Dallas Wolf

Hesychastic hermit

Homepage: https://firstthoughtsofgod.com

Women Leaders in the 1st Century Apostolic Church

Posted in Ekklesia and church, Women in Early Christianity on March 20, 2025

“There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male or female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.” Galatians 3:28

| Woman | Reference | Comment |

| Phoebe | Romans 16:1-2 | “a deacon [minister] of the church” |

| Priscilla (or Prisca) | Rom 16:3-5, 1 Cor 16:19 | Founded at least two home churches with Aquila |

| Junia | Rom 16:7 | “prominent among the apostles” |

| Nympha | Col 4:15 | Started church in her house |

| Lydia | Acts 16:14, 15, 40 | Started church in her house |

| Apphia | Philem 2 | House church in her home |

| Mary, Mother of Jesus | Acts 1:14 | Present at first meetings of church |

| Euodia, Syntyche | Phil 4:2-3 | “for they have struggled beside me in the work of the gospel” |

| Four daughters of Philip | Acts 21:8/9 | Prophetesses |

Full Scripture References:

- “I commend to you our sister Phoebe, a deacon [minister] of the church at Cenchreae,…” Romans 16:1

- “Greet Prisca and Aquila, who work with me in Christ Jesus…” Romans 16:3

- “Aquila and Prisca, together with the church in their house, greet you warmly in the Lord.” 1 Corinthians 16:19

- “Greet Andronicus and Junia, my relatives who were in prison with me; they are prominent among the apostles, and they were in Christ before I was.” Romans 16:7

- “Give my greetings to the brothers and sisters in Laodicea, and to Nympha and the church in her house.” Colossians 4:15

- “A certain woman named Lydia, a worshiper of God, was listening to us; she was from the city of Thyatira and a dealer in purple cloth. The Lord opened her heart to listen eagerly to what was said by Paul. When she and her household were baptized , she urged us, saying, “If you have judged me to be faithful in the Lord, come and stay at my home.” And she prevailed upon us.” Acts 16:14, 15

- “After leaving the prison they went to Lydia’s home, and when they had seen and encouraged the brothers and sisters there, they departed.” Acts 16:40

- “… to Apphia our sister, to Archippus our fellow soldier, and to the church in your house.” Philem 2

- “All these were constantly devoting themselves to prayer, together with certain women, including Mary the mother of Jesus, as well as his brothers.” Acts 1:14

- “I urge Euodia and I urge Syntyche to be of one mind in the Lord. Yes, and I ask you also, my loyal companion, help these women, for they have struggled beside me in the work of the gospel,…” Philippians 4:2, 3

- “The next day we left and came to Caesarea; and we went into the house of Philip the evangelist, one of the seven, and stayed with him. He had four unmarried daughters who had the gift of prophecy.” Acts 21:8, 9

Note: Other women mentioned include Julia, Mary, the mother of Rufus, Nereus’ sister, Persis, Tryphaena, and Tryphosa, but we know nothing more about them.

The Acts of Paul and Thecla: A Pauline Tradition Linked to Women

Posted in Women in Early Christianity on March 20, 2025

Nancy A. Carter has an M.Div. from Union Theological Seminary in New York City, where she won the Hitchcock Award in Church History. Her Ph.D. is in literary studies (literature and theology) from American University in Washington, D.C. She has authored books for church laity including Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew: Who Do You Say That I Am?, a spiritual growth study for United Methodist Women written with Bishop Leontine T. C. Kelly.

Women, Paul and Early Christianity

The The Life of the Great Martyr Thecla of Iconium, Equal to the Apostles, as recorded in the apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla is part of a Pauline tradition that provided apostolic blessing for women’s leadership roles in the church. Although the events related in the Acts are legendary, a real Thecla may have lived in Asia Minor. Like many stories about Jesus and the Apostles, originally her tales were told orally. The content of the book, with its wealth of women characters, most of whom support each other (including a lioness who protects Thecla!), suggests Thecla’s adventures were popular in women’s circles.

An orthodox Christian, probably from Asia Minor, penned the Acts of Thecla between 160-190. The book circulated in several languages, including Greek, Coptic, Ethiopic, and Armenian. The Syrian and Armenian churches included the Acts of Thecla in their early biblical canons. It is now a part of the Christian apocrypha.

The extant manuscripts reflect masculine editing that probably de-emphasized Paul’s support of women’s leadership. No longer present are references to Thecla’s baptizing others, which were most likely in the earliest stories. Even so, the Acts of Thecla includes a story about Thecla baptizing herself with Paul’s blessing! Later Paul commissions her to return to her home town Iconium to teach and evangelize.

A Women’s Tradition

Although Thecla’s adventures were popular, particularly in Asia Minor, the stories angered some of the church’s best known opponents to women’s leadership. The African church father Tertullian (160-230) complained that some Christians were using the example of Thecla to legitimate women’s roles of teaching and baptizing in the church (On Baptism 17).

The controversy among different Christian groups about women’s roles is reflected in the Bible. For example, 1 Timothy 4:7 warned, “Have nothing to do with profane myths and old wives tales.” Quite possibly “old wives tales” alludes to stories told by women that supported female leadership roles.

By the turn of the first century, the landscape and expectations of the church had changed. Paul and other church leaders had believed that the end of the world was coming soon, in their lifetime. For this reason, certain institutions, such as marriage, were de-emphasized in order to prepare for the Christ’s return. Christians were preparing for a different kind of “marriage”– to the Heavenly Bridegroom. Now Christian leadership realized that the time of Jesus’ return could not be known and that they needed to approach life differently.

The Pastoral Epistles, I & II Timothy and Titus, rejected ascetic values like those embodied by Thecla and the women prophets in Corinth. I Timothy (100 -110 C.E.) proclaimed that teachings which forbade marriage and demanded abstinence from certain foods came from “deceitful spirits and doctrines of demons” (4:1-3). In the Acts of Paul, those who became Christian also chose chastity. Paul and Thecla were vegetarians and teetotalers, perhaps because of a cultural belief that meat and alcohol inflamed sexual passion. The author of I Timothy instructed, “No longer drink only water, but take a little wine for the sake of your stomach and your frequent ailments” (5:23).

In the second century, the women’s ascetic movement had become too strong for the taste some of the male leadership. In stark contrast to the letters of Paul, I Timothy declared that women would not be saved by living chaste lives but rather through bearing children (2:15). Paul had proposed in his first letter to the Corinthians (7:9) that it was better to marry than “burn” (“be aflame with passion,” NRSV); he preferred but did not insist that Christians choose sexual continence. Calvin Roetzel observes that “in spite of Paul’s preference for celibacy as a divine gift (I Cor. 7:7), scholars have paid surprisingly little attention to this historical datum of the apostle’s life.”

Both the Pastoral Epistles and the Acts of Paul and Thecla drew upon material in Paul’s letters and other sources. In reality, Paul certainly did not teach that women must birth children in order to be saved; neither did he insist that women remain virgins or cease sexual activity in marriage in order to be saved. “The only passages in the Acts of Thecla which explicitly condemn marriage (the Encratite heresy) are 2:16 and 4:2, and it will be noted that the speaker is not Paul himself but his accuser attributing this view to the Apostle” [Pachomius Library Notes]. In this instance, the noncanonical writing is truer to Paul’s teaching than the canonical one.

The Power of Thecla and Her Story in the Early Church

Without a doubt, Thecla and Paul were key symbols for the ideals of early Christian ascetic movements, especially in Egypt, Syria, and Armenia. Obviously the women’s ascetic movement did not end, even though the Pastoral Epistles declared women’s salvation was bearing children. Christian ascetic practices by both men and women continue to this day.

The power of Thecla’s story spread throughout early Christianity. Following are just a few illustrations. Several early church fathers from both the East and West praised Thecla as a model of feminine chastity. She became “venerated from the shores of the Caspian almost to the shores of the Atlantic. In the fourth century a church in Antioch of Syria was dedicated to Thecla. Another church in Eschamiadzin, Iberia, from the fifth century has a wall design showing Paul preaching to her. In Egypt [are several examples of art]. In Rome, scholars found a sarcophagus graced by a relief portraying Paul and Thecla traveling together in a boat.” At least three places claim her burial place: Meryemlik [Ayatekla], Turkey; Maalula, Syria; and Rome, Italy.

Tradition says that Thecla traveled with Paul to Spain. Another apocryphal Acts which mentions Thecla is the Acts of Xanthippe, Polyxena, and Rebecca (c. 270). Some women in Spain hear Paul’s preaching and leave their husbands to follow him.

In the Modern Church

Called “Equal to the Apostles,” Thecla is especially revered in the Eastern church. In Maalula, Syria, the Greek Orthodox monastery of St. Thecla, built near a cave said to be the martyr’s, the nuns and novices continue in her tradition, which included care of orphans and assisting those who were poor. Santa Tecla (Spanish for “Saint Thecla”) is the patron saint of Tarragona, Spain.

In the early 1980s, interest in the Acts of Thecla revived in Christian scholarship, particularly though not exclusively among women scholars. Whereas Thecla’s virginity was her most praised aspect by early church fathers such as Methodius (c. 300), some modern writings emphasize how sexual continence provided a means for early Christian women take leadership in the church.

In modern times, virginity is viewed as a conservative value but, in early Christianity, abstention from sex empowered women in new ways. They became the “feminists” of their day, no longer participating in the traditional hierarchy of the household where the patriarch was in charge and woman’s primary role was childbearing. For example, one way the ascetic women prophets in Corinth celebrated their new life in Christ was through ecstatic prayer and prophesy. In Christ there was no male or female; all were of equal status.

Today the figure of Thecla is seen as reflecting primarily traditional values that the post-apostolic church encouraged in women, including prayer and contemplation, but also challenging opposition to women’s leadership in other aspects of early Christian life. For example, Margaret Y. MacDonald says, “Even if Thecla’s life is purely fictional, it remains significant that in second-century Pauline circles, a woman could be depicted as a teacher and evangelist in her own right…. Moreover, her story sheds light on how women who chose to remain unmarried or who dissolved engagements and marriages to unbelievers may have contributed to growing hostility between early Christian groups and Greco-Roman society.” Gail Corrington Streete observes that some women in the Christian apocryphal literature are given “a place in the line of apostolic authority” in that they exercise leadership even when male apostles are not present, such as Thecla. She, with Paul’s blessing, baptized herself and was commissioned as a missionary in her own right.”

Women In Ancient Christianity: The New Discoveries

Posted in Women in Early Christianity on March 20, 2025

Karen L. King is Professor of New Testament Studies and the History of Ancient Christianity at Harvard University in the Divinity School. She has published widely in the areas of Gnosticism, ancient Christianity, and Women’s Studies. Here she examines the evidence concerning women’s important place in early Christianity. She draws a surprising new portrait of Mary Magdalene and outlines the stories of previously unknown early Christian women.

In the last twenty years, the history of women in ancient Christianity has been almost completely revised. As women historians entered the field in record numbers, they brought with them new questions, developed new methods, and sought for evidence of women’s presence in neglected texts and exciting new findings. For example, only a few names of women were widely known: Mary, the mother of Jesus; Mary Magdalene, his disciple and the first witness to the resurrection; Mary and Martha, the sisters who offered him hospitality in Bethany. Now we are learning more of the many women who contributed to the formation of Christianity in its earliest years.

Perhaps most surprising, however, is that the stories of women we thought we knew well are changing in dramatic ways. Chief among these is Mary Magdalene, a woman infamous in Western Christianity as an adulteress and repentant whore. Discoveries of new texts from the dry sands of Egypt, along with sharpened critical insight, have now proven that this portrait of Mary is entirely inaccurate. She was indeed an influential figure, but as a prominent disciple and leader of one wing of the early Christian movement that promoted women’s leadership.

Certainly, the New Testament Gospels, written toward the last quarter of the first century CE, acknowledge that women were among Jesus’ earliest followers. From the beginning, Jewish women disciples, including Mary Magdalene, Joanna, and Susanna, had accompanied Jesus during his ministry and supported him out of their private means (Luke 8:1-3). He spoke to women both in public and private, and indeed he learned from them. According to one story, an unnamed Gentile woman taught Jesus that the ministry of God is not limited to particular groups and persons, but belongs to all who have faith (Mark 7:24-30; Matthew 15:21-28). A Jewish woman honored him with the extraordinary hospitality of washing his feet with perfume. Jesus was a frequent visitor at the home of Mary and Martha, and was in the habit of teaching and eating meals with women as well as men. When Jesus was arrested, women remained firm, even when his male disciples are said to have fled, and they accompanied him to the foot of the cross. It was women who were reported as the first witnesses to the resurrection, chief among them again Mary Magdalene. Although the details of these gospel stories may be questioned, in general they reflect the prominent historical roles women played in Jesus’ ministry as disciples.

WOMEN IN THE FIRST CENTURY OF CHRISTIANITY

After the death of Jesus, women continued to play prominent roles in the early movement. Some scholars have even suggested that the majority of Christians in the first century may have been women.

The letters of Paul – dated to the middle of the first century CE – and his casual greetings to acquaintances offer fascinating and solid information about many Jewish and Gentile women who were prominent in the movement. His letters provide vivid clues about the kind of activities in which women engaged more generally. He greets Prisca, Junia, Julia, and Nereus’ sister, who worked and traveled as missionaries in pairs with their husbands or brothers (Romans 16:3, 7, 15). He tells us that Prisca and her husband risked their lives to save his. He praises Junia as a prominent apostle, who had been imprisoned for her labor. Mary and Persis are commended for their hard work (Romans 16:6, 12). Euodia and Syntyche are called his fellow-workers in the gospel (Philippians 4:2-3). Here is clear evidence of women apostles active in the earliest work of spreading the Christian message.

Paul’s letters also offer some important glimpses into the inner workings of ancient Christian churches. These groups did not own church buildings but met in homes, no doubt due in part to the fact that Christianity was not legal in the Roman world of its day and in part because of the enormous expense to such fledgling societies. Such homes were a domain in which women played key roles. It is not surprising then to see women taking leadership roles in house churches. Paul tells of women who were the leaders of such house churches (Apphia in Philemon 2; Prisca in I Corinthians 16:19). This practice is confirmed by other texts that also mention women who headed churches in their homes, such as Lydia of Thyatira (Acts 16:15) and Nympha of Laodicea (Colossians 4:15). Women held offices and played significant roles in group worship. Paul, for example, greets a deacon named Phoebe (Romans 16:1) and assumes that women are praying and prophesying during worship (I Corinthians 11). As prophets, women’s roles would have included not only ecstatic public speech, but preaching, teaching, leading prayer, and perhaps even performing the eucharist meal. (A later first century work, called the Didache, assumes that this duty fell regularly to Christian prophets.)

MARY MAGDALENE: A TRUER PORTRAIT

Later texts support these early portraits of women, both in exemplifying their prominence and confirming their leadership roles (Acts 17:4, 12). Certainly the most prominent among these in the ancient church was Mary Magdalene. A series of spectacular 19th and 20th century discoveries of Christian texts in Egypt dating to the second and third century have yielded a treasury of new information. It was already known from the New Testament gospels that Mary was a Jewish woman who followed Jesus of Nazareth. Apparently of independent means, she accompanied Jesus during his ministry and supported him out of her own resources (Mark 15:40-41; Matthew 27:55-56; Luke 8:1-3; John 19:25).

Although other information about her is more fantastic, she is repeatedly portrayed as a visionary and leader of the early movement.( Mark 16:1-9; Matthew 28:1-10; Luke24:1-10; John 20:1, 11-18; Gospel of Peter ). In the Gospel of John, the risen Jesus gives her special teaching and commissions her as an apostle to the apostles to bring them the good news. She obeys and is thus the first to announce the resurrection and to play the role of an apostle, although the term is not specifically used of her. Later tradition, however, will herald her as “the apostle to the apostles.” The strength of this literary tradition makes it possible to suggest that historically Mary was a prophetic visionary and leader within one sector of the early Christian movement after the death of Jesus.

The newly discovered Egyptian writings elaborate this portrait of Mary as a favored disciple. Her role as “apostle to the apostles” is frequently explored, especially in considering her faith in contrast to that of the male disciples who refuse to believe her testimony. She is most often portrayed in texts that claim to record dialogues of Jesus with his disciples, both before and after the resurrection. In the Dialogue of the Savior, for example, Mary is named along with Judas (Thomas) and Matthew in the course of an extended dialogue with Jesus. During the discussion, Mary addresses several questions to the Savior as a representative of the disciples as a group. She thus appears as a prominent member of the disciple group and is the only woman named. Moreover, in response to a particularly insightful question, the Lord says of her, “´You make clear the abundance of the revealer!'” (140.17-19). At another point, after Mary has spoken, the narrator states, “She uttered this as a woman who had understood completely”(139.11-13). These affirmations make it clear that Mary is to be counted among the disciples who fully comprehended the Lord’s teaching (142.11-13).

In another text, the Sophia of Jesus Christ, Mary also plays a clear role among those whom Jesus teaches. She is one of the seven women and twelve men gathered to hear the Savior after the resurrection, but before his ascension. Of these only five are named and speak, including Mary. At the end of his discourse, he tells them, “I have given you authority over all things as children of light,” and they go forth in joy to preach the gospel. Here again Mary is included among those special disciples to whom Jesus entrusted his most elevated teaching, and she takes a role in the preaching of the gospel.

In the Gospel of Philip, Mary Magdalene is mentioned as one of three Marys “who always walked with the Lord” and as his companion (59.6-11). The work also says that Lord loved her more than all the disciples, and used to kiss her often (63.34-36). The importance of this portrayal is that yet again the work affirms the special relationship of Mary Magdalene to Jesus based on her spiritual perfection.

In the Pistis Sophia, Mary again is preeminent among the disciples, especially in the first three of the four books. She asks more questions than all the rest of the disciples together, and the Savior acknowledges that: “Your heart is directed to the Kingdom of Heaven more than all your brothers” (26:17-20). Indeed, Mary steps in when the other disciples are despairing in order to intercede for them to the Savior (218:10-219:2). Her complete spiritual comprehension is repeatedly stressed.

She is, however, most prominent in the early second century Gospel of Mary, which is ascribed pseudonymously to her. More than any other early Christian text, the Gospel of Mary presents an unflinchingly favorable portrait of Mary Magdalene as a woman leader among the disciples. The Lord himself says she is blessed for not wavering when he appears to her in a vision. When all the other disciples are weeping and frightened, she alone remains steadfast in her faith because she has grasped and appropriated the salvation offered in Jesus’ teachings. Mary models the ideal disciple: she steps into the role of the Savior at his departure, comforts, and instructs the other disciples. Peter asks her to tell any words of the Savior which she might know but that the other disciples have not heard. His request acknowledges that Mary was preeminent among women in Jesus’ esteem, and the question itself suggests that Jesus gave her private instruction. Mary agrees and gives an account of “secret” teaching she received from the Lord in a vision. The vision is given in the form of a dialogue between the Lord and Mary; it is an extensive account that takes up seven out of the eighteen pages of the work. At the conclusion of the work, Levi confirms that indeed the Saviour loved her more than the rest of the disciples (18.14-15). While her teachings do not go unchallenged, in the end the Gospel of Mary affirms both the truth of her teachings and her authority to teach the male disciples. She is portrayed as a prophetic visionary and as a leader among the disciples.

OTHER CHRISTIAN WOMEN

Other women appear in later literature as well. One of the most famous woman apostles was Thecla, a virgin-martyr converted by Paul. She cut her hair, donned men’s clothing, and took up the duties of a missionary apostle. Threatened with rape, prostitution, and twice put in the ring as a martyr, she persevered in her faith and her chastity. Her lively and somewhat fabulous story is recorded in the second century Acts of Thecla. From very early, an order of women who were widows served formal roles of ministry in some churches (I Timothy 5:9-10). The most numerous clear cases of women’s leadership, however, are offered by prophets: Mary Magdalene, the Corinthian women, Philip’s daughters, Ammia of Philadelphia, Philumene, the visionary martyr Perpetua, Maximilla, Priscilla (Prisca), and Quintilla. There were many others whose names are lost to us. The African church father Tertullian, for example, describes an unnamed woman prophet in his congregation who not only had ecstatic visions during church services, but who also served as a counselor and healer (On the Soul 9.4). A remarkable collection of oracles from another unnamed woman prophet was discovered in Egypt in 1945. She speaks in the first person as the feminine voice of God: Thunder, Perfect Mind. The prophets Prisca and Quintilla inspired a Christian movement in second century Asia Minor (called the New Prophecy or Montanism) that spread around the Mediterranean and lasted for at least four centuries. Their oracles were collected and published, including the account of a vision in which Christ appeared to the prophet in the form of a woman and “put wisdom” in her (Epiphanius, Panarion 49.1). Montanist Christians ordained women as presbyters and bishops, and women held the title of prophet. The third century African bishop Cyprian also tells of an ecstatic woman prophet from Asia Minor who celebrated the eucharist and performed baptisms (Epistle 74.10). In the early second century, the Roman governor Pliny tells of two slave women he tortured who were deacons (Letter to Trajan 10.96). Other women were ordained as priests in fifth century Italy and Sicily (Gelasius, Epistle 14.26).

Women were also prominent as martyrs and suffered violently from torture and painful execution by wild animals and paid gladiators. In fact, the earliest writing definitely by a woman is the prison diary of Perpetua, a relatively wealthy matron and nursing mother who was put to death in Carthage at the beginning of the third century on the charge of being a Christian. In it, she records her testimony before the local Roman ruler and her defiance of her father’s pleas that she recant. She tells of the support and fellowship among the confessors in prison, including other women. But above all, she records her prophetic visions. Through them, she was not merely reconciled passively to her fate, but claimed the power to define the meaning of her own death. In a situation where Romans sought to use their violence against her body as a witness to their power and justice, and where the Christian editor of her story sought to turn her death into a witness to the truth of Christianity, her own writing lets us see the human being caught up in these political struggles. She actively relinquishes her female roles as mother, daughter, and sister in favor of defining her identity solely in spiritual terms. However horrifying or heroic her behavior may seem, her brief diary offers an intimate look at one early Christian woman’s spiritual journey.

EARLY CHRISTIAN WOMEN’S THEOLOGY

Study of works by and about women is making it possible to begin to reconstruct some of the theological views of early Christian women. Although they are a diverse group, certain reoccurring elements appear to be common to women’s theology-making. By placing the teaching of the Gospel of Mary side-by-side with the theology of the Corinthian women prophets, the Montanist women’s oracles, Thunder Perfect Mind, and Perpetua’s prison diary, it is possible to discern shared views about teaching and practice that may exemplify some of the contents of women’s theology:

- Jesus was understood primarily as a teacher and mediator of wisdom rather than as ruler and judge.

- Theological reflection centered on the experience of the person of the risen Christ more than the crucified savior. Interestingly enough, this is true even in the case of the martyr Perpetua. One might expect her to identify with the suffering Christ, but it is the risen Christ she encounters in her vision.

- Direct access to God is possible for all through receiving the Spirit.

- In Christian community, the unity, power, and perfection of the Spirit are present now, not just in some future time.

- Those who are more spiritually advanced give what they have freely to all without claim to a fixed, hierarchical ordering of power.

- An ethics of freedom and spiritual development is emphasized over an ethics of order and control.

- A woman’s identity and spirituality could be developed apart from her roles as wife and mother (or slave), whether she actually withdrew from those roles or not. Gender is itself contested as a “natural” category in the face of the power of God’s Spirit at work in the community and the world. This meant that potentially women (and men) could exercise leadership on the basis of spiritual achievement apart from gender status and without conformity to established social gender roles.

- Overcoming social injustice and human suffering are seen to be integral to spiritual life.

Women were also actively engaged in reinterpreting the texts of their tradition. For example, another new text, the Hypostasis of the Archons, contains a retelling of the Genesis story ascribed to Eve’s daughter Norea, in which her mother Eve appears as the instructor of Adam and his healer.

The new texts also contain an unexpected wealth of Christian imagination of the divine as feminine. The long version of the Apocryphon of John, for example, concludes with a hymn about the descent of divine Wisdom, a feminine figure here called the Pronoia of God. She enters into the lower world and the body in order to awaken the innermost spiritual being of the soul to the truth of its power and freedom, to awaken the spiritual power it needs to escape the counterfeit powers that enslave the soul in ignorance, poverty, and the drunken sleep of spiritual deadness, and to overcome illegitimate political and sexual domination. The oracle collection Thunder Perfect Mind also adds crucial evidence to women’s prophetic theology-making. This prophet speaks powerfully to women, emphasizing the presence of women in her audience and insisting upon their identity with the feminine voice of the Divine. Her speech lets the hearers transverse the distance between political exploitation and empowerment, between the experience of degradation and the knowledge of infinite self-worth, between despair and peace. It overcomes the fragmentation of the self by naming it, cherishing it, insisting upon the multiplicity of self-hood and experience.

These elements may not be unique to women’s religious thought or always result in women’s leadership, but as a constellation they point toward one type of theologizing that was meaningful to some early Christian women, that had a place for women’s legitimate exercise of leadership, and to whose construction women contributed. If we look to these elements, we are able to discern important contributions of women to early Christian theology and praxis. These elements also provide an important location for discussing some aspects of early Christian women’s spiritual lives: their exercise of leadership, their ideals, their attraction to Christianity, and what gave meaning to their self-identity as Christians.

UNDERMINING WOMEN’S PROMINENCE

Women’s prominence did not, however, go unchallenged. Every variety of ancient Christianity that advocated the legitimacy of women’s leadership was eventually declared heretical, and evidence of women’s early leadership roles was erased or suppressed.

This erasure has taken many forms. Collections of prophetic oracles were destroyed. Texts were changed. For example, at least one woman’s place in history was obscured by turning her into a man! In Romans 16:7, the apostle Paul sends greetings to a woman named Junia. He says of her and her male partner Andronicus that they are “my kin and my fellow prisoners, prominent among the apostles and they were in Christ before me.” Concluding that women could not be apostles, textual editors and translators transformed Junia into Junias, a man.

Or women’s stories could be rewritten and alternative traditions could be invented. In the case of Mary Magdalene, starting in the fourth century, Christian theologians in the Latin West associated Mary Magdalene with the unnamed sinner who anointed Jesus’ feet in Luke 7:36-50. The confusion began by conflating the account in John 12:1-8, in which Mary (of Bethany) anoints Jesus, with the anointing by the unnamed woman sinner in the accounts of Luke. Once this initial, erroneous identification was secured, Mary Magdalene could be associated with every unnamed sinful woman in the gospels, including the adulteress in John 8:1-11 and the Syro-phoenician woman with her five and more “husbands” in John 4:7-30. Mary the apostle, prophet, and teacher had become Mary the repentant whore. This fiction was invented at least in part to undermine her influence and with it the appeal to her apostolic authority to support women in roles of leadership.

Until recently the texts that survived have shown only the side that won. The new texts are therefore crucial in constructing a fuller and more accurate portrait. The Gospel of Mary, for example, argued that leadership should be based on spiritual maturity, regardless of whether one is male or female. This Gospel lets us hear an alternative voice to the one dominant in canonized works like I Timothy, which tried to silence women and insist that their salvation lies in bearing children. We can now hear the other side of the controversy over women’s leadership and see what arguments were given in favor of it.

It needs to be emphasized that the formal elimination of women from official roles of institutional leadership did not eliminate women’s actual presence and importance to the Christian tradition, although it certainly seriously damaged their capacity to contribute fully. What is remarkable is how much evidence has survived systematic attempts to erase women from history, and with them the warrants and models for women’s leadership. The evidence presented here is but the tip of an iceberg.

St. Justin Martyr: Synthesizing Philosophy and Faith; the ‘Spermatikos Logos’

Posted in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls, The Logos Doctrine (series), Theology on March 17, 2025

St. Justin Martyr (100 -166 A.D.), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian philosopher and apologist (Defender of the Faith). He was a Samaritan, born in Flavia Neapolis, Palestine, located near Jacob’s well (cf., John 4). From an early age, he studied Stoic and Platonic philosophers. At the age of 32, he converted to Christianity in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), possibly in Ephesus. Around the age of 35, he became an iterant preacher, moving from city to city in the Roman Empire, in an effort to convert educated pagans to the faith. Eventually, he ended up in Rome and spent a considerable amount of time there, debating and defending the faith. Of all his writings, only three survive: First Apology, Second Apology, and Dialogue with Trypho. St. Justin Martyr was scourged and beheaded in Rome in AD 166, under the reign of Marcus Aurelius, along with six of his followers.

Unlike Tertullian (a 2nd century Roman Carthaginian Christian author), who was opposed to Greek philosophy and viewed it as a dangerous pagan influence on Christianity, Justin Martyr viewed Greek philosophy in a more positive and optimistic light. He believed that Christianity both corrected and perfected philosophy.

While Tertullian refused to build a bridge between faith and philosophy, Justin Martyr was, on the other hand, eager to build a bridge between the two – and the name of that bridge was Logos*.

Logos, a central concept in ancient Greek philosophy, represents the divine reason or rational principle that governs the universe. The concept of Logos predates philosophical Stoicism. However, the Stoics, beginning with Zeno of Citium in the 3rd century BC, developed it into a cornerstone of their philosophical system. This Greek term, often translated as “word,” “reason,” or “plan,” is fundamental to understanding Stoic philosophical cosmology and ethics. In Stoic thought, Logos is not just an abstract principle but an active, generative force that permeates all of reality. To the Stoics, Logos represented:

• Universal Reason: Logos as the rational structure of the cosmos

• Divine Providence: The idea that the universe is governed by a benevolent plan

• Natural Law: Logos as the source of moral and physical laws

• Human Rationality: The belief that human reason is a fragment of the universal Logos

After John the Gospel Writer declared Christ to be the Logos in the prologue to his Gospel (cf., John 1, “In the beginning was the Logos…”) in about AD 90, the idea of Christ as Logos reached full bloom in the second century A.D., thanks to Justin Martyr and other early like-minded Christian philosophers.

Justin embraced the term “Logos” because it was familiar to Christians and non-Christians alike. Justin, in discussing the Logos, uses the expression, ζωτικόν πνεύμα (zotikon pneuma), vital spirit, which imparted reason as well as life to the soul. Justin understood this ζωτικόν πνεύμα as the divine principle in man. For Justin, it is a participation in the very life of the Logos. Therefore, he calls it the σπερματικόσ λόγοσ (spermatikos logos), the ‘seed of the word’, or reason in man.

This was a powerful tool in the hands of apologists like Justin. For by “Christianizing” Greek philosophy and literature, and deeming it a forerunner to Christ, the Christian apologists could easily counter the claims of the pagans who maintained that the Greeks beat the Christians to the punch. After all, the pagans said, the truths that the Christians were proclaiming as new were being taught by Greek philosophers years (read: centuries) before.

Justin maintained that the whole of Logos resided in Christ, but that all people, regardless of time or religion, contained these “seeds” of logos. Justin states,

“We have been taught that Christ is the first-born of God, and we have declared above that He is the Word [Logos] of whom every race of men were partakers; and those who lived reasonably are Christians, even though they have been thought atheists; as, among the Greeks, Socrates and Heraclitus, and men like them;” (First Apology, Chapt. 46)

Justin declared that even the pre-Christian philosophers who thought, spoke, and acted rightly did so because of the presence of the spermatikos logos in their hearts. To Justin, there is only one Logos that sows the seeds of spiritual and moral illumination in the hearts of human beings. Justin applied the spermatikos logos to explain that Christ, as the Logos, was in the world before his Incarnation, from the beginning of time, sowing the seeds of the logos in the hearts of all people. In this way, Christ united faith and philosophy. To Justin, Christ is the ultimate source of all wisdom and knowledge, even among pagans. Justin writes:

“For each man spoke well in proportion to the share he had of the spermatic word [spermatikos logos], seeing what was related to it… Whatever things were rightly said among all men, are the property of us Christians… For all the writers were able to see realities darkly through the sowing of the implanted word that was in them.” (Second Apology, Chap. 13)

According to Justin, some virtuous pagans recognized the spermatikos logos within themselves and cultivated it to a large extent. These became the great thinkers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Some, in the manner of Christ, like Socrates and Heraclitus, were even hated and persecuted for their beliefs and actions. Justin tells us the following:

“And those of the Stoic school — since, so far as their moral teaching went, they were admirable, as were also the poets in some particulars, on account of the seed of reason [the Logos] implanted in every race of men — were, we know, hated, and put to death — Heraclitus for instance, and, among those of our own time…others.” (Second Apology, Chap. 8)

People who came before the Incarnation of Jesus Christ all had the spermaticos logos, the “seed” of the Logos, implanted in them. Those Christians who came after the incarnation and resurrection of Jesus Christ had full access to all of Christ, the complete Logos. Those who came before saw through a glass darkly, but those who embrace Jesus Christ in the Christian era experience the fullness of revelation—faith and philosophy synthesized via Christ as Logos.

The Logos reveals all of God because He is God and we Christians had all the fullness of Logos because we had the revelation of Jesus Christ. The pagans did not have that. They had the spermatikos logos, but not the resurrected Christ.

Justin’s Logos was Jesus Christ himself portrayed against the backdrop of the Old Testament “Word of God” and Greek philosophy.

Contemporary Christians can easily agree with Justin Martyr that all people have within them the seeds of the Logos, the spermatikos logos. It is another way of saying that we all are created in the image of God and have an inherent knowledge of him and desire for Him.

Justin Martyr clearly represents an early, inclusive, universal Christianity encompassing all persons and religions; a time before the Church developed into an exclusive, parochial, competitive, religious institution.

Regardless of Tertullian’s fear that synthesizing faith with philosophy would “Hellenize” Christianity, Justin’s efforts ended up doing the precise opposite; faith ended up “Christianizing” Hellenism.

* “In Latin, such is the poverty of the language, there is no term at all equivalent to the Logos.” – John B. Heard. The same is true of English.

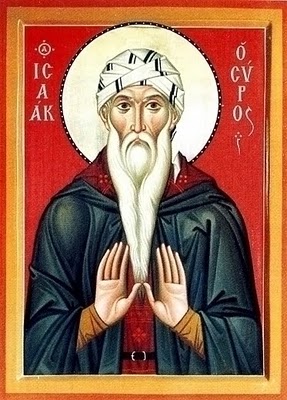

Isaac of Nineveh: On Universal Restoration

Posted in Heaven and Hell, Patristic Pearls, Universal Restoration (Apokatastasis) on March 9, 2025

St. Isaac of Nineveh – 7th century ascetic and mystic, born in modern-day Qatar, was made Bishop of Nineveh between 660-680. Especially influential in the Syriac tradition, Isaac has had a great influence in Russian culture, impacting the works of writers like Dostoyevsky.

Isaac composed dozens of homilies that he collected into seven volumes on topics of spiritual life, divine mysteries, judgements, providence, and more. Today, these seven volumes have survived in five Parts, titled from the First Part to the Fifth Part. Only the First Part was widely known outside of Aramaic speaking communities until 1983.

Some scholars argue that Isaac’s views from the Second Part appear to confirm earlier claims that Isaac advocated for universal reconciliation, or apokatastasis.

“God will not abandon anyone.” [First Part, Chap. 5]

“There was a time when sin did not exist, and there will be a time when it will not exist.” [First Part, Chap. 26]

“As a handful of sand thrown into the ocean, so are the sins of all flesh as compared with the mind of God; as a fountain that flows abundantly is not dammed by a handful of earth, so the compassion of the Creator is not overcome by the wickedness of the creatures… If He is compassionate here, we believe that there will be no change in Him; far be it from us that we should wickedly think that God could not possibly be compassionate; God’s properties are not liable to variations as those of mortals… What is hell as compared with the grace of resurrection? Come and let us wonder at the grace of our Creator.” [First Part, Chap. 50]

“It is not the way of the compassionate Maker to create rational beings in order to deliver them over mercilessly to unending affliction in punishment for things of which He knew even before they were fashioned, aware how they would turn out when He created them, and whom nonetheless He created.” [Second Part, Chap. 39]

“This is the mystery: that all creation by means of One, has been brought near to God in a mystery; then it is transmitted to all; thus all is united to Him…This action was performed for all of creation; there will, indeed, be a time when no part will fall short of the whole.” [Third Part, Chap. 5]

Gregory of Nyssa: Our Sister Macrina

Posted in Monasticism, Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians, Women in Early Christianity on March 7, 2025

Excerpt from Gregory of Nyssa: The Letters, by Ann M. Silvas, Brill, 2007

Gregory of Nyssa – Letter 19 To a certain John

The letter was written from Sebasteia in the first half of AD 380. The brief but intense cameo of Gregory’s sister, 19.6–10, is a foreshadowing and a promise of the Life of Macrina. It is the earliest documentation we have of Macrina’s existence, her way of life and her funeral led by Gregory, written less than a year after her death. The witness of her lifestyle, her conversations with him which were so formative and strengthening of his religious spirit, and above all his providential participation in her dying hours had a profound affect on him. It only needed time to absorb and reflect on these events. Then, when the occasion offered, he set out to make his remarkable sister better known to the world.

Our Sister Macrina

We had a sister who was for us a teacher of how to live, a mother in place of our mother. Such was her freedom towards God that she was for us a strong tower (Ps 60.4) and a shield of favour (Ps 5.13) as the Scripture says, and a fortified city (Ps 30.22, 59.11) and a name of utter assurance, through her freedom towards God that came of her way of life.

She dwelt in a remote part of Pontus, having exiled herself from the life of human beings. Gathered around her was a great choir of virgins whom she had brought forth by her spiritual labour pains (cf. 1 Cor 4.15, Gal 4.19) and guided towards perfection through her consummate care, while she herself imitated the life of angels in a human body.

With her there was no distinction between night and day. Rather, the night showed itself active with the deeds of light (cf. Rom 12.12–13, Eph 5.8) and day imitated the tranquility of night through serenity of life. The psalmodies resounded in her house at all times night and day.

You would have seen a reality incredible even to the eyes: the flesh not seeking its own, the stomach, just as we expect in the Resurrection, having finished with its own impulses, streams of tears poured out (cf. Jer. 9.1, Ps 79.6) to the measure of a cup, the mouth meditating the law at all times (Ps 1.2, 118.70), the ear attentive to divine things, the hand ever active with the commandments (cf. Ps 118.48). How indeed could one bring before the eyes a reality that transcends description in words?

Well then, after I left your region, I had halted among the Cappadocians, when unexpectedly I received some disturbing news of her. There was a ten days’ journey between us, so I covered the whole distance as quickly as possible and at last reached Pontus where I saw her and she saw me.

But it was the same as a traveler at noon whose body is exhausted from the sun. He runs up to a spring, but alas, before he has touched the water, before he has cooled his tongue, all at once the stream dries up before his eyes and he finds the water turned to dust.

So it was with me. At the tenth year I saw her whom I so longed to see, who was for me in place of a mother and a teacher and every good, but before I could satisfy my longing, on the third day I buried her and returned on my way.

“Daily” Bread in the Lord’s Prayer? A Word Study

Posted in First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls, Theology on January 9, 2025

Sources:

1. http://aramaicnt.org/articles/the-lords-prayer-in-galilean-aramaic/

2. Origen of Alexandria (c. 185 – c. 254): On Prayer (Περί Ευχής), Chapter XVII

The Lord’s Prayer is with little debate the most significant prayer in Christianity. Although many theological and ideological differences may divide Christians across the world, it is a prayer that unites the faith as a whole.

Within the New Testament tradition, the Prayer appears in two places. The first and more elaborate version is found in Matthew 6:9-13 where a simpler form is found in Luke 11:2-4, and the two of them share a significant amount of overlap.

The prayer’s absence from the Gospel of Mark, taken together with its presence in both Luke and Matthew, has brought some modern scholars to conclude that it is a tradition from the hypothetical “Q” source (from German: Quelle, meaning “source”) which both Luke and Matthew relied upon in many places throughout their individual writings. Given the similarities and unique character of the Matthaean and Lukan versions of the Lord’s Prayer may be evidence that what we attribute to the Greek of “Q” may ultimately trace back to an Aramaic source.

One of the trickiest problems of translating the Lord’s Prayer into Aramaic is finding out what επιούσιος (epiousios), usually translated as “daily”, originally intended. It is a unique word in Greek, only appearing twice in the all of Greek literature: Once in the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew, and the other time in the Lord’s Prayer in Luke.

This raises some curious questions that have baffled scholars. Why would Jesus have used a singular, entirely unique word? In more recent times, the bafflement has turned to a different possible solution. Jesus, someone known to have spoken Aramaic in a prayer that was originally recited in Aramaic, would not have used the Greek επιούσιος, at all. So, the question has evolved to “What Aramaic word was επιούσιος supposed to represent?” It would have to be something unique or difficult enough that whoever translated it into Greek needed to coin a word to express or preserve some meaning that they thought was important, or something that they couldn’t quite wrap the Greek language around.

The first question to answer is the meaning of the unique koine Greek word ἐπιούσιον (epiousion). To do this, we consult the writings of Origen of Alexandria. Origen was a third century native koine Greek speaker, head of the famed Catechetical School of Alexandria, the greatest theologian of the early church, and first to perform an exegesis of the Lord’s Prayer (ca. AD 240).

Origen begins: ”Let us now consider what the word epiousion, needful, means. First of all it should be known that the word epiousion is not found in any Greek writer whether in philosophy or in common usage, but seems to have been formed by the evangelists. At least Matthew and Luke, in having given it to the world, concur in using it in identical form.”

Origen concludes his in-depth discussion of epiousion, needful, by stating, “Needful, therefore, is the bread which corresponds most closely to our rational nature and is akin to our very essence, which invests the soul at once with well being and with strength, and, since the Word of God is immortal, imparts to its eater its own immortality.”

In Aramaic, the best fit for επιούσιος is probably the word çorak. It comes from the root çrk, which means to be poor, to need, or to be necessary. It is a very common word in Galilean Aramaic that is used in a number of senses to express both need and thresholds of necessity, such as “as much as is required” (without further prepositions) or with pronominal suffixes “all that [pron.] needs” (çorki = “All that I need”; çorkak = “All that you need”; etc.). Given this multi-faceted nature of the word, it’s hard to find a one-to-one Greek word that would do the job, and επιούσιος is a very snug fit in the context of the Prayer’s petition. This might even give us a hint that the Greek translator literally read into it a bit.

The Aramaic word yelip is another possible solution. It is interesting to note that it comes from the root yalap or “to learn.” Etymologically speaking, learning is a matter of repetition and routine, and this connection may play off the idea of regular physical bread, but actually mean “daily learning from God” (i.e. that which is necessary for living, as one cannot live off of bread alone).

Bottom line:

Origen’s understanding of epiousion in his context of needful certainly has no connection or relationship to a simplistic English translation of epiousion as “daily’. Nor is the translation of epiousion as “daily” supported by either hypothetical original Aramaic word çorkak or yelip.

In fact, a translation of epiousion as “daily” makes this petition in the Lord’s Prayer (Matt. 6:11) directly contradict Jesus’ lengthy admonition 14 verses later, starting at Matt 6:25:

25 “Therefore I say to you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink; nor about your body, what you will put on. Is not life more than food and the body more than clothing?

26 “Look at the birds of the air, for they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they?

31 “Therefore do not worry, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or ‘What shall we drink?’ or ‘What shall we wear?’

32 “For after all these things the Gentiles seek. For your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things.

33 “But seek first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things shall be added to you.

The Gospel writers of Matthew and Luke both used the same totally unique Greek word solely in the context of the Lord’s Prayer. There were other frequently used koine Greek words available to express the simple idea of “daily”. Perhaps the unique use of epiousion was not accidental or coincidental, but needed to express the intent of the original Aramaic prayer. Origen may provide the best insight into the intended meaning of ἐπιούσιον as needful of the supra-essential Word of God.

“And we believe in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church.”

Posted in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, Monasticism on December 28, 2024

In the original koine Greek of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed of AD 381, the subject line reads: Εἰς μίαν, Ἁγίαν, Καθολικὴν καὶ Ἀποστολικὴν Ἐκκλησίαν.

I find it sadly ironic that The Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, as it is recited in most worship services today, uses the first person singular (“I believe…”/”Πιστεύω”) rather than the first person plural (“We believe…”/”Πιστεύομεν”) as it was enacted at the first and second ecumenical councils (Nicaea AD 325 and Constantinople AD 381) of the undivided Church. In this self-centered, affluent, secularized, and fragmented Western world, I guess the shift from a collective “we” to an individual “I” should come as no surprise.

Christianity became the State Religion of the Roman Empire in AD 380. Since becoming that key religious institution in the social and political infrastructure of worldly power, very little has changed to this day, regardless of the form or character of the Church’s earthbound imperial partners. Fr. Richard Rohr, OFM, calls it the Church’s 1,700 year addiction to Power, Prestige, and Possessions.

Let’s analyze our subject line from the Creed: “And we believe in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church.”

The institutional Christian Church was no longer “One” after 451 AD; increasingly less “Holy” after 313 AD; no longer “Catholic” after 1054 (worse after 1517); and “Apostolic” only in origin (and Rome’s claim to Peter and Constantinople’s claim to Andrew are tenuous, at best.). So, nothing in this line from the Creed has been objectively true in more than 1,000 years. Reciting this line from the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed now is not so much a proclamation of faith, as a largely an unsupportable exercise in wishful thinking. Don’t believe it? “Google” the dated Church events and read for yourself.

Until the issues raised in the preceding paragraphs are meaningfully addressed (read: confession and repentance) by the legacy institutional Church, I think it will continue to shrink in numbers, authority, influence, and credibility. I believe the Ecclesia (Ἐκκλησία) of scripture will endure and eventually prevail; the institutional imperial Church, not so much. And Ecclesia and Church are not the same thing, in spite of institutional protests to the contrary.

In the meantime, solitary Christian hermits patiently remain in silent prayer within their virtual deserts.

von Balthasar on Gregory of Nyssa

Posted in Concept of "Person" (series), Ekklesia and church, Essence and Energies (series), Patristic Pearls, The "Nous" (series), The Cappadocians, The Holy Trinity on December 26, 2024

Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905–1988) – Hans Urs von Balthasar was a Swiss theologian and Catholic priest who is considered one of the most important Catholic theologians of the 20th century. Over the course of his life, he authored 85 books, over 500 articles and essays, and almost 100 translations.

Excerpt from Hans Urs von Balthasar: Presence and Thought: Essay on the Religious Philosophy of Gregory of Nyssa (1988)

“Less brilliant and prolific than his great master Origen, less cultivated than his friend Gregory Nazianzen, less practical than his brother Basil, he [Gregory of Nyssa] nonetheless outstrips them all in the profundity of his thought, for he knew better than anyone how to transpose ideas inwardly from the spiritual heritage of ancient Greece into a Christian mode.”

Prayer Ropes and Rosaries

Posted in Ekklesia and church, Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, Monasticism, New Nuggets, Patristic Pearls on December 21, 2024

Both the prayer rope and the rosary are revered traditional aids to Christian prayer, yet each has its own unique origin, symbolism, and devotional use.

The Prayer Rope, now largely associated with the Eastern Orthodox Church, is a loop of knots (each knot containing seven crosses), usually made of wool, that is used to focus and intensify prayer, particularly the Jesus Prayer. It acts as a physical guide for a repeated, meditative style of prayer, allowing practitioners to keep count while reflecting and meditating. The prayer rope has its beginnings in early fourth century Christian monasticism in the Egyptian Desert, where it was devised as a tool to aid in the ascetic practice of continuous prayer (1 Thes. 5:17).

Origins: The prayer rope is known as a ‘komboskini’ in Greek and ‘chotki’ in Russian. The prayer rope owes its origins to St. Pachomius the Great, a fourth century “Desert Father” in upper Egypt and founder of cenobitic monasticism (a monastic tradition that stresses community life, over the older, eremitic, or solitary tradition). St. Pachomius established the prayer rope as a practical solution for the monks under his supervision to count prayers and prostrations consistently. The prayer rope evolved as a useful instrument for monks to keep track of their prayers, particularly the Jesus Prayer, without distraction. It gradually took on a deeper spiritual value, with each knot symbolizing a request for mercy and humility.

Symbolic Significance: Wool knots, each knot containing seven crosses, are commonly used on traditional prayer ropes to represent Christ’s flock and the shepherd’s care. The number of knots in a prayer rope varies; typically 33 (Christ’s age at crucifixion), 50, or 100.

Traditional Use: In Orthodox Christian practice, the prayer rope is typically used for private prayer in reciting the Jesus Prayer, acting as a physical and spiritual guide to help the mind (nous) and heart concentrate on prayer.

The Rosary, strongly associated with the Roman Catholic Church, is a string of beads that ends with a crucifix and is used to guide Catholics through a sequence of prayers that reflect on the lives of Christ and the Virgin Mary. Each bead signifies a specific prayer, such as the Hail Mary, and each set of beads makes a ‘decade’ that corresponds to a mystery in Christ’s life. The rosary has a long history, dating back to the Middle Ages when it first arose as a popular form of laity devotion, eventually becoming a prominent practice in Catholic piety.

Origins: The rosary is typically identified with Saint Dominic in the early 13th century. The rosary began as a simple way for lay people to join in the monastic practice of reciting the Psalms, but has since evolved into a systematic form of prayer. The rosary prayers are split into decades, each with ten Hail Marys, an Our Father, and a Glory Be, and are frequently accompanied by meditations on the Mysteries of the Rosary.

Symbolic Significance: Each rosary bead represents a prayer as well as a step in the meditation journey through Jesus Christ’s and the Virgin Mary’s lives. The rosary culminates with a crucifix, which represents Christ’s sacrifice.

Traditional Use: Roman Catholics utilize the rosary for both personal meditation and social worship. It is frequently prayed privately for personal spiritual development or in groups for social objectives and celebrations.