Archive for category Theology

St. Justin Martyr: Synthesizing Philosophy and Faith; the ‘Spermatikos Logos’

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls, The Logos Doctrine (series), Theology on March 17, 2025

St. Justin Martyr (100 -166 A.D.), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian philosopher and apologist (Defender of the Faith). He was a Samaritan, born in Flavia Neapolis, Palestine, located near Jacob’s well (cf., John 4). From an early age, he studied Stoic and Platonic philosophers. At the age of 32, he converted to Christianity in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), possibly in Ephesus. Around the age of 35, he became an iterant preacher, moving from city to city in the Roman Empire, in an effort to convert educated pagans to the faith. Eventually, he ended up in Rome and spent a considerable amount of time there, debating and defending the faith. Of all his writings, only three survive: First Apology, Second Apology, and Dialogue with Trypho. St. Justin Martyr was scourged and beheaded in Rome in AD 166, under the reign of Marcus Aurelius, along with six of his followers.

Unlike Tertullian (a 2nd century Roman Carthaginian Christian author), who was opposed to Greek philosophy and viewed it as a dangerous pagan influence on Christianity, Justin Martyr viewed Greek philosophy in a more positive and optimistic light. He believed that Christianity both corrected and perfected philosophy.

While Tertullian refused to build a bridge between faith and philosophy, Justin Martyr was, on the other hand, eager to build a bridge between the two – and the name of that bridge was Logos*.

Logos, a central concept in ancient Greek philosophy, represents the divine reason or rational principle that governs the universe. The concept of Logos predates philosophical Stoicism. However, the Stoics, beginning with Zeno of Citium in the 3rd century BC, developed it into a cornerstone of their philosophical system. This Greek term, often translated as “word,” “reason,” or “plan,” is fundamental to understanding Stoic philosophical cosmology and ethics. In Stoic thought, Logos is not just an abstract principle but an active, generative force that permeates all of reality. To the Stoics, Logos represented:

• Universal Reason: Logos as the rational structure of the cosmos

• Divine Providence: The idea that the universe is governed by a benevolent plan

• Natural Law: Logos as the source of moral and physical laws

• Human Rationality: The belief that human reason is a fragment of the universal Logos

After John the Gospel Writer declared Christ to be the Logos in the prologue to his Gospel (cf., John 1, “In the beginning was the Logos…”) in about AD 90, the idea of Christ as Logos reached full bloom in the second century A.D., thanks to Justin Martyr and other early like-minded Christian philosophers.

Justin embraced the term “Logos” because it was familiar to Christians and non-Christians alike. Justin, in discussing the Logos, uses the expression, ζωτικόν πνεύμα (zotikon pneuma), vital spirit, which imparted reason as well as life to the soul. Justin understood this ζωτικόν πνεύμα as the divine principle in man. For Justin, it is a participation in the very life of the Logos. Therefore, he calls it the σπερματικόσ λόγοσ (spermatikos logos), the ‘seed of the word’, or reason in man.

This was a powerful tool in the hands of apologists like Justin. For by “Christianizing” Greek philosophy and literature, and deeming it a forerunner to Christ, the Christian apologists could easily counter the claims of the pagans who maintained that the Greeks beat the Christians to the punch. After all, the pagans said, the truths that the Christians were proclaiming as new were being taught by Greek philosophers years (read: centuries) before.

Justin maintained that the whole of Logos resided in Christ, but that all people, regardless of time or religion, contained these “seeds” of logos. Justin states,

“We have been taught that Christ is the first-born of God, and we have declared above that He is the Word [Logos] of whom every race of men were partakers; and those who lived reasonably are Christians, even though they have been thought atheists; as, among the Greeks, Socrates and Heraclitus, and men like them;” (First Apology, Chapt. 46)

Justin declared that even the pre-Christian philosophers who thought, spoke, and acted rightly did so because of the presence of the spermatikos logos in their hearts. To Justin, there is only one Logos that sows the seeds of spiritual and moral illumination in the hearts of human beings. Justin applied the spermatikos logos to explain that Christ, as the Logos, was in the world before his Incarnation, from the beginning of time, sowing the seeds of the logos in the hearts of all people. In this way, Christ united faith and philosophy. To Justin, Christ is the ultimate source of all wisdom and knowledge, even among pagans. Justin writes:

“For each man spoke well in proportion to the share he had of the spermatic word [spermatikos logos], seeing what was related to it… Whatever things were rightly said among all men, are the property of us Christians… For all the writers were able to see realities darkly through the sowing of the implanted word that was in them.” (Second Apology, Chap. 13)

According to Justin, some virtuous pagans recognized the spermatikos logos within themselves and cultivated it to a large extent. These became the great thinkers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Some, in the manner of Christ, like Socrates and Heraclitus, were even hated and persecuted for their beliefs and actions. Justin tells us the following:

“And those of the Stoic school — since, so far as their moral teaching went, they were admirable, as were also the poets in some particulars, on account of the seed of reason [the Logos] implanted in every race of men — were, we know, hated, and put to death — Heraclitus for instance, and, among those of our own time…others.” (Second Apology, Chap. 8)

People who came before the Incarnation of Jesus Christ all had the spermaticos logos, the “seed” of the Logos, implanted in them. Those Christians who came after the incarnation and resurrection of Jesus Christ had full access to all of Christ, the complete Logos. Those who came before saw through a glass darkly, but those who embrace Jesus Christ in the Christian era experience the fullness of revelation—faith and philosophy synthesized via Christ as Logos.

The Logos reveals all of God because He is God and we Christians had all the fullness of Logos because we had the revelation of Jesus Christ. The pagans did not have that. They had the spermatikos logos, but not the resurrected Christ.

Justin’s Logos was Jesus Christ himself portrayed against the backdrop of the Old Testament “Word of God” and Greek philosophy.

Contemporary Christians can easily agree with Justin Martyr that all people have within them the seeds of the Logos, the spermatikos logos. It is another way of saying that we all are created in the image of God and have an inherent knowledge of him and desire for Him.

Justin Martyr clearly represents an early, inclusive, universal Christianity encompassing all persons and religions; a time before the Church developed into an exclusive, parochial, competitive, religious institution.

Regardless of Tertullian’s fear that synthesizing faith with philosophy would “Hellenize” Christianity, Justin’s efforts ended up doing the precise opposite; faith ended up “Christianizing” Hellenism.

* “In Latin, such is the poverty of the language, there is no term at all equivalent to the Logos.” – John B. Heard. The same is true of English.

“Daily” Bread in the Lord’s Prayer? A Word Study

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls, Theology on January 9, 2025

Sources:

1. http://aramaicnt.org/articles/the-lords-prayer-in-galilean-aramaic/

2. Origen of Alexandria (c. 185 – c. 254): On Prayer (Περί Ευχής), Chapter XVII

The Lord’s Prayer is with little debate the most significant prayer in Christianity. Although many theological and ideological differences may divide Christians across the world, it is a prayer that unites the faith as a whole.

Within the New Testament tradition, the Prayer appears in two places. The first and more elaborate version is found in Matthew 6:9-13 where a simpler form is found in Luke 11:2-4, and the two of them share a significant amount of overlap.

The prayer’s absence from the Gospel of Mark, taken together with its presence in both Luke and Matthew, has brought some modern scholars to conclude that it is a tradition from the hypothetical “Q” source (from German: Quelle, meaning “source”) which both Luke and Matthew relied upon in many places throughout their individual writings. Given the similarities and unique character of the Matthaean and Lukan versions of the Lord’s Prayer may be evidence that what we attribute to the Greek of “Q” may ultimately trace back to an Aramaic source.

One of the trickiest problems of translating the Lord’s Prayer into Aramaic is finding out what επιούσιος (epiousios), usually translated as “daily”, originally intended. It is a unique word in Greek, only appearing twice in the all of Greek literature: Once in the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew, and the other time in the Lord’s Prayer in Luke.

This raises some curious questions that have baffled scholars. Why would Jesus have used a singular, entirely unique word? In more recent times, the bafflement has turned to a different possible solution. Jesus, someone known to have spoken Aramaic in a prayer that was originally recited in Aramaic, would not have used the Greek επιούσιος, at all. So, the question has evolved to “What Aramaic word was επιούσιος supposed to represent?” It would have to be something unique or difficult enough that whoever translated it into Greek needed to coin a word to express or preserve some meaning that they thought was important, or something that they couldn’t quite wrap the Greek language around.

The first question to answer is the meaning of the unique koine Greek word ἐπιούσιον (epiousion). To do this, we consult the writings of Origen of Alexandria. Origen was a third century native koine Greek speaker, head of the famed Catechetical School of Alexandria, the greatest theologian of the early church, and first to perform an exegesis of the Lord’s Prayer (ca. AD 240).

Origen begins: ”Let us now consider what the word epiousion, needful, means. First of all it should be known that the word epiousion is not found in any Greek writer whether in philosophy or in common usage, but seems to have been formed by the evangelists. At least Matthew and Luke, in having given it to the world, concur in using it in identical form.”

Origen concludes his in-depth discussion of epiousion, needful, by stating, “Needful, therefore, is the bread which corresponds most closely to our rational nature and is akin to our very essence, which invests the soul at once with well being and with strength, and, since the Word of God is immortal, imparts to its eater its own immortality.”

In Aramaic, the best fit for επιούσιος is probably the word çorak. It comes from the root çrk, which means to be poor, to need, or to be necessary. It is a very common word in Galilean Aramaic that is used in a number of senses to express both need and thresholds of necessity, such as “as much as is required” (without further prepositions) or with pronominal suffixes “all that [pron.] needs” (çorki = “All that I need”; çorkak = “All that you need”; etc.). Given this multi-faceted nature of the word, it’s hard to find a one-to-one Greek word that would do the job, and επιούσιος is a very snug fit in the context of the Prayer’s petition. This might even give us a hint that the Greek translator literally read into it a bit.

The Aramaic word yelip is another possible solution. It is interesting to note that it comes from the root yalap or “to learn.” Etymologically speaking, learning is a matter of repetition and routine, and this connection may play off the idea of regular physical bread, but actually mean “daily learning from God” (i.e. that which is necessary for living, as one cannot live off of bread alone).

Bottom line:

Origen’s understanding of epiousion in his context of needful certainly has no connection or relationship to a simplistic English translation of epiousion as “daily’. Nor is the translation of epiousion as “daily” supported by either hypothetical original Aramaic word çorkak or yelip.

In fact, a translation of epiousion as “daily” makes this petition in the Lord’s Prayer (Matt. 6:11) directly contradict Jesus’ lengthy admonition 14 verses later, starting at Matt 6:25:

25 “Therefore I say to you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink; nor about your body, what you will put on. Is not life more than food and the body more than clothing?

26 “Look at the birds of the air, for they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they?

31 “Therefore do not worry, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or ‘What shall we drink?’ or ‘What shall we wear?’

32 “For after all these things the Gentiles seek. For your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things.

33 “But seek first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things shall be added to you.

The Gospel writers of Matthew and Luke both used the same totally unique Greek word solely in the context of the Lord’s Prayer. There were other frequently used koine Greek words available to express the simple idea of “daily”. Perhaps the unique use of epiousion was not accidental or coincidental, but needed to express the intent of the original Aramaic prayer. Origen may provide the best insight into the intended meaning of ἐπιούσιον as needful of the supra-essential Word of God.

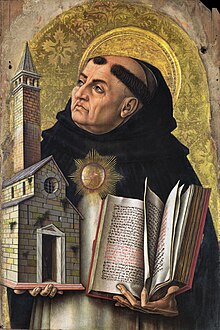

Thomas Aquinas: “… all that I have written seems to me as so much straw”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, Theology on December 10, 2024

Thomas Aquinas OP (c. 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest, the foremost Scholastic thinker, as well one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the Western tradition. Thomas’s best-known work is the unfinished Summa Theologica, or Summa Theologiae (1265–1274). As a Doctor of the Church, Thomas Aquinas is considered one of the Roman Catholic Church’s greatest theologians and philosophers.

On December 6th, 1273, while Thomas Aquinas was celebrating Holy Communion during the Feast of Saint Nicholas, he received a revelation that so affected him he called his principal work, the Summa Theologica, nothing more than “straw” and left it unfinished.

Aquinas described his Divine Experience: “The most perfect union with God is the most perfect human happiness and the goal of the whole of the human life, a gift that must be given to us by God.”

When his friend and secretary tried to encourage Aquinas to write more, he replied:

“I can do no more. The end of my labors has come. Such things have been revealed to me that all that I have written seems to me as so much straw. Now I await the end of my life after that of my works.”

Aquinas would die just three short months later. The Great Doctor finally got it right, I think. Experience (theoria) trumps reason.

An Orthodox view on Heaven and Hell

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Heaven and Hell, Theology on November 2, 2024

From the The Orthodox Church in America (OCA)

The Kingdom of heaven is already in the midst of those who live the spiritual life. What the spiritual person knows in the Holy Spirit, in Christ and the Church, will come with power and glory for all men to behold at the end of the ages.

The final coming of Christ will be the judgment of all men. His very presence will be the judgment. Now men can live without the love of Christ in their lives. They can exist as if there were no God, no Christ, no Spirit, no Church, no spiritual life. At the end of the ages this will no longer be possible. All men will have to behold the Face of Him who “for us men and our salvation came down from heaven and was incarnate . . . who was crucified under Pontius Pilate, and suffered and was buried . . .” (Nicene Creed). All will have to look at Him whom they have crucified by their sins: Him “who was dead and is alive again” (Rev 1.17–18).

For those who love the Lord, His Presence will be infinite joy, paradise and eternal life. For those who hate the Lord, the same Presence will be infinite torture, hell and eternal death. The reality for both the saved and the damned will be exactly the same when Christ “comes in glory, and all angels with Him,” so that “God may be all in all” (1 Cor 15–28). Those who have God as their “all” within this life will finally have divine fulfillment and life. For those whose “all” is themselves and this world, the “all” of God will be their torture, their punishment and their death. And theirs will be “weeping and gnashing of teeth” (Mt 8.21, et al.).

The Son of Man will send His angels and they will gather out of His kingdom all causes of sin and all evil doers, and throw them into the furnace of fire; there men will weep and gnash their teeth. Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the Kingdom of their Father (Mt 13.41–43).

According to the saints, the “fire” that will consume sinners at the coming of the Kingdom of God is the same “fire” that will shine with splendor in the saints. It is the “fire” of God’s love; the “fire” of God Himself who is Love. “For our God is a consuming fire” (Heb 12.29) who “dwells in unapproachable light” (1 Tim 6.16). For those who love God and who love all creation in Him, the “consuming fire” of God will be radiant bliss and unspeakable delight. For those who do not love God, and who do not love at all, this same “consuming fire” will be the cause of their “weeping” and their “gnashing of teeth.”

Thus it is the Church’s spiritual teaching that God does not punish man by some material fire or physical torment. God simply reveals Himself in the risen Lord Jesus in such a glorious way that no man can fail to behold His glory. It is the presence of God’s splendid glory and love that is the scourge of those who reject its radiant power and light.

. . . those who find themselves in hell will be chastised by the scourge of love. How cruel and bitter this torment of love will be! For those who understand that they have sinned against love, undergo no greater suffering than those produced by the most fearful tortures. The sorrow which takes hold of the heart, which has sinned against love, is more piercing than any other pain. It is not right to say that the sinners in hell are deprived of the love of God . . . But love acts in two ways, as suffering of the reproved, and as joy in the blessed! (Saint Isaac of Syria, Mystic Treatises).

This teaching is found in many spiritual writers and saints: Saint Maximus the Confessor, the novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky. At the end of the ages God’s glorious love is revealed for all to behold in the face of Christ. Man’s eternal destiny—heaven or hell, salvation or damnation—depends solely on his response to this love.

Paradise and Hell

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, Heaven and Hell, Theology on October 8, 2024

The Beatitudes- Fresh Eyes on Ancient Language

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, New Nuggets, Theology on May 2, 2024

A new translation by David Bentley Hart

The Eight Beatitudes in the Gospel of Matthew (Chap. 5, verses 3-10)1

3 Μακάριοι οἱ πτωχοὶ τῷ πνεύματι, ὅτι αὐτῶν ἐστιν ἡ βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν.

How blissful2 the destitute, abject3 in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of the heavens.

4 μακάριοι οἱ πενθοῦντες, ὅτι αὐτοὶ παρακληθήσονται.

How blissful those who mourn, for they shall be aided.

5 μακάριοι οἱ πραεῖς, ὅτι αὐτοὶ κληρονομήσουσι τὴν γῆν.

How blissful the gentle, for they shall inherit the earth.

6 μακάριοι οἱ πεινῶντες καὶ διψῶντες τὴν δικαιοσύνην, ὅτι αὐτοὶ χορτασθήσονται.

How blissful those who hunger and thirst for what is right, for they shall feast.

7 μακάριοι οἱ ἐλεήμονες, ὅτι αὐτοὶ ἐλεηθήσονται.

How blissful the merciful, for they shall receive mercy.

8 μακάριοι οἱ καθαροὶ τῇ καρδίᾳ, ὅτι αὐτοὶ τὸν θεὸν ὄψονται.

How blissful the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

9 μακάριοι οἱ εἰρηνοποιοί, ὅτι αὐτοὶ υἱοὶ θεοῦ κληθήσονται.

How blissful the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.

10 μακάριοι οἱ δεδιωγμένοι ἕνεκεν δικαιοσύνης, ὅτι αὐτῶν ἐστιν ἡ βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν.

How blissful those who have been persecuted for the sake of what is right, for theirs is the Kingdom of the heavens.

1 Translation by David Bentley Hart. The New Testament, 2nd Edition, Yale University Press, 2023.

2 μακάριος (makarios): “blessed”, “happy”, “fortunate”, “prosperous”, but originally with a connotation of divine or heavenly bliss.

3 A πτῶχος (ptōchos) is a poor man or beggar, but with the connotation of one who is abject: cowering or cringing.

St. Gregory of Nyssa: “Epektasis (ἐπέκτασις)- The soul’s eternal ‘straining toward’ God”.

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Monasticism, Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians, Theology on April 20, 2023

“Brothers, I do not yet reckon myself to have seized hold, save of one thing: Both forgetting the things lying behind and also stretching out [ἐπεκτεινόμενος] to the things lying ahead,”

Philippians 3:13 from The New Testament- a translation by David Bentley Hart

_________________________________________________________________________

Background – A Brief Summary of Gregory of Nyssa’s Theology

In Gregory’s account of creation, the nature-energies distinction, developed to counter Eunomius, a defender of the 4th century Arian heresy, becomes extended into a general cosmological principle.

To Gregory, the essence of God is incomprehensible, transcendent, and cannot be defined by any set of human concepts. When speaking of God’s essence, or ousia, all that can be said is what that essence is not (Against Eunomius II, IV). In saying this, Gregory anticipates the via negativa (apophatic) theology of Pseudo-Dionysius (5th century) and much of subsequent Orthodox theological thought.

If God is simply some transcendent, unknowable entity, what possible relation to the world could God ever have? Gregory answers these questions by distinguishing between God’s “nature” (phusis) and God’s “energies” (energeiai). God’s energies are the projection of the divine nature into the world; initially creating it and ultimately guiding it to its appointed destination (Beatitudes VI). The idea of God’s energies in Gregory’s theology emphasizes God’s actual presence in those parts of creation which are perfected just because of that presence. Whereas God’s nature is totally transcendent and unknowable, God’s energies are immanent and knowable to mankind. With this revelation, Gregory anticipates the more famous substance-energies distinction of the 14th century Byzantine theologian Gregory Palamas.

Gregory’s view of human nature is dominated by his belief that humans were created in the image of God. This means that because God’s transcendent nature projects energies out into the world, we would expect the same structural relationship to exist in human beings between their minds and their bodies. In fact, that is precisely what Gregory argues concerning the human nous (a word that was traditionally translated as “mind”, but by the 4th century included the Christian idea of its nature also extending beyond and separate from the physical world).

The most important characteristic of the nature of the nous is that it provides for a unity of consciousness; where the myriad perceptions from various sense organs are all coordinated with each other. Using the metaphor of a city in which family members come in by various gates but all meet somewhere inside, Gregory’s assertion is that this can occur only if we presuppose a transcendent self to which all of one’s experiences are referred (Making of Man 10). But Gregory maintains that this unity of consciousness is entirely mysterious, much like the mysterious nature of the Godhead (Making of Man 11).

Yet the nous is also extended by its energies throughout the body, which includes our ordinary sensory and psychological experiences as well as our discursive, rational mind (dianoia) (Making of Man 15; Soul and Resurrection).

There are two further important characteristics of the human nous according to Gregory. First, because the human nous is created in the image of God, it possesses a certain “dignity of royalty” (to tes basileias axioma) that is lacking in the rest of creation. Second, the nous is free. Gregory derives the freedom of the nous from the freedom of God. For God, being dependent on nothing, governs the universe through the free exercise of will; and the nous is created in God’s image (Making of Man 4).

Epektasis – the eternal ‘stretching and straining’ of the soul toward God

This concept of epektasis features heavily throughout the writings of Gregory of Nyssa (most especially in his Life of Moses and Homilies on the Song of Songs). His work leans toward an ascetic, mystical approach to the faith. Gregory believed that man’s ultimate purpose was to grow in participation in the divine. Since God is transcendent and infinite and man is created and finite, he reasoned that man could never reach a point where he fully participated in God; hence the need for the concept of epektasis. Gregory rejected the more typical view that happiness and perfection are found in attaining a concrete spiritual goal. Rather, he suggested, since humanity is incapable of reaching the actual transcendent perfection of God, purpose and meaning are found in progress toward that relationship standard. Gregory’s views on spiritualty had an early and lasting impact on the Eastern Orthodox interpretation of theosis.

Epektasis is derived from a Greek word found in verses such as Philippians 3:13, where it is translated as “stretching out.” Epectasis, like askesis, is a term from athletics. It implies something that is becoming, developing, being strived for. It has alternately been understood as “evolving” or “growing.” As it pertains to Christian theology, epektasis implies that true joy in Christian living is found in the process of spiritual growth and development. That is, it is the internal change we experience that produces a sense of happiness, not the achievement of any particular goal. Specifically, epektasis emphasizes the need for continual “spiritual transformation” and suggests this process will continue forever in eternity. For Gregory, it is the journey that is important.

As Gregory puts it, “Deity is in everything, penetrating it, embracing it, and seated in it” (Great Catechism 25). So, we directly experience the divine energies in the only thing in the universe that we can view from within – ourselves. God’s energies are always a force for good. Thus, we encounter them in the experience of virtues such as purity, passionlessness (apatheia), sanctity, and simplicity in our own moral character. “if . . . these things be in you,” Gregory concludes, “God is indeed in you” (Beatitudes VI).

Gregory tells us epektasis also imposes certain obligations on us in relation to both others and ourselves. To others we owe mercy (Beatitudes V) and the Christian virtue of agape (Beatitudes VII). To ourselves we owe the effort to overcome (through askesis; athletic training) the deficiencies and shortcomings in our likeness to God; for we are unable to contemplate God directly, and morally our free will has been compromised by the passions (pathe). Thus, with respect to ourselves we must continuously stretch out our souls (epektasis; like a straining athlete), toward intellectual and moral perfection (Beatitudes III).

_________________________________________________________________________________

“Whereby he has given us his precious and majestic promises, so that through these you may become communicants in the divine nature, having escaped from the decay that is in the cosmos on account of desire.”

2 Peter 1:4 from The New Testament- a translation by David Bentley Hart

___________________________________________

Text references (by Gregory of Nyssa):

Against Eunomius

Homilies on the Beatitudes

On the Making of Man

On the Soul and the Resurrection

The Life of Moses

Homilies on the Song of Songs

The Great Catechism

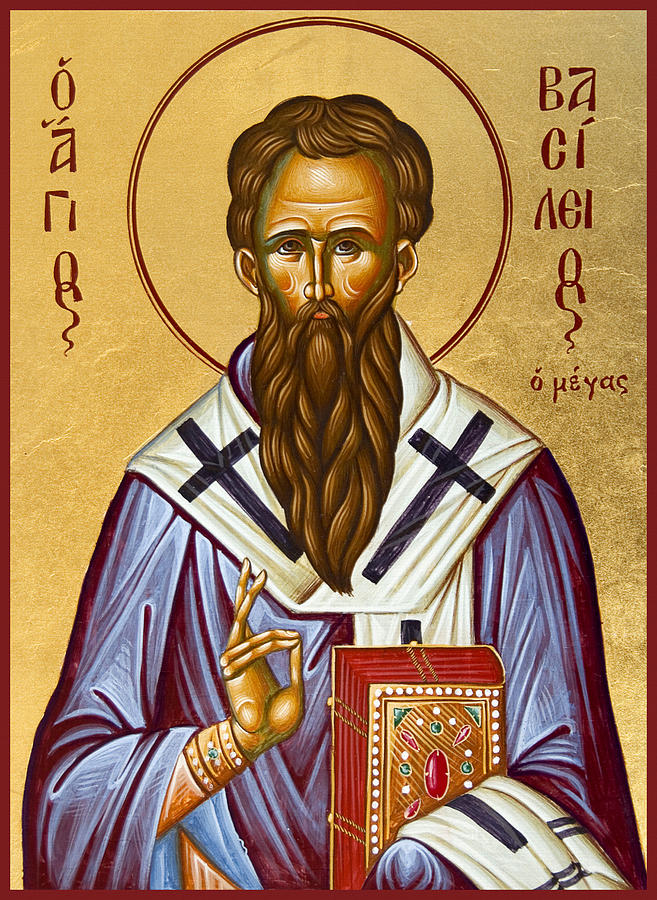

St. Basil the Great: “On the Holy Spirit”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Monasticism, Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians, The Holy Trinity, Theology on April 6, 2023

St. Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great (330 – January 379), was a bishop of Caesarea Mazaca in Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey). He was an influential theologian who supported the Nicene Creed and opposed the heresies of the early Christian church. Together with Pachomius, he is remembered as a father of communal (coenobitic) monasticism in Eastern Christianity. Basil, together with his brother Gregory of Nyssa and his friend Gregory of Nazianzus, are collectively referred to as the Cappadocian Fathers.

“Just as when a sunbeam falls on bright and transparent bodies, they themselves become brilliant too, and shed forth a fresh brightness from themselves, so souls wherein the Spirit dwells, illuminated by the Spirit, themselves become spiritual, and send forth their grace to others. Hence comes foreknowledge of the future, understanding of mysteries, apprehension of what is hidden, distribution of good gifts, the heavenly citizenship, a place in the chorus of angels, joy without end, abiding in God, the being made like to God, and, highest of all, the being made God. Such, then, to instance a few out of many, are the conceptions concerning the Holy Spirit, which we have been taught to hold concerning His greatness, His dignity, and His operations, by the oracles of the Spirit themselves.”

~ from: On the Holy Spirit (De Spiritu Sancto), Chap. 9

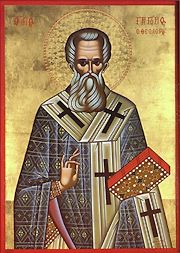

St. Gregory of Nazianzus: “… the confession of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost.”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians, The Holy Trinity, Theology on April 6, 2023

St. Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 329 – 25 January 390), also known as Gregory the Theologian or Gregory Nazianzen, was a 4th-century Archbishop of Constantinople, theologian, and one of the Cappadocian Fathers (along with Basil the Great and Gregory of Nyssa). He is widely considered the most accomplished rhetorical stylist of the patristic age. Gregory made a significant impact on the shape of Trinitarian theology among both Greek and Latin-speaking theologians, and he is remembered as the “Trinitarian Theologian”.

“Besides all this and before all, keep I pray you the good deposit, by which I live and work, and which I desire to have as the companion of my departure; with which I endure all that is so distressful, and despise all delights; the confession of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost. This I commit unto you today; with this I will baptize you and make you grow. This I give you to share, and to defend all your life, the One Godhead and Power, found in the Three in Unity, and comprising the Three separately, not unequal, in substances or natures, neither increased nor diminished by superiorities or inferiorities; in every respect equal, in every respect the same; just as the beauty and the greatness of the heavens is one; the infinite conjunction of Three Infinite Ones, Each God when considered in Himself; as the Father so the Son, as the Son so the Holy Ghost; the Three One God when contemplated together; Each God because Consubstantial; One God because of the Monarchia. No sooner do I conceive of the One than I am illumined by the Splendour of the Three; no sooner do I distinguish Them than I am carried back to the One. When I think of any One of the Three I think of Him as the Whole, and my eyes are filled, and the greater part of what I am thinking of escapes me. I cannot grasp the greatness of That One so as to attribute a greater greatness to the Rest. When I contemplate the Three together, I see but one torch, and cannot divide or measure out the Undivided Light.”

~ from The Orations and Letters of Saint Gregory Nazianzus . Oration 40, XLI.

Rohr: “Finding God in the depths of silence”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, New Nuggets, Theology on January 24, 2023

Fr. Richard Rohr OFM, a Sojourners contributing editor, is founder of the Centre for Action and Contemplation http://www.cacradicalgrace.org in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

This article was first published in the March 2013 edition of Sojourners

Reprinted with permission from Sojourners, (800) 714-7474, http://www.sojo.net

Source: http://www.goodsams.org.au/good-oil/finding-god-in-the-depths-of-silence

BY Richard Rohr OFM

When I first began to write this article, I thought to myself, “How do you promote something as vaporous as silence? It will be like a poem about air!” But finally I began to trust my limited experience, which is all that any of us have anyway.

I do know that my best writings and teachings have not come from thinking but, as Malcolm Gladwell writes in Blink, much more from not thinking. Only then does an idea clarify and deepen for me. Yes, I need to think and study beforehand, and afterward try to formulate my thoughts. But my best teachings by far have come in and through moments of interior silence – and in the “non-thinking” of actively giving a sermon or presentation.

Aldous Huxley described it perfectly for me in a lecture he gave in 1955 titled “Who Are We?” There he said, “I think we have to prepare the mind in one way or another to accept the great uprush or downrush, whichever you like to call it, of the greater non-self”. That precise language might be off-putting to some, but it is a quite accurate way to describe the very common experience of inspiration and guidance.

All grace comes precisely from nowhere – from silence and emptiness, if you prefer – which is what makes it grace. It is both not-you and much greater than you at the same time, which is probably why believers chose both inner fountains (John 7:38) and descending doves (Matthew 3:16) as metaphors for this universal and grounding experience of spiritual encounter. Sometimes it is an uprush and sometimes it is a downrush, but it is always from a silence that is larger than you, surrounds you, and finally names the deeper truth of the full moment that is you. I call it contemplation, as did much of the older tradition.

It is always an act of faith to trust silence, because it is the strangest combination of you and not-you of all. It is deep, quiet conviction, which you are not able to prove to anyone else – and you have no need to prove it, because the knowing is so simple and clear. Silence is both humble in itself and humbling to the recipient. Silence is often a momentary revelation of your deepest self, your true self, and yet a self that you do not yet know. Spiritual knowing is from a God beyond you and a God that you do not yet fully know. The question is always the same: “How do you let them both operate as one – and trust them as yourself?” Such brazenness is precisely the meaning of faith, and why faith is still somewhat rare, compared to religion.

And yes, such inner revelations are always beyond words. You try to sputter out something, but it will never be as good as the silence itself is. We just need the words for confirmation to ourselves and communication with others. So God graciously allows us words, and gives us words, but they are almost always a regression from the more spacious and forgiving silence. Words are a much smaller container. They are always an approximation. Surely some approximations are better than others, which is why we all like good novelists, poets, and orators. Yet silence is the only thing deep enough, spacious enough, and wide enough to hold all of the contradictions that words cannot contain or reconcile.

We need to “grab for words”, as we say, but invariably they tangle us up in more words to explain, clarify, and justify what we meant by the first words – and to protect us from our opponents. From there we often exacerbate many of our own problems by babbling on even further. In Matthew 6:7, Jesus had a word for heaping up empty phrases: paganism! Only those who love us will stay with us at that point, and often love will also tell us to stop talking – which is precisely why so many saints and mystics said that love precedes and prepares the way for all true knowing. Maybe silence is even another word for love?

Most of the time, “to make a name for ourselves” like the people building the tower of Babel, we multiply words and find ourselves saying more and more about less and less. This is sometimes called gossip, or just chatter. No wonder Yahweh “scattered them”, for they were only confusing themselves (Genesis 11:4-8). Really, they were already scattered people: scattered inside and out because there was no silence.

We are all forced to overhear cell phone calls in cafés, airports, and other public places today. People now seem to fill up their available time, reacting to their boredom – and their fear of silence – often by talking about nothing, or making nervous attempts at mutual flattery and reassurance. One wonders if the people on the other end of the line really need your too-easy comforts. Maybe they do, and maybe we all have come to expect it. But that is all we can settle for when there is no greater non-self, no gracious silence to hold all of our pain and our self-doubt. Cheap communication is often a substitute for actual communion.

Words are necessarily dualistic. That is their function. They distinguish this from that, and that’s good. But silence has the wonderful ability to not need to distinguish this from that! It can hold them together in a quiet, tantric embrace. Silence, especially loving silence, is always non-dual, and that is much of its secret power. It stays with mystery, holds tensions, absorbs contradictions, and smiles at paradoxes – leaving them unresolved, and happily so. Any good poet knows this, as do many masters of musical chords. Politicians, engineers, and most Western clergy have a much harder time.

Silence is what surrounds everything, if you look long enough. It is the space between letters, words, and paragraphs that makes them decipherable and meaningful. When you can train yourself to reverence the silence around things, you first begin to see things in themselves and for themselves. This “divine” silence is before, after, and between all events for those who see respectfully (to re-spect is “to see again”).

All creation is creatio ex nihilo – from “a trackless waste and an empty void” it all came (Genesis 1:2). But over this darkness God’s spirit hovered and “there was light” – and everything else too. So there must be something pregnant, waiting, and wonderful in such voids and darkness. God’s ongoing – and maybe only – job description seems to be to “create out of nothing”. We call it grace.

God follows this pattern, as do many saints, but most of us don’t. We prefer light (read: answers, certitude, moral perfection, and conclusions) but forget that it first came from a formless darkness. This denial of silence and darkness as good teachers emerged ever more strongly after the ironically named “Enlightenment” of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Our new appreciation of a kind of reason was surely good and necessary on many levels, but it also made us impatient and forgetful of the much older tradition of not knowing, unsaying, darkness, and silence. We decided that words alone would give us truth, not realising that all words are metaphors and approximations. The desert Jesus, Pseudo-Dionysius, The Cloud of Unknowing, and John of the Cross have not been ‘in’ for several centuries now, and we are much the worse for it.

The low point has now become religious fundamentalism, which ironically knows so little about the real fundamentals. We all fell in love with words, even those of us who said we believed that “the Word became flesh”. Words offer a certain light, but flesh is much better known in humble silence and waiting.

As a general spiritual rule, you can trust this one: The ego gets what it wants with words. The soul finds what it needs in silence. The ego prefers light – immediate answers, full clarity, absolute certitude, moral perfection, and undeniable conclusion – whereas the soul prefers the subtle world of darkness and light. And by that, of course, I mean a real interior silence, not just the absence of noise.

Robert Sardello, in his magnificent, demanding book Silence: The Mystery of Wholeness, writes that “Silence knows how to hide. It gives a little and sees what we do with it”. Only then will or can it give more. Rushed, manipulative, or opportunistic people thus find inner silence impossible, even a torture. They never get to the “more”. Wise Sardello goes on to say, “But in Silence everything displays its depth, and we find that we are a part of the depth of everything around us”. Yes, this is true.

When our interior silence can actually feel and value the silence that surrounds everything else, we have entered the house of wisdom. This is the very heart of prayer. When the two silences connect and bow to one another, we have a third dimension of knowing, which many have called spiritual intelligence or even “the mind of Christ” (1 Corinthians 2:10-16). No wonder that silence is probably the foundational spiritual discipline in all the world’s religions at the more mature levels. At the less mature levels, religion is mostly noise, entertainment, and words. Catholics and Orthodox Christians prefer theatre and wordy symbols; Protestants prefer music and endless sermons.

Probably more than ever, because of iPads, cell phones, billboards, TVs, and iPods, we are a toxically overstimulated people. Only time will tell the deep effects of this on emotional maturity, relationship, communication, conversation, and religion itself. Silence now seems like a luxury, but it is not so much a luxury as it is a choice and decision at the heart of every spiritual discipline and growth. Without it, most liturgies, Bible studies, devotions, ‘holy’ practices, sermons, and religious conversations might be good and fine, but they will never be truly great or life-changing – for ourselves or for others. They can only represent the surface; God is always found at the depths, even the depths of our sin and brokenness. And in the depths, it is silent.

It comes down to this: God is, and will always be, Mystery. Only a non-arguing presence, only a non-assertive self, can possibly have the humility and honesty to receive such mysterious silence.

When you can remain at peace inside of your own mysterious silence, you are only beginning to receive the immense “Love that moves the sun and the other stars”, as Dante so beautifully says – along with the immeasurable silent space between those trillions of stars, through which this Mystery is also choosing to communicate. Silence is space, and space beyond time. Those who learn to live there are spacious and timeless people. They make and leave room for all the rest of us.