souls wherein the Spirit dwells, illuminated by the Spirit, themselves become spiritual, and send forth their grace to others. Hence comes foreknowledge of the future, understanding of mysteries, apprehension of what is hidden, distribution of good gifts, the heavenly citizenship, a place in the chorus of angels, joy without end, abiding in God, the being made like to God, and, highest of all, the being made God. Such, then, to instance a few out of many, are the conceptions concerning the Holy Spirit, which we have been taught to hold concerning His greatness, His dignity, and His operations, by the oracles of the Spirit themselves.”

~ from: On the Holy Spirit (De Spiritu Sancto), Chap. 9

St. Maximus the Confessor: “…and having entered the dark cloud”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Contemplative Prayer (series), First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls on April 4, 2023

St. Maximus the Confessor (c. 580 – 662) was a 7th century Christian monk, theologian, and scholar who many contemporary scholars consider to be the greatest theologian of the Patristic era. Two of his most famous works are “Ambigua” – An exploration of difficult passages in the work of Pseudo-Dionysius and Gregory of Nazianzus, focusing on Christological issues, and “Questions to Thalassius” or “Ad Thalassium” – a lengthy exposition on various Scriptural texts. The following quote comes from Maximus’ “Two Hundred Chapters on Theology”, probably written after both Ambigua and Ad Thalassium, in about AD 633.

“The great Moses, having pitched his tent outside the camp, that is, having established his will and intellect outside visible realities, begins to worship God; and having entered the dark cloud [γνόφον], the formless and immaterial place of knowledge, he remains there, performing the holiest rites.

The dark cloud [γνόφος] is the formless, immaterial, and incorporeal condition containing the paradigmatic knowledge of beings; he who has come to be inside it, just like another Moses, understands invisible realities in a mortal nature; having depicted the beauty of the divine virtues in himself through this state, like a painting accurately rendering the representation of the archetypal beauty, he descends, offering himself to those willing to imitate virtue, and in this shows both love of humanity and freedom from envy of the grace of which he had partaken.”

~ from: Two Hundred Chapters on Theology, 1.84, 1.85.

Rohr: “The Cosmic Christ”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in New Nuggets on October 30, 2022

Fr. Richard Rohr – is a Franciscan priest, Christian mystic, and teacher of Ancient Christian Contemplative Prayer. He is the founding Director of the Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, NM.

“There were clear statements in the New Testament giving a cosmic meaning to Christ (Colossians 1, Ephesians 1, John 1, 1 John 1, and Hebrews 1:1-4), and the schools of Paul and John were initially overwhelmed by the hope contained in this message. In the early Christian era, a few Eastern Fathers (such as Origen of Alexandria, Gregory of Nyssa, and Maximus the Confessor) noticed that the Christ was clearly something older, larger, and different than Jesus himself. They mystically saw that Jesus is the union of human and divine in one person, and the Christ is the eternal union of matter and Spirit from the beginning of time. But the later centuries tended to lose this mystical element in favor of a more dualistic Christianity. We were all the losers. What we could not unite in Jesus, we could not unite in ourselves!

Christianity became another moralistic religion (which loved to be on top). It was overwhelmingly aligned with a very limited period of history (empire building through war) and a small piece of the planet (Europe), not the whole earth or any glorious destiny (Romans 8:18ff) for us all. Not surprisingly, many Christians ended up tragically fighting evolution—along with most early human rights struggles (such as women’s suffrage, rights for those on the margins, racism, classism, homophobia, earth care, and slavery)—because we had no evolutionary notion of Christ who was forever “groaning in one great act of giving birth” (Romans 8:22). Until the reforms of the 1960’s and the Second Vatican Council, Roman Catholic Christianity was overwhelmingly a tribal religion and hardly “catholic” at all.

We should have been at the forefront of all of these love and justice issues. The Christian religion was made-to-order—to grease the wheels of human consciousness toward love, nonviolence, justice, inclusivity, love of creation, and the universality of such a message. Mature religion serves as a conveyor belt for the evolution of human consciousness. Immature religion actually stalls people at very early stages of magical, mythic, and tribal consciousness, while they are convinced they are enlightened or “saved.” This is more a part of the problem than any kind of solution. Only the non-dual and mystical mind gets you all the way through.

Authentic mystical experience connects us and keeps connecting us at ever-newer levels, breadths, and depths, “until God is all in all” (1 Corinthians 15:28). Or as Paul also writes earlier in the same letter, “the world, life and death, the present and the future are all your servants, for you belong to Christ, and Christ belongs to God” (1 Corinthians 3:22-23). Full salvation is finally universal belonging and universal connecting. Our word for that is ‘heaven’.“

Universal Connection, Meditation, Friday, March 27, 2015

What it Means to be Human – East and West – 2

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Christian Anthropology -East & West (Series) on February 13, 2022

Eastern Greek Anthropology

Human beings are dignified creatures created by God. This very positive view of humanity was the position of all early Christian authorities and remained the conviction of the unified Church for nearly five centuries. The doctrine included the following points from Genesis 1:26:

- God created humankind intentionally. Humans are not an accident of evolution.

- God created humans in his image and likeness.

This means that humanity is theomorphic, having the form, image, or likeness of God. This is a very optimistic and positive view of anthropology.

Some of the Greek Fathers made a distinction between image (Heb. צֶ֫לֶם – tselem; Grk. εικονα –eikona) and likeness (Heb. דְּמוּת – demuth; Grk. ομοιωσιν – homoiosin) in Gen 1:26. They argued that image and likeness were not synonymous or rhetorical equivalents. They pointed out that in Hebrew, image (tselem) always indicates a “physical” or structural image of some kind. This distinguishes it from likeness (demuth), which usually refers to some kind of “functional” image, to be like, or resemble. I bring this up to point out that later Western Latin theologians would attempt to refute the distinction between image and likeness, calling it a simple example of rhetorical Hebrew parallelism or hendiadys.

To illustrate the Eastern Greek understanding, I quote St. Basil the Great (c. 330-c. 379), who said this about God’s image and likeness:

“Let us make the human being [he quotes God] according to our image and according to our likeness”. [Then he continues] By our creation, we have the first, and by our free choice we build the second. In our initial structure co-originates and exists our coming into being according to the image of God. By free choice, we are conformed to that which is according to the likeness of God.

Note also in this quote, Basil also alludes to two other very important early doctrines; “free choice” (free will) and “conformed… to the likeness” (synergy). We will encounter both of these doctrines further on.

This made human beings inherently valuable and dignified. This was the theological position of the early Church Fathers such as Sts. Basil and Ephraim in the East and St. Ambrose in the West.

For many Fathers, the metaphor of the Tree of Life served as a symbol and expression of humankind’s communion with God, participating in the very life of God in paradise.

But humankind was expelled from paradise when it freely chose to live without God, when it chose death over life in God. This is the “Fall”, the primordial sin.

So, expelled from paradise and stripped of his dignity, humankind suffered what St. Athanasius (c. 298— 373) described as an anthropological catastrophe. It disrupted and disfigured the intention of God for the human race. Athanasius wrote, “Because death and corruption were gaining ever firmer hold on them, the human race was in the process of destruction.” He termed this the “De-humanization of man”. Humanity suffered and waited for God to act.

God did respond and he responded positively through the Incarnation of his Son, the Logos, the Christ, to defeat sin and clearly teach humanity the path of salvation, to a restoration of a life in God. John the theologian describes it in John 1:14, “the Logos became flesh and tabernacles among us”. Through Christ man is re-created. In a famous passage from his book, “On the Incarnation”, Athanasius echoes the words of St. Irenaeus and other Fathers before (and after) him:

“God became man that man might become god.”

In other words, the early church Fathers declared that the deification of humanity was possible. This is a very, very positive affirmation of the dignity, value, and potential of every human being.

The Fathers of the Eastern Greek Church described salvation in many different ways. There was more than just one image of salvation, but one of the most common, compelling, and powerful was that of the forementioned deification (Grk, theosis), or union with God.

The role of baptism was vitally important to the early church in the process of salvation of man through deification. It was not just for the forgiveness of sins that baptism imparted, but also for the impartation of deification and the experience of paradise, bringing a person into the light of God himself. St. Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 313-386) explains:

Great indeed is the baptism which is offered you. It is a ransom to captives, the remission of offenses, the death of sin, the regeneration of the soul, the garment of light, the holy seal indissoluable, the chariot to heaven, the luxury of paradise, a procuring of the kingdom, and the gift of adoption.

St, Cyril also talks about the rite of chrismation, the impartation of the gift of the Holy Spirit. That distinct rite always followed baptism immediately. Effectively there was no separation of the two rites in terms of time. This is a further indication that baptism is not just for the remission of sins but also a gift of life in the kingdom of heaven; the opportunity for deification.

Again, we are presented with a very positive view of the human person.

There is another doctrine critical to an understanding of salvation as the deification of humanity: the understanding of the essence and energies of God. Appropriated from Aristotelian metaphysics by the early Greek Fathers, this doctrine states that God in his essence is simply unknowable to humanity, so great and so far beyond human comprehension that he will never be knowable. However, God, through his actions and activity in creation, shares his energies with human beings made in his image and likeness to know him and participate in his life.

Basil tells us:

While we affirm that we know our God in his energies, we scarcely promise that he may be approached in his very essence. For although his energies descend to us, his essence remains inaccessible.

As a result of this doctrine of divine essence and energies the Greek Fathers described how humans could experience the immanent presence and life of an otherwise transcendent and unknowable God: deification.

Yet again, a very positive, optimistic view of humanity.

There are two more doctrines which complete the Eastern Greek understanding of anthropology; Free will and Synergy. Humans possess free will (not to be confused with autonomy) and can exercise it in a way as synergy, or cooperation, with the energies God. So, human beings are assigned a great dignity as they participate with God in their own salvation, even if in an asymmetrical way (God initiates everything!). Part of this synergy requires a deep desire on the part of the believer for a purification (katharsis) that leads to an experience of God (theoria), and ultimately union with God (theosis).

St. Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335-c.395), brother of St. Basil, sums it up beautifully:

The Lord does not say that it is blessed to know something theoretically about God, but to possess God in oneself.

This demonstrates that the Greek East maintained a very positive view of the inherent dignity and value of humanity, a very optimistic anthropology.

Again, I must emphasize that this positive, optimistic anthropology was the prevailing position of the united universal Christian Church for the first 400 years of its existence. In fact, it remains the doctrine of the Eastern Orthodox Church to this day, including all five of the original Patriarchates of the united Church, with the notable exception of Rome.

We will deal with the anthropology of the Latin West, next.

What it Means to be Human – East and West – 3

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Christian Anthropology -East & West (Series) on February 13, 2022

Western Latin Anthropology

We now examine the Latin West and the foundation of an alternative anthropology, which became increasingly pessimistic about the human condition. This pessimism would grow to have a profound impact upon the Middle Ages and lead to the large-scale abandonment of traditional Christianity during the Renaissance.

The foundation of this pessimistic anthropology is based on the early 5th century thought of St. Augustine (354-430), Bishop of Hippo Regius, in the Roman Province of Numidia on the North African coast (modern north-east Algeria).

Augustine outweighs, by far, the collective influence of all the other Latin Fathers (e.g., St. Jerome, St. Ambrose, Gregory the Great) and dominates the theological thinking and tradition of Western Latin Christianity from the 5th century all the way up to the present. By Western Latin Christianity I include the Roman Catholic Church and the vast majority of the 35,000+ denominations contained within Protestantism. As we shall see, the Protestant Reformer John Calvin will make much use of Augustine’s thought.

Augustine’s own life experiences, detailed in his book Confessions, and his disputes with British-born heretic Pelagius (c. 354- c.418) and his disciples did much to influence his thinking on the human will and grace.

Pelagius believed that humans are self-willed and autonomous in relationship to God. He even had a slogan for this belief: A deo emancipatus homo est. Man is emancipated from God.

How different this is from the Greek patristic understanding of human free will in synergy with God and totally dependent on God, finding fulfillment only in divine life.

But Augustine engaged Pelagius very differently. He took the opposite view of the human will from Pelagius, developing a doctrine of heteronomy; being ruled by another than oneself. Augustine believed that humans possess a free will, but that it has been vitiated, that is weakened and undermined and functionally powerless. Based on that conclusion, Augustine came up with his own slogan: non posse non peccare. [Man is] not able not to sin.

Not a very optimistic or positive view of humanity.

Therefore, to Augustine, salvation comes to depend on divine intervention in the form of a grace from God that precedes any action from a human being toward good; it came to be known as prevenient grace. It is prevenient grace that causes the human will to do good. Augustine saw this grace as created, and not God himself. How different this is from the Greek patristic doctrine of grace as the uncreated energies that really are God and penetrate and deify the believer and bring them ever more fully within the life of God himself.

To Augustine, if the human will is good, then it is through God and his prevenient grace activating the will. Of course, according to Augustine’s doctrine of heteronomy, there is the other (hetero) that could activate the human will as well. That would be the will of the devil. But in either case, it’s not the human will, but the will of another that leads the human in the direction he takes in life.

As a corollary, Augustine also developed the doctrine of “predestination”, which declares that, given that the human will as vitiated and powerless, God predestines those whom he has chosen as elect to save.

Again, not a very optimistic or positive assessment of the human will.

Augustine’s doctrine of predestination goes further than anything discussed to this point in undermining a belief that humans possess a free will and that they can work out their salvation in cooperation, or synergy, with God.

More than 1,100 years later, Protestant Reformer John Calvin would double-down and fully develop Augustine’s doctrine of predestination. If you believe that Augustine’s influence was limited to the Roman Catholic church and did not effect Protestant theology, I invite you to consider Calvin’s T.U.L.I.P., a summary of his principle doctrines; Total depravity, Unconditional election, Limited atonement, Irresistible grace, and Perseverance of the saints. Calvin drew directly from Augustine and is perhaps the most consistent theologian under his influence during the 16th century Protestant Reformation in the West. The Protestant Reformation bought Augustinian theology, pretty much in whole or at least in part.

Augustine, while rightly defending Orthodoxy against the anthropological heresy of Pelagius, had unfortunately taken positions that put him at odds with the consensus of the early unified church, East and West, concerning the condition of humanity, its inherent value and dignity, its place in this age, and the possibility of experiencing the divine, paradise itself, even in this world.

The last of Augustine’s unique doctrines we will discuss is arguably his most controversial; original sin. This doctrine goes well beyond the conception of the Fall and primordial sin of Adam and Eve that had been developed by Eastern Greek Fathers and even by Western Latin Fathers before the 5th century. For Augustine, the Fall resulted in humankind’s actual participation in the guilt of Adam’s original sin. This is a fundamental difference between the Eastern Greek patristic understanding of the Fall and the subsequent Western Latin Augustinian understanding.

This gets a little tedious but stay with me.

Augustine was led to this interpretation of the Fall by the translation of the Bible that was now being used in the West in his time. In the fourth century, St. Jerome translated the Bible into Latin (the Latin Vulgate bible), and in a very important passage from the epistle of Paul to the Romans 5:12, the original Greek was mistranslated by Jerome. Scholar David Bentley Hart, author of the recent The New Testament, a Translation, remarks that this “notoriously defective rendering in the Latin Vulgate (in quo omnes peccaverunt) constitutes one of the most consequential mistranslations in Christian history.” Below is the original Greek of Romans 5:12 (underline mine):

Διὰ τοῦτο ὥσπερ δι’ ἑνὸς ἀνθρώπου ἡ ἁμαρτία εἰς τὸν κόσμον εἰσῆλθεν καὶ διὰ τῆς ἁμαρτίας ὁ θάνατος, καὶ οὕτως εἰς πάντας ἀνθρώπους ὁ θάνατος διῆλθεν ἐφ’ ᾧ πάντες ἥμαρτον

The key here is that in the original Greek, above, the word “ἐφ’ ᾧ” (transliterated as “ef ho”), underlined near the end of the passage, is usually translated as “because” in English, as you can clearly see, underlined in the New King James Version (NKJ) translation, below:

Therefore, just as through one man [Adam] sin entered the world and death through sin, and thus death spread to all men because all sinned…

So, “Death and sin entered the world and spread to all human beings because all sinned.”

But in the Latin Vulgate, Jerome mistranslated “ef ho” and entirely changed the meaning of Romans 5:12. Jerome’s Latin translation of “ef ho” was “in quo”, which means “in whom”, and relates, in this passage, to Adam himself. This would mean that entire human race itself participated in Adam’s sin, in a willful act of transgression.

Augustine’s poor skills in Greek would not allow him to read the original Greek New Testament, so he was forced to rely solely on Jerome’s Latin Vulgate.

So, with this flawed translation of Romans 5:12 in hand, Augustine was able to assert that in Adam, in the person of Adam and in his very act of willful rebellion against God in the Fall, in the original sin, all human beings have sinned; all human beings have willfully participated, as descendants of Adam, in Adam’s personal sin.

Adam’s sin, for Augustine, was grounded in his concept of concupiscence, or evil desire. As a result, all of Adam’s descendants (all of humanity) participated in that act of will and are personally guilty for the transgression. His inclination toward this interpretation of the Fall came from his doctrine of grace and free will, that he had worked out early in his life in response to his personal experiences with lustful desires (cf. Confessions) and from his response to the earlier Pelagian controversy (both earlier in this summary).

It goes without saying that this reflects a negative, pessimistic view of humanity.

Augustine’s doctrine of original sin had important corollaries that were worked out in the Western Latin church over time. Some of these corollaries were worked out by Augustine himself. For example:

1. One corollary states that: if all human beings have sinned in Adam through original sin and been conceived in sin and have therefore come into the world personally guilty of original sin, then all human beings are deserving of punishment by God. The human condition is understood as one deserving of punishment, universal punishment.

2. Another corollary that grew out of Augustine’s doctrine of original sin was that unbaptized infants who died before they could be baptized were destined for hell because they were born with the guilt of Adam and, not having that guilt washed away by baptism, were destined to be punished in hell for it.

3. Yet another corollary to the doctrine of original sin is that baptism increasingly becomes understood as a sacrament exclusively of washing away, of remission of sins. Baptism lost its earlier traditional aspect of also imparting deification, the gift of the Holy Spirit deifying the believer.

4. Finally, a corollary to Augustine’s doctrine of original sin is that humanity became characterized by the condition of depravity: a moral bankruptcy. Augustine used the term massa damnata, a damned mass, for the entire human race awaiting punishment were it not for the life-creating sacraments of the Church.

Augustine’s anthropological pessimism saw the human condition in the world as one of misery, almost unmitigated misery. Salvation was seen as a release from punishment in the afterlife.

As Augustine reflected on these miseries, which result from the reality of original sin, he also discussed the role of punishment and the value of punishment, arguing that punishment can, and often does, play a valuable role in bringing the saints who have been predestined for paradise to that experience which awaits them after their death.

So, paradise, from which humanity was expelled, has no place in this world. It is something predestined saints will experience after death in this world. This life is penal, a place of punishment. But that punishment is good, purificatory, for the numbered elect saints being prepared for paradise.

For everybody else, it’s just punishment.

A very negative and pessimistic anthropology, indeed.

The Philokalia of the Neptic Fathers

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, Monasticism, Patristic Pearls on October 23, 2017

The Philokalia (Ancient Greek: φιλοκαλία “love of the beautiful, the good) is “a collection of texts written between the 4th and 14th centuries by spiritual masters” of the Eastern Orthodox Church mystical hesychast tradition. They were originally written for the guidance and instruction of monks in “the practice of the contemplative life.” The publishers of the current English translation state that “the Philokalia has exercised an influence far greater than that of any book other than the Bible in the recent history of the Orthodox Church.”

The Philokalia is the foundational text of hesychasm (“quietness”), the inner spiritual tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church dating back to the Desert Fathers of the 4th century. Hesychastic practices include contemplative prayer; quiet sitting, inner stillness, and repetitive recitation of the Jesus Prayer. While traditionally taught and practiced in monasteries, hesychasm teachings have spread over the years to include laymen.

The availability of an English translation of the Philokalia is relatively very recent:

- From 1957-1963 the Third Greek edition of the Philokalia was published in Athens in five volumes. The English translation is based on this edition.

- From 1979-1995 the first English translation of the first four of the five volumes (Third Greek edition) of the Philokalia was made by Kallistos Ware, G. E. H. Palmer, and Philip Sherrard, and published.

- In 2023 the first English translation of the fifth, and final, volume of the Philokalia was made by Kallistos Ware, G. E. H. Palmer, and Philip Sherrard, and published.

Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware), one of the editors of the current English translation, believes that the Philokalia is a:

“Book for all Christians

In the year 1782 a massive folio volume was published in Greek at the city of Venice, bearing the title Φιλοκαλία τῶν Ἱερῶν Νηπτικῶν, Philiokalia of the Holy Neptic Fathers. At the time of its first appearance this book seems to have had only a limited impact upon the Greek Orthodox world, while in the West it remained for a long time totally

“Philokalia”, Current English Translation

unknown. Yet in retrospect it is clear that the Philokalia was one of the most significant Greek books to be published during the whole period of the four centuries of the Turcocratia; indeed, arguably it was the most significant and influential of all. Today, after two centuries, it is still in print, both in the original Patristic Greek and in a modern Greek version; and it is available in translation, not only in most of the languages used in countries that are traditionally Orthodox, but also in virtually all the languages of Western Europe. Alike in the original and in translation, it has been regularly reprinted in the past forty years, and in Britain and the United States, not to mention other countries, the sales are increasing every year. In many circles, non-Orthodox as well as Orthodox, it has become customary to speak of a characteristically ‘Philokalic’ approach to theology and prayer, and many regard this ‘Philokalic’ standpoint as the most creative element in contemporary Orthodoxy.

There are some books which seem to have been composed not so much for their own age as for subsequent generations. Little noticed at the time of their initial publication, they only attain their full influence two or more centuries afterwards. The Philokalia is precisely such a work.

What kind of a book is the Philokalia? In the original edition of 1782, there is a final page in Italian: this is a licenza, a permission to publish, issued by the Roman Catholic censors at the University of Padua. In this they state that the volume contains nothing ‘contrary to the Holy Catholic Faith’ (contro la Santa Fede Cattolica), and nothing ‘contrary to good principles and practices’ (contro principi, e buoni costumi). But, though bearing a Roman Catholic imprimatur, the Philokalia is in fact entirely an Orthodox book. Of the thirty-six different authors whose writings it contains -dating from the fourth to the fifteenth century- all are Greek, apart from one, who wrote in Latin, St. John Cassian (d. circa 430) or ‘Cassian the Roman’ as he is styled in the Philokalia; and this exception is more apparent than real, for Cassian grew up in the Christian East and received his teaching from Evagrios of Pontus, the disciple of the Cappadocian Fathers.

Who are the editors of the Philokalia? The 1782 title page bears in large letters the name of the benefactor who financed the publication of the book: … διὰ δαπάνης τοῦ Τιμιωτάτου, καὶ Θεοσεβεστάτου Κυρίου Ἰωάννου Μαυρογορδάτου (this is perhaps the John Mavrogordato who was Prince of Moldavia during 1743 – 47). But neither on the title page nor anywhere in the 1.206 pages of the original edition are the names of the editors mentioned. There is in fact no doubt about their identity: they are St. Makarios of Corinth (1731-1805) and St. Nikodimos the Hagiorite (1749-1809), who were both associated with the group known collectively as the Kollyvades.

What was the purpose of St. Makarios and St. Nikodimos in issuing this vast collection of Patristic texts on prayer and the spiritual life? The second half of the eighteenth century constitutes a crucial turning-point in Greek cultural history. Even though the Byzantine Empire fell in 1453, it can justly be claimed that the Byzantine -or, more exactly, the Romaic- period of Orthodox history continued uninterrupted until the late eighteenth century. The Church, that is to say, continued to play a central role in the life of the people; despite Western influences, whether Roman Catholic or Protestant, theology continued to be carried out in a spirit that was basically Patristic, and most Greeks, when looking back to the past, took as their ideal the Christian Empire of Byzantium.

During the later decades of the eighteenth century, however, a new spirit began to prevail among educated Greeks, the spirit of modern Hellenism. This was more secular in its outlook than was Romaic culture, although -initially, at any rate- it was not explicitly anti-religious. Its protagonists looked back, beyond the Byzantine period, to ancient Greece, taking as their ideal the Athens of Pericles that was so greatly admired in the West, and their models were not the Greek Fathers but the authors of the classical period. These exponents of modern Hellenism were inspired, however, not simply by the Western reverence for classical studies, but more broadly by the mentality of the Enlightenment (Aufklärung), by the principles of Voltaire and the French Encyclopedists, by the ideologists of the French Revolution (which began only seven years after the publication of the Philokalia), and by the pseudo-mysticism of Freemasonry.

Needless to say, we are not to imagine that at the end of the eighteenth century there was a simple transition, with the Romaic tradition drawing abruptly to an end, and being totally replaced by the outlook of Neohellenism. On the contrary, the Romaic standpoint has continued to coexist, side by side with Neohellenism, in nineteenth and twentieth century Greece. The two approaches overlap, and there has always been – and still exists today – a subtle and complex interaction between the two. Alexander Solzenitsyn remarks in The Gulag Archipelago that the line of demarcation separating good and evil runs through the middle of every human heart. By the same token it can be said that the line of demarcation between the Romaios and the Hellene runs through the middle of the heart of each one of us.

If Adamantios Korais is the outstanding representative of modern Hellenism at the end of the eighteenth century, then the outstanding spokesmen of the Romaic or traditional Orthodox spirit during the same epoch are the editors of the Philokalia, St. Nikodimos and St. Makarios. They and the other Kollyvades were profoundly disturbed by the growing infiltration of the ideas of the Western Aufklärung among their fellow-countrymen. They believed that the regeneration of the Greek Church and nation could come about only through a recovery of the neptic and mystical theology of the Fathers ‘Do not set your hope in the new secularism of the West; that will prove nothing but a deceit and a disappointment’, they said in effect to their fellow-Greeks. ‘Our only true hope of renewal is to rediscover our authentic root in the Patristic and Byzantine past’. Is not their message as timely today as ever it was in the eighteenth century?

The Kollyvades proposed, therefore, a far-reaching and radical programme of ressourcement, a return to the authentic sources of Orthodox Christianity. This programme had three primary features. First, the Kollyvades insisted, in the field of worship, upon a faithful observance of the Orthodox liturgical tradition. Among other things, they urged that memorial services should be celebrated on the correct day,

“Philokalia”, Greek Edition

Saturday (not Sunday); hence the sobriquet ‘Kollyvades’. But this was far from being their main liturgical concern. Much more important was their firm and unwavering advocacy of frequent communion; this proved to be highly controversial, and brought upon them persecution and exile. Secondly, they sought to bring about in theology a Patristic renaissance; and in this connection they undertook an ambitious programme of publications, in which the Philokalia played a central role. Thirdly, within the Patristic heritage, they emphasized above all else the teachings of Hesychasm, as represented in particular by St. Symeon the New Theologian in the eleventh century and by St. Gregory Palamas in the fourteenth. It is precisely this Hesychast tradition that forms the living heart of the Philokalia, and that gives to its varied contents a single unity.

Such, then, is the cultural context of the Philokalia. It forms part -a fundamental and primary part- of the Patristic ressourcement that the Kollyvades sought to promote. The Kollyvades looked upon the Fathers, not simply as an archeological relic from the distant past, but as a living guide for contemporary Christians. They therefore hoped that the Philokalia would not gather dust on the shelves of scholars, but that it would alter people’s lives. They meant it to have a supremely practical purpose.

In this connection it is significant that St. Nicodimos and St. Makarios intended the Philokalia to be a book not just for monks but for the laity, not just for specialists but for all Christians. The book is intended, so its title page explicitly states, ‘for the general benefit of the Orthodox’ (εἰς κοινὴν τῶν Ὀρθοδόξων ὠφέλειαν). It is true that virtually all the texts included were written by monks, with a monastic readership in mind. It is also true that, with the exception of seven short pieces at the end of the volume, the material is given in the original Patristic Greek, and is not translated into the Demotic, even though St. Nikodimos and St. Makarios used the Demotic in most of their other publications. Nevertheless, despite the linguistic difficulties in many Philokalic texts, more especially in the writings of St. Maximos the Confessor and St. Gregory Palamas, the editors leave no doubt concerning their purpose and their hopes. In his preface St. Nikodimos affirms unambiguously that the book is addressed ‘to all of you who share the Orthodox calling, laity and monks alike’. In particular, St. Nikodimos maintains, the Pauline injunction, ‘Pray without ceasing’ (1 Thessalonians 5:17), is intended not just for hermits in caves and on mountain-tops but for married Christians with responsibilities for a family, for farmers, merchants and lawyers, even for ‘kings and courtiers living in palaces’. It is a universal command. The best belongs to everyone.

St. Nikodimos recognized that, in thus making Hesychast texts available to the general reader, he was exposing himself to possible misunderstanding and criticism. Thus he writes in the preface:

Here someone might object that it is not right to publish certain of the texts included in this volume, since they will sound strange to the ears of most people, and may even prove harmful to them.

Indeed, is there not a risk that, if these texts are made readily accessible for all to read in a printed edition, certain people may go astray because they lack personal guidance from an experienced spiritual father? This was an objection to which St. Nikodimos’ contemporary, St. Paisius Velichkovsky (1722-94), was keenly sensitive. For a long time he would not allow his Slavonic translation of the Philokalia to appear in print, precisely because he feared that the book might fall into the wrong hands; and it was only under pressure from Metropolitan Gabriel of St. Petersburg that he eventually agreed to its publication. St. Makarios and St. Nikodimos were in full agreement with St. Paisius about the immense importance of obedience to a spiritual father. But at the same time they were prepared to take the risk of printing the Philokalia. Even if a few people go astray because of their conceit and pride, says St. Nikodimos, yet many will derive deep benefit, provided that they read the Philokalic texts ‘with all humility and in a spirit of mourning’. If we lack a geronta, then let us trust to the Holy Spirit; for in the last resort He is the one true spiritual guide.”

~ Met. Kallistos (Ware) from “The Inner Unity of the Philokalia and its Influence in East and West”

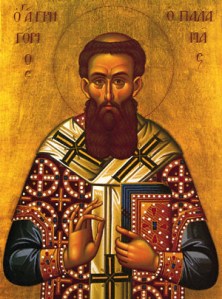

St. Gregory Palamas: “Theosis, the Uncreated Thaboric Light”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, Monasticism, Patristic Pearls, Theology on October 21, 2017

St. Gregory Palamas (Greek: Γρηγόριος Παλαμάς; 1296–1359) – was a monk of Mount Athos in Greece and later the archbishop of Thessaloniki, known as a preeminent theologian of Hesychasm. The teachings embodied in his writings defending Hesychasm against the attack of Barlaam are sometimes referred to as Palamism, and his followers as Palamites.

“Since the Son of God, in his incomparable love for man, did not only unite His divine Hypostasis with our nature, by clothing Himself in a living body and a soul gifted with intelligence… but also united himself… with the human hypostases themselves, in mingling himself with each of the faithful by communion with his Holy Body, and since he becomes one single body with us (cf. Eph. 3:6), and makes us a temple of the undivided Divinity, for in the very body of Christ dwelleth the fullness of the Godhead bodily (Col. 2:9), how should he not illuminate those who commune worthily with the divine ray of His Body which is within us, lightening their souls, as He illumined the very bodies of the disciples on Mount Thabor? For, on the day of the Transfiguration, that Body, source of the light of grace, was not yet united with our bodies, it illuminated from outside those who worthily approached it, and sent the illumination into the soul by an intermediary of the physical eyes; but now, since it mingled with us and exists in us, it illuminates the soul from within.”

~ from: Triads I.iii.38.