Posts Tagged christian mysticism

When Glory Explodes the Forms: Doxology, Faith, and the Exorcism of Epistemology

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, New Nuggets, Theology on July 14, 2025

by John Stamps* Δόξα Πατρὶ καὶ Υἱῷ καὶ Ἁγίῳ Πνεύματι . . . I was paying attention in church last Sunday—really, I was. But when Fr. Nebojša intoned: “Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit, both now and always and unto the ages of ages,” a strange Platonic thought hijacked my brain. Socrates wouldn’t understand a word of this. For him, doxa meant “opinion.” The Father has an opinion? The Son too? And the Holy Spirit? Three divine “opinions”? Socrates would be horrified. In Book VI of The Republic, he blurts out: “Have you not observed that opinions (doxai) divorced from knowledge (episteme) are ugly things? The best of them are blind.” (506c) Already, he’d be reaching for the hemlock. But it gets worse. At St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church, when we recite the Nicene Creed—first in Greek, then in English—we fervently confess: Πιστεύω εἰς ἕνα Θεὸν Πατέρα παντοκράτορα . . . “I believe in one God, the Father Almighty.” Or, more provocatively—and more Christianly—“I put my trust in one God, the Father Almighty.” Once again, Socrates would be scandalized. Pistis? Mere belief? Conviction at best? And you’re going to stake that on ultimate reality? Pistis may rise above illusion (eikasia), but it’s still fog—not the clear light of truth. Surely the divine deserves better. Surely epistēmē—solid, demonstrable knowledge—is the true coin of the metaphysical realm. To entrust pistis with the highest things would be like trying to buy eternity with Monopoly money. For Plato, pistis belongs low on the Divided Line—just above eikasia (imagination and shadows), and well below epistēmē. It’s trust in what we can see and touch, but without glimpsing the hidden reality behind it—the invisible Forms that give things their true meaning. Pistis is for the unphilosophical. The half-blind. The cave-dwellers huddled in the cave who mistake sensible things for what is really real. But Christian theology flips the entire Platonic ladder upside down. From Doxa to Glory For Socrates, doxa means “opinion”—an unreliable, subjective mental state. But in Christian liturgy, doxa is glory: not mental conjecture but the radiant, overwhelming presence of the living God. Doxa is Moses taking off his shoes before the burning bush. Doxa is Moses descending Sinai with a face that glows because he got too close to raw holiness. Doxa is the Word made flesh, full of grace and truth, dwelling among us. Doxa is not conjecture. It’s encounter. Somewhere between the Hebrew Bible and the Septuagint, doxa got an upgrade. And this raises a linguistic and theological mystery: How did the Hebrew word כָּבוֹד (kavod—weight, substance, heaviness, splendor) become doxa (opinion) in Greek? The Septuagint translators had choices. And their choice changed Christian theology forever. From Pistis to Trust In the New Testament, pistis is not an epistemic crutch. It is relational trust, covenant loyalty, and a faithful response to a God who reveals Himself not in abstractions but in history, flesh, and self-giving love. Far from being a lower form of knowledge, pistis becomes the primary way humans recognize and respond to divine glory—a deeper, riskier kind of knowing, grounded in love, testimony, and encounter. For Socrates, by contrast, pistis was barely a step above guesswork—an uncritical belief in the physical world, just above imagination (eikasia) and far below true knowledge (epistēmē). It belonged to the realm of opinion (doxa) and was reserved for the half-blind dwellers in the cave. But in the New Testament, pistis becomes something far more daring. It echoes the Hebrew word emunah (אֱמוּנָה): steadfast trust, covenant faithfulness, unwavering reliability. Christian faith isn’t vague optimism. It’s not mere intellectual assent or rearranging our mental furniture. Pistis is not a foggy feeling or private conviction. It is existential trust. It is covenantal loyalty. It is Semper Fi!— our fidelity to the God who speaks, acts, and keeps His promises and our willingness to stake everything on His trustworthiness. Faith is stepping out onto the water like Peter because Jesus said, “Come.” Faith is betting everything on the God who delivered Israel from Pharaoh’s tyranny and raised Jesus from the dead. Or, as Robert Jenson once put it: “God is whoever raised Jesus from the dead, having before raised Israel from Egypt.” This is how Christians reliably identify and name God: by His acts of faithfulness. And pistis is our answering act of trust and faithfulness in return. From Eikasia to Icon Images are tricky. Plato had his reasons to be suspicious. He especially distrusted imitative images—whether in poetry, painting, or shadowplay—because they were seductive lies, copies of copies, that lured the soul away from truth and down into the flickering cave of illusion. Teenagers glued to their 300-DPI iPhone screens aren’t so different from the cave-dwellers in The Republic, staring at shadows on the wall, mistaking illusion for reality. That’s why Plato wanted the image-makers banished from the ideal city. For him, images were not innocent—they were propaganda, simulacra, distortions. In his metaphysics, images were the lowest of the low. But Christian theology tells a different story. Scripture gives us strong reasons to trust—not all images, but certain ones—as truth-bearing windows into reality. First, just look at yourself in the mirror—warts and all. You are the imago Dei. Look at your spouse, your children, your friends. Knock on your neighbor’s door with cookies or a bottle of wine. Hand $20 to a homeless person. Pray for—and forgive—your bitterest enemy. Why this exercise? Because every one of them is the imago Dei. They are the spitting image of God. This is where Christian theology begins: with the startling claim that human beings are made in the image and likeness of God. We bear the weight of glory. This image (εἰκών) is not falsehood. It is truth-bearing. It carries the imprint of the Creator. The image is not a pale copy—it participates in the reality it reflects. This image is a site where divine glory dwells. Second, when the Word became flesh, God’s image wasn’t entering alien territory. The Incarnation is not some bizarre intrusion into a world God otherwise keeps at arm’s length. It is the culmination of God’s long purpose for creation: that divine glory would dwell bodily within it. The Incarnation is no invasion. The kosmos belongs to the Lord, and the fullness thereof. Third, Jesus of Nazareth is the Image-Bearer par excellence. He looks just like us. That God was one of us is the scandal at the heart of the Christian confession. And yet . . . the One in whom all the fullness of God dwells (Colossians 2:9) looks so much like us that we don’t recognize Him. Familiarity breeds contempt and generates its own kind of blindness. Glory walks right past us wearing dusty sandals. But if we have eyes to behold the mystery, Jesus—crucified, risen, and ascended—is the true Image (εἰκών) of the invisible God (Colossians 1:15). Not a photocopy. Not a metaphor. Not a shadow. He is one of us—bone of our bone, flesh of our flesh. And yet He reveals God to us fully and truly. We Orthodox insist on this incarnational truth: images matter because the Image matters. To celebrate this, we wallpaper our churches with icons—not as decoration, but as theological proclamation. Icons are not aesthetic accessories. They are visual participation in divine reality. Icons reveal. They manifest. They make present. They proclaim what words alone cannot say. Why do we venerate icons? Because images, rightly ordered, are truth-bearing. Because the Image became flesh and dwelt among us. And because, through Christ, we too are being transfigured—from glory to glory—into the image of God. For us, seeing is not believing lies. Seeing is encountering glory. Epistemology Needs an Exorcism My old philosophy professor, Nicholas Wolterstorff, used to warn us: “Ever since Plato, the Western world has been haunted by the lure of certitude.” And he’s right. That ghost still lingers. We need an exorcism. We need to turn epistemology into doxology. Or more precisely: episteme-logos into doxo-logos. Once you’re bewitched by epistemology and the certainty it promises, it’s hard to break the spell. You start—and you end—by measuring all truth, including theological truth, by mental clarity, logical deduction, and timeless abstraction. But Trinitarian doxology and the Nicene Creed don’t just challenge Greek epistemology—they scandalize it. We can’t start with clear and distinct ideas. We must begin with faithful witness. We begin where we actually encounter the glory of God. The Father who speaks. The Son who acts. The Spirit who breathes. Three Persons. One God. Doxology—not detached speculation—is the engine that drives Christian theology. To the Greek philosophical mind—fixated on unchanging forms, impersonal absolutes, and epistemic certainty—this kind of God-talk sounds like theological madness. A God who speaks? Acts? Loves? Suffers? Raises the dead? So yes—we fumble and stumble for the right words. Apophatic theology rightly reminds us that God always exceeds our categories and language. But that doesn’t mean we stay silent. Christian speech begins in worship—yes, in doxology—and in the risky act of saying something true about the God who cannot be contained. Let the Platonists chase certainty . . . we behold glory. For the life of me, I still don’t fully understand how kavod—a word of weight and substance—became doxa, a word that once meant “opinion.” But the Septuagint translators had choices. And their choice opened the door for Christian theology to do something the ancient philosophers never saw coming. Faithful God-talk begins not with control, but with wonder. Not with clarity, but with trust. Not with epistemic mastery, but with doxology. We speak because God has spoken. We bear witness because doxa showed up in history, and refused to stay abstract. We dare to name the Unnameable because the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth . . . and we beheld His glory. Let the Platonists chase their Forms, the Cartesians polish their clear and distinct ideas, and the positivists flatten everything into data. And yes, let the American Fundamentalists obsess over the inerrancy of the original autographs—those long-lost parchments that somehow guarantee perfect doctrine, if only we squint hard enough. Scripture, for them, isn’t the living voice that calls us into communion, but a cosmic answer key dropped from heaven. The lure of certitude is still a mirage. We will not lose our nerve. We will render doxa to the God who acts— Who speaks, Who raises the dead, Who walks through our kosmos with dusty feet and scandalous grace. . . . καὶ νῦν καὶ ἀεὶ καὶ εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων. Ἀμήν.  * * *John Stamps is Senior Technical Writer at Guidewire Software in San Mateo, California. He holds a BA in Greek from Abilene Christian University, an MDiv from Princeton Theological Seminary, and pursued further study in the philosophy of religion at Yale Divinity School—just long enough to accrue debt and existential questions. He attends St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church in San Jose, is married to the long-suffering Shelly Houston Stamps, plays mediocre tennis with misplaced confidence, and speaks Spanish that routinely scandalizes native speakers and small children. |

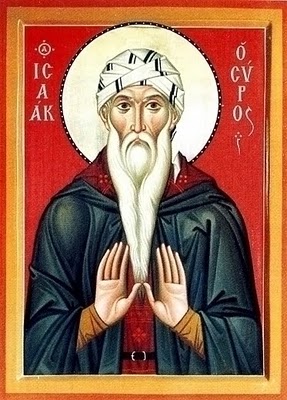

Isaac of Nineveh: “In love did He bring the world into existence…”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, Heaven and Hell, Monasticism, Patristic Pearls, Universal Restoration (Apokatastasis) on June 11, 2025

St. Isaac of Nineveh – 7th century ascetic and mystic, born in modern-day Qatar, was made Bishop of Nineveh between 660-680. Especially influential in the Syriac tradition, Isaac has had a great influence in Russian culture, impacting the works of writers like Dostoyevsky.

Isaac composed dozens of homilies that he collected into seven volumes on topics of spiritual life, divine mysteries, judgements, providence, and more. Today, these seven volumes have survived in five Parts, titled from the First Part to the Fifth Part. Only the First Part was widely known outside of Aramaic speaking communities until 1983.

Some scholars argue that Isaac’s views from the Second Part appear to confirm earlier claims that Isaac advocated for universal reconciliation, or apokatastasis.

“What profundity of richness, what mind and exalted wisdom is God’s! What compassionate kindness and abundant goodness belongs to the Creator! …

In love did He bring the world into existence; in love does He guide it during this its temporal existence; in love is He going to bring it to that wondrous transformed state, and in love will the world be swallowed up in the great mystery of Him who has performed all these things; in love will the whole course of the governance of creation be finally comprised.” (II.38.1-2)

Isaac the Syrian, The Second Part, trans. Sebastian Brock (Peeters: Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, 1995).

The Greek East – …sunk…in a sleep of traditionalism… and ethno-phyletism

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church on May 2, 2025

This is the bad news:

Hyper-Traditionalism

“It is probable enough that this widespread ascendancy of Augustinianism would not have maintained itself so long but for the utter decay of the Greek Church, under that debasing servility of the Church to palace intrigue, which is known as Byzantinism. It has been truly said that, just as the rise of scholasticism in the West was an attempt of the Latins to Hellenize, and so let a breath of philosophic thought pass over the stagnant morass of dead dogmatism; so, on the other hand, Greek theology in the age of its decline showed a tendency to Latinise, and to fall away from the high intuitional view of spiritual realities, by mixing its gold with the clay of legal conceptions. The result of this falling away of Greek theology into Byzantinism, by the adoption of a magical external type of ceremonial religion, has been that Reformers have ceased to look any longer for new light from the East, and have steadily set their faces to the far West. We have ceased to think of the church of the future as a revised orthodox Church… This is only what we may expect as long as the East continues sunk, as at present, in a sleep of traditionalism.”

J.B. Heard, 1893.

Ethno-phyletism

The above entry was written in 1893 and is as true today as it was then. Coincidentally, 21 years before Heard wrote this, the Council of Constantinople of 1872 dealt with the growing problem within Orthodoxy of phyletism, specifically ethno-phyletism, which comes from the Greek: “Ethno-Phyle-Tismos“, and can be accurately translated as “national tribalism”.

Phyletism relates to the problem of separating the unity of the one Orthodox Church into any number of competitive national, linguistic, racial or ethnic Churches. The problem arises both in the countries where Orthodoxy is the dominant religion (e.g. Romania, Russia, Bulgaria, Greece), but also in countries where Orthodoxy is represented by different countries that have immigrants (diaspora) there (e.g. UK, France, Canada, US). The term ethno-phyletism promotes the idea that a local autocephalous (self-governing) church should not be based on a local criterion, but on a national, ethnic, racial, or linguistic one. The 1872 Council condemned “phyletist nationalism” as a modern ecclesial heresy: the church was not to be confused with the destiny of a single nation or a single race.

In the United States, most Eastern Orthodox parishes as well as jurisdictions are ethnocentric, that is, focused on serving an ethnic community that has immigrated from overseas (e.g., the Greeks, Russians, Romanians, Finns, Serbs, Arabs, etc.).

In June 2008, Metropolitan Jonah of the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) delivered a talk on “Episcopacy, Primacy, and the Mother Churches: A Monastic Perspective” at the Conference of the Fellowship of St. Alban and St. Sergius at St. Vladimir’s Theological Seminary.

He said:

“The problem is not so much the multiple overlapping jurisdictions, each ministering to diverse elements of the population. This could be adapted as a means of dealing with the legitimate diversity of ministries within a local or national Church. The problem is that there is no common expression of unity that supersedes ethnic, linguistic and cultural divisions: there is no synod of bishops responsible for all the churches in America, and no primacy or point of accountability in the Orthodox world with the authority to correct such a situation.”

Metropolitan Jonah was forced to resign in 2012.

In 1872, the problem was Bulgaria. In 2019, the problem was Ukraine. In 2025, the problem is the US, UK, France, and others.

Same problems, 150+ years later; the Church’s behavior is virtually identical to most any established worldly institution.

The good news is: It’s temporary!

Yes, it’s temporary. All the problems discussed are typical of worldly cultural institutions. They will pass away in time.

I know the orthodox church has had challenges building a suitable institutional infrastructure since the mid-fourth century; it’s had challenges being partnered with powerful worldly empire; it had internal struggles with Western Patriarchal obsession with hierarchical administrative control; it dealt with numerous violent Muslim crises; and resisted Western cultural and political pressures… the list could go on and on.

And yes, myopic focus on tradition and insular, triumphalist ethno-phyletism needs to be dealt with.

But, the Orthodox church is still the church of Justin, Clement, Origen, Athanasius, and the Cappadocians; it is the source, repository and guardian of inspired universal Logos theology, applicable to all of mankind as The Way to union with God. And remember, church, “evangelism” is not a Protestant word or idea; they just borrowed it (from you!). εὐαγγέλιον (euaggelion), The Good News. You remember, right? Goes right along with κήρυγμα (kerygma), the apostolic proclamation; accompanied by signs and wonders (σημεῖα καὶ τέρατα). All of this is part of the Orthodox Tradition. It’s right there, hidden under your pillow!

Wake up, church!

Athanasius of Alexandria on the Logos

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls, The Logos Doctrine (series) on April 15, 2025

Athanasius of Alexandria (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, was a Christian theologian and the 20th patriarch of Alexandria. In 325, at age 27, Athanasius began his leading role against the Arians as a deacon and assistant to Bishop Alexander of Alexandria during the First Council of Nicaea.

Excerpted from: The Complete Works of St. Athanasius, Against the Heathen, Part 3, pp., 40-44.

40. The rationality and order of the Universe proves that it is the work of the Reason or Word of God.

Who then might this Maker be? For this is a point most necessary to make plain, lest, from ignorance with regard to him, a man should suppose the wrong maker, and fall once more into the same old godless error, but I think no one is really in doubt about it. For if our argument has proved that the gods of the poets are no gods, and has convicted of error those that deify creation, and in general has shown that the idolatry of the heathen is godlessness and impiety, it strictly follows from the elimination of these that the true religion is with us, and that the God we worship and preach is the only true One, Who is Lord of Creation and Maker of all existence.

2. Who then is this, save the Father of Christ, most holy and above all created existence , Who like an excellent pilot, by His own Wisdom and His own Word, our Lord and Saviour Christ, steers and preserves and orders all things, and does as seems to Him best? But that is best which has been done, and which we see taking place, since that is what He wills; and this a man can hardly refuse to believe.

3. For if the movement of creation were irrational, and the universe were borne along without plan, a man might fairly disbelieve what we say. But if it subsist in reason and wisdom and skill, and is perfectly ordered throughout, it follows that He that is over it and has ordered it is none other than the [reason or] Word of God.

4. But by Word I mean, not that which is involved and inherent in all things created, which some are wont to call the seminal principle, which is without soul and has no power of reason or thought, but only works by external art, according to the skill of him that applies it—nor such a word as belongs to rational beings and which consists of syllables, and has the air as its vehicle of expression—but I mean the living and powerful Word of the good God, the God of the Universe, the very Word which is God [ John 1:1 ], Who while different from things that are made, and from all Creation, is the One own Word of the good Father, Who by His own providence ordered and illumines this Universe.

5. For being the good Word of the Good Father He produced the order of all things, combining one with another things contrary, and reducing them to one harmonious order. He being the Power of God and Wisdom of God causes the heaven to revolve, and has suspended the earth, and made it fast, though resting upon nothing, by His own nod. Illumined by Him, the sun gives light to the world, and the moon has her measured period of shining. By reason of Him the water is suspended in the clouds; the rains shower upon the earth, and the sea is kept within bounds, while the earth bears grasses and is clothed with all manner of plants.

6. And if a man were incredulously to ask, as regards what we are saying, if there be a Word of God at all , such an one would indeed be mad to doubt concerning the Word of God, but yet demonstration is possible from what is seen, because all things subsist by the Word and Wisdom of God, nor would any created thing have had a fixed existence had it not been made by reason, and that reason the Word of God, as we have said.

41. The Presence of the Word in nature necessary, not only for its original Creation, but also for its permanence.

But though He is Word, He is not, as we said, after the likeness of human words, composed of syllables; but He is the unchanging Image of His own Father. For men, composed of parts and made out of nothing, have their discourse composite and divisible. But God possesses true existence and is not composite, wherefore His Word also has true Existence and is not composite, but is the one and only-begotten God , Who proceeds in His goodness from the Father as from a good Fountain, and orders all things and holds them together.

2. But the reason why the Word, the Word of God, has united Himself with created things is truly wonderful, and teaches us that the present order of things is none otherwise than is fitting. For the nature of created things, inasmuch as it is brought into being out of nothing, is of a fleeting sort, and weak and mortal, if composed of itself only. But the God of all is good and exceeding noble by nature,— and therefore is kind. For one that is good can grudge nothing : for which reason he does not grudge even existence, but desires all to exist, as objects for His loving-kindness.

3. Seeing then all created nature, as far as its own laws were concerned, to be fleeting and subject to dissolution, lest it should come to this and lest the Universe should be broken up again into nothingness, for this cause He made all things by His own eternal Word, and gave substantive existence to Creation, and moreover did not leave it to be tossed in a tempest in the course of its own nature, lest it should run the risk of once more dropping out of existence ; but, because He is good He guides and settles the whole Creation by His own Word, Who is Himself also God, that by the governance and providence and ordering action of the Word, Creation may have light, and be enabled to abide always securely. For it partakes of the Word Who derives true existence from the Father, and is helped by Him so as to exist, lest that should come to it which would have come but for the maintenance of it by the Word,— namely, dissolution— ” for He is the Image of the invisible God, the first-born of all Creation, for through Him and in Him all things consist, things visible and things invisible, and He is the Head of the Church, ” as the ministers of truth teach in their holy writings.

42. This function of the Word described at length.

The holy Word of the Father, then, almighty and all-perfect, uniting with the universe and having everywhere unfolded His own powers, and having illumined all, both things seen and things invisible, holds them together and binds them to Himself, having left nothing void of His own power, but on the contrary quickening and sustaining all things everywhere, each severally and all collectively; while He mingles in one the principles of all sensible existence, heat namely and cold and wet and dry, and causes them not to conflict, but to make up one concordant harmony.

2. By reason of Him and His power, fire does not fight with cold nor wet with dry, but principles mutually opposed, as if friendly and brotherly combine together, and give life to the things we see, and form the principles by which bodies exist. Obeying Him, even God the Word, things on earth have life and things in the heaven have their order. By reason of Him all the sea, and the great ocean, move within their proper bounds, while, as we said above, the dry land grows grasses and is clothed with all manner of diverse plants. And, not to spend time in the enumeration of particulars, where the truth is obvious, there is nothing that is and takes place but has been made and stands by Him and through Him, as also the Divine [ John 1:1 ] says, ” In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God; all things were made by Him, and without Him was not anything made. ”

3. For just as though some musician, having tuned a lyre, and by his art adjusted the high notes to the low, and the intermediate notes to the rest, were to produce a single tune as the result, so also the Wisdom of God, handling the Universe as a lyre, and adjusting things in the air to things on the earth, and things in the heaven to things in the air, and combining parts into wholes and moving them all by His beck and will, produces well and fittingly, as the result, the unity of the universe and of its order, Himself remaining unmoved with the Father while He moves all things by His organising action, as seems good for each to His own Father.

4. For what is surprising in His godhead is this, that by one and the same act of will He moves all things simultaneously, and not at intervals, but all collectively, both straight and curved, things above and beneath and intermediate, wet, cold, warm, seen and invisible, and orders them according to their several nature. For simultaneously at His single nod what is straight moves as straight, what is curved also, and what is intermediate, follows its own movement; what is warm receives warmth, what is dry dryness, and all things according to their several nature are quickened and organised by Him, and He produces as the result a marvellous and truly divine harmony.

43. Three similes to illustrate the Word’s relation to the Universe.

And for so great a matter to be understood by an example, let what we are describing be compared to a great chorus. As then the chorus is composed of different people, children, women again, and old men, and those who are still young, and, when one, namely the conductor, gives the sign, each utters sound according to his nature and power, the man as a man, the child as a child, the old man as an old man, and the young man as a young man, while all make up a single harmony;

2. or as our soul at one time moves our several senses according to the proper function of each, so that when some one object is present all alike are put in motion, and the eye sees, the ear hears, the hand touches, the smell takes in odour, and the palate tastes—and often the other parts of the body act too, as for instance if the feet walk;

3. or, to make our meaning plain by yet a third example, it is as though a very great city were built, and administered under the presence of the ruler and king who has built it; for when he is present and gives orders, and has his eye upon everything, all obey; some busy themselves with agriculture, others hasten for water to the aqueducts, another goes forth to procure provisions—one goes to senate, another enters the assembly, the judge goes to the bench, and the magistrate to his court. The workman likewise settles to his craft, the sailor goes down to the sea, the carpenter to his workshop, the physician to his treatment, the architect to his building; and while one is going to the country, another is returning from the country, and while some walk about the town others are going out of the town and returning to it again: but all this is going on and is organised by the presence of the one Ruler, and by his management:

4. in like manner then we must conceive of the whole of Creation, even though the example be inadequate, yet with an enlarged idea. For with the single impulse of a nod as it were of the Word of God, all things simultaneously fall into order, and each discharge their proper functions, and a single order is made up by them all together.

44. The similes applied to the whole Universe, seen and unseen.

For by a nod and by the power of the Divine Word of the Father that governs and presides over all, the heaven revolves, the stars move, the sun shines, the moon goes her circuit, and the air receives the sun’s light and the æther his heat, and the winds blow: the mountains are reared on high, the sea is rough with waves, and the living things in it grow, the earth abides fixed, and bears fruit, and man is formed and lives and dies again, and all things whatever have their life and movement; fire burns, water cools, fountains spring forth, rivers flow, seasons and hours come round, rains descend, clouds are filled, hail is formed, snow and ice congeal, birds fly, creeping things go along, water-animals swim, the sea is navigated, the earth is sown and grows crops in due season, plants grow, and some are young, some ripening, others in their growth become old and decay, and while some things are vanishing others are being engendered and are coming to light.

2. But all these things, and more, which for their number we cannot mention, the worker of wonders and marvels, the Word of God, giving light and life, moves and orders by His own nod, making the universe one. Nor does He leave out of Himself even the invisible powers; for including these also in the universe inasmuch as he is their maker also, He holds them together and quickens them by His nod and by His providence. And there can be no excuse for disbelieving this.

3. For as by His own providence bodies grow and the rational soul moves, and possesses life and thought, and this requires little proof, for we see what takes place—so again the same Word of God with one simple nod by His own power moves and holds together both the visible universe and the invisible powers, allotting to each its proper function, so that the divine powers move in a diviner way, while visible things move as they are seen to do. But Himself being over all, both Governor and King and organising power, He does all for the glory and knowledge of His own Father, so that almost by the very works that He brings to pass He teaches us and says, ” By the greatness and beauty of the creatures proportionably the maker of them is seen [Wisdom 13:5].”

Note: In the above text, when you see “Word”, substitute the Greek word “Logos”. There is no English word that spans the same conceptual range.

Apophatic and Cataphatic Theology: An Issue of Emphasis and Balance

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Contemplative Prayer (series), Ekklesia and church, Essence and Energies (series), First Thoughts, Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, The Cappadocians, Theology on April 6, 2025

Overview

Apophatic and Cataphatic are two terms used in theology to describe different approaches to understanding God. The Eastern Orthodox and Latin West each use both types. The issue comes down to one of emphasis and balance: The Orthodox East is overwhelmingly Apophatic in approach, while the Latin West is predominantly Cataphatic.

Definitions

Apophatic theology (from Greek: ἀπόφημι apophēmi, meaning “to deny”) uses “negative” terminology to indicate what it is believed the divine is not. It means emptying the mind of words and ideas and simply resting in the presence of God. Apophatic prayer is prayer that occurs without words, images, or concepts. This approach to prayer regards silence, stillness, unknowing and even darkness as doorways, rather than obstacles, to communication with God. Apophatic theology relies primarily on experience and revelation.

Cataphatic theology (from the Greek word κατάφασις kataphasis meaning “affirmation”) uses “positive” terminology to describe or refer to the divine, i.e. terminology that describes or refers to what the divine is believed to be. Cataphatic prayer is prayer that speaks thoroughly, intensively, or positively of God: prayer that uses words, images, ideas, concepts, and the imagination to relate to God. Cataphatic theology relies heavily on logic and reason.

Background

Apophatic theology—also known as negative theology or via negativa—is a theology that attempts to describe God by negation. In Orthodox Christianity, Apophatic theology is based on the assumption that God’s essence is unknowable or ineffable and on the recognition of the inadequacy of human language to describe God. The Apophatic tradition in Orthodoxy is balanced with Cataphatic theology (positive theology) via belief in the Incarnation and the self-revealed energies of God, through which God has revealed himself in the person of Jesus Christ. However, Apophatic theology is the dominant traditional Eastern paradigm of an experiential, revealed theology, intimately linking doctrine with contemplation through purgation (catharsis), illumination (theoria), and union (theosis).

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – 215) was an early proponent of Apophatic theology with elements of Cataphatic. Clement holds that God is unknowable, although God’s unknowability, concerns only his essence, not his energies, or powers. According to Clement’s writings, the term theoria develops further from a mere intellectual “seeing” toward a spiritual form of contemplation. Clement’s Apophatic theology or philosophy is closely related to this kind of theoria and the “mystic vision of the soul.” For Clement, God is both transcendent in essence and immanent in self-revelation.

The Cappadocian Fathers (Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus (4th century)) were early exemplars of this Apophatic theology. They stated that mankind can acquire an incomplete knowledge of God in his attributes, positive and negative, by reflecting upon and participating in his self-revelatory operations (energeia). But, the essence of God is completely unknowable.

A century later Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (late 5th century) in his short work Mystical Theology, first introduced and explained what came to be known as Apophatic or negative theology.

Maximus the Confessor (7th century) maintained that the combination of Apophatic theology and hesychasm—the practice of silence and stillness—made theosis or union with God possible.

John of Damascus (8th century) employed Apophatic theology when he wrote that positive (cataphatic) statements about God reveal “not the nature, but the things around the nature.”

All in all, Apophatic theology remains crucial to much of the theology in Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The opposite tends to be true in Western Latin Christianity, with a few notable exceptions to this rule.

Cataphatic theology

In the Latin West a heavily Cataphatic theology, or via positiva, developed, which remains today in most forms of Western Christianity. This type of Cataphatic theology is based on using human reason to make positive statements about the nature of God. It slowly developed from the 5th to the 11th century, emerging as Scholasticism in the Medieval Period (11th-17th centuries). (see entries for Anselm and Thomas Aquinas, below)

Augustine of Hippo (354–430) significantly influenced scholasticism, emphasizing the integration of faith and reason. His ideas laid the groundwork for later Scholastic thinkers who sought to reconcile Christian theology with classical philosophy, particularly through dialectic reasoning. Augustine’s doctrines of the filioque, original sin, the doctrine of grace, and predestination found little support outside of the Western Roman Church. Within the Western Latin church, ‘Augustinianism’ dominated early theology.

Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033 – 1109) is widely considered the father of Scholasticism, endeavoring to render Christian tenets of faith, traditionally taken as a revealed truth, as a rational system. Scholasticism prescribed that Aristotelian dialectic reason be used in the elucidation of spiritual truth and in defense of the dogmas of Faith.

Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225 – 7 March 1274) reflects the mature emergence of this new medieval Scholastic paradigm, which promoted the use of formal intellectual reason, putting it at odds with the predominantly Eastern revealed tradition of hesychastic contemplation. Aquinas’ Summa Theologica (1265–1274), is considered to be the pinnacle of Medieval Scholastic Christian philosophy and theology. The resulting ‘Thomism’ remains the foundation of contemporary Western Latin theology.

Early References to Apophatic Darkness in Christian Mysticism

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls, Theology on April 3, 2025

Gregory of Nyssa – from The life of Moses (ca. AD 380)

“luminous darkness” (or dazzling darkness)

(λαµπρός γνόφος)

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite – from The Mystical Theology (ca. AD 500)

“in the brilliant darkness of a hidden silence”

(τὸν ὑπέρφωτον τῆς σιγῆς γνόφον)

“the ray of divine darkness, which is above everything that is”

(τὸν ὑπερούσιον τοῦ θείου σκότους ἀκτῖνα)

Maximus the Confessor – from Two Hundred Chapters on Theology (ca. AD 633), 1.84, 1.85

“The great Moses, having pitched his tent outside the camp, that is, having established his will and intellect outside visible realities, begins to worship God; and having entered the dark cloud, the formless and immaterial place of knowledge, he remains there, performing the holiest rites.”

(Μωϋσῆς ὁ μέγας ἔξω τῆς παρεμβολῆς πηξάμενος ἑαυτοῦ τὴν σκηνήν, τουτέστι, τὴν γνώμην καὶ τὴν διάνοιαν ἱδρυσάμενος ἔξω τῶν ὁρωμένων, προσκυνεῖν τὸν Θεὸν ἄρχεται· καὶ εἰς τὸν γνόφον εἰσελθών, τὸν ἀειδῆ καὶ ἄϋλον τῆς γνώσεως τόπον, ἐκεῖ μένει τὰς ἱερωτάτας τελούμενος τελετάς.)

“The dark cloud is the formless, immaterial, and incorporeal condition containing the paradigmatic knowledge of beings; he who has come to be inside it, just like another Moses, understands invisible realities in a mortal nature; having depicted the beauty of the divine virtues in himself through this state, like a painting accurately rendering the representation of the archetypal beauty, he descends, offering himself to those willing to imitate virtue, and in this shows both love of humanity and freedom from envy of the grace of which he had partaken.”

(Ὁ γνόφος ἐστὶν ἡ ἀειδὴς καὶ ἄϋλος καὶ ἀσώματος κατάστασις, ἡ τὴν παραδειγματικὴν τῶν ὄντων ἔχουσα γνῶσιν· ἐν ᾗ ὁ γενόμενος ἐντός, καθάπερ τις ἄλλος Μωϋσῆς, φύσει θνητῇ κατανοεῖ τὰ ἀθέατα, δι᾿ ἧς τῶν θείων ἀρετῶν ἐν ἑαυτῷ ζωγραφήσας τὸ κάλλος, ὥσπερ γραφὴν εὐμιμήτως ἔχουσαν τοῦ ἀρχετύπου κάλλους τὸ ἀπεικόνισμα, κάτεισιν, ἑαυτὸν προβαλλόμενος τοῖς βουλομένοις μιμεῖσθαι τὴν ἀρετήν, καὶ ἐν τούτῳ δεικνύς, ἧς μετειλήφει χάριτος, τὸ φιλάνθρωπόν τε καὶ ἄφθονον.)

The Apostle Paul: Radical, Conservative, or Reactionary?

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, Theology, Women in Early Christianity on March 21, 2025

The Apostle Paul is a controversial figure. More than half of the New Testament is written by him, about him, or in his name. There is a general consensus among contemporary scholars that the Apostle Paul did not write all 13 New Testament letters attributed to him.

Modern scholarship attributes seven of Paul’s 13 canonical letters as unquestionably authentic:

- Romans,

- Galatians,

- I Corinthians,

- II Corinthians,

- I Thessalonians,

- Philippians, and

- Philemon

Three others are generally considered deutero or (pseudo) – Pauline and are Pauline in theology, with a couple of notable exceptions, but are different in style and much more mainline and conservative in tone than the undisputed letters. They were probably written in the generation after Paul’s death by people very familiar with his teaching. The deutero (or pseudo)-Pauline letters are:

- Colossians,

- Ephesians, and

- II Thessalonians

The last three, the “Pastoral Letters”, are largely considered pseudepigrapha (a bible scholar’s politically-correct term for “forgery”) and were probably written around the beginning of the 2nd century and exhibit patriarchal, sexist, and reactionary social attitudes one would expect of an entrenched Greco-Roman cultural institution (exactly what the early Church was becoming by that time).1,2 The pseudepigraphical letters are:

- I Timothy,

- II Timothy, and

- Titus

What follows are estimates of the percentages of biblical scholars who reject Paul’s authorship of the six books in question:

- 2 Thessalonians = 50 percent;

- Colossians = 60 percent;

- Ephesians = 70 percent;

- 2 Timothy = 80 percent;

- 1 Timothy and Titus = 90 percent.2

In addition to judgments about entire letters, scholars also question the authorship of certain passages in the undisputed letters. Post-Pauline texts are those alleged to have been inserted into a letter after its composition and are generally called scribal “interpolations”.

Among the passages that some scholars label as interpolations are:

- Romans 5:5-7, 13:1-7, 16:17-20, 16:25-27;

- 1 Corinthians 4:6b, 11:2-16, 14:33b-35 or 36;

- 2 Corinthians 6:14-7:1; and

- 1 Thessalonians 2:14-16.2,3

Given the above, one could argue that there are really three “Pauls” in the New Testament:

- The Radical Paul of the seven undisputed authentic letters

- The Conservative Paul of the three deutero-Pauline letters

- The Reactionary Paul of the three pseudepigraphical Pastoral Letters

___________________________________________________________

- The First Paul, Reclaiming the Radical Visionary Behind the Church’s Conservative Icon, By Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan , 2009 HarperCollins, NY, NY

- Apostle of the Crucified Lord, A Theological Introduction to Paul & His Letters, by Michael J. Gorman, 2004 Wm. B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI / Cambridge, UK

- The Authentic Letters of Paul, A New Reading of Paul’s Rhetoric and Meaning, by Arthur J. Dewey, Roy W. Hoover, Lane C. Mc Gaughy, and Daryl D. Schmidt, 2010 Polebridge Press, Salem, OR

St. Justin Martyr: Synthesizing Philosophy and Faith; the ‘Spermatikos Logos’

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls, The Logos Doctrine (series), Theology on March 17, 2025

St. Justin Martyr (100 -166 A.D.), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian philosopher and apologist (Defender of the Faith). He was a Samaritan, born in Flavia Neapolis, Palestine, located near Jacob’s well (cf., John 4). From an early age, he studied Stoic and Platonic philosophers. At the age of 32, he converted to Christianity in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), possibly in Ephesus. Around the age of 35, he became an iterant preacher, moving from city to city in the Roman Empire, in an effort to convert educated pagans to the faith. Eventually, he ended up in Rome and spent a considerable amount of time there, debating and defending the faith. Of all his writings, only three survive: First Apology, Second Apology, and Dialogue with Trypho. St. Justin Martyr was scourged and beheaded in Rome in AD 166, under the reign of Marcus Aurelius, along with six of his followers.

Unlike Tertullian (a 2nd century Roman Carthaginian Christian author), who was opposed to Greek philosophy and viewed it as a dangerous pagan influence on Christianity, Justin Martyr viewed Greek philosophy in a more positive and optimistic light. He believed that Christianity both corrected and perfected philosophy.

While Tertullian refused to build a bridge between faith and philosophy, Justin Martyr was, on the other hand, eager to build a bridge between the two – and the name of that bridge was Logos*.

Logos, a central concept in ancient Greek philosophy, represents the divine reason or rational principle that governs the universe. The concept of Logos predates philosophical Stoicism. However, the Stoics, beginning with Zeno of Citium in the 3rd century BC, developed it into a cornerstone of their philosophical system. This Greek term, often translated as “word,” “reason,” or “plan,” is fundamental to understanding Stoic philosophical cosmology and ethics. In Stoic thought, Logos is not just an abstract principle but an active, generative force that permeates all of reality. To the Stoics, Logos represented:

• Universal Reason: Logos as the rational structure of the cosmos

• Divine Providence: The idea that the universe is governed by a benevolent plan

• Natural Law: Logos as the source of moral and physical laws

• Human Rationality: The belief that human reason is a fragment of the universal Logos

After John the Gospel Writer declared Christ to be the Logos in the prologue to his Gospel (cf., John 1, “In the beginning was the Logos…”) in about AD 90, the idea of Christ as Logos reached full bloom in the second century A.D., thanks to Justin Martyr and other early like-minded Christian philosophers.

Justin embraced the term “Logos” because it was familiar to Christians and non-Christians alike. Justin, in discussing the Logos, uses the expression, ζωτικόν πνεύμα (zotikon pneuma), vital spirit, which imparted reason as well as life to the soul. Justin understood this ζωτικόν πνεύμα as the divine principle in man. For Justin, it is a participation in the very life of the Logos. Therefore, he calls it the σπερματικόσ λόγοσ (spermatikos logos), the ‘seed of the word’, or reason in man.

This was a powerful tool in the hands of apologists like Justin. For by “Christianizing” Greek philosophy and literature, and deeming it a forerunner to Christ, the Christian apologists could easily counter the claims of the pagans who maintained that the Greeks beat the Christians to the punch. After all, the pagans said, the truths that the Christians were proclaiming as new were being taught by Greek philosophers years (read: centuries) before.

Justin maintained that the whole of Logos resided in Christ, but that all people, regardless of time or religion, contained these “seeds” of logos. Justin states,

“We have been taught that Christ is the first-born of God, and we have declared above that He is the Word [Logos] of whom every race of men were partakers; and those who lived reasonably are Christians, even though they have been thought atheists; as, among the Greeks, Socrates and Heraclitus, and men like them;” (First Apology, Chapt. 46)

Justin declared that even the pre-Christian philosophers who thought, spoke, and acted rightly did so because of the presence of the spermatikos logos in their hearts. To Justin, there is only one Logos that sows the seeds of spiritual and moral illumination in the hearts of human beings. Justin applied the spermatikos logos to explain that Christ, as the Logos, was in the world before his Incarnation, from the beginning of time, sowing the seeds of the logos in the hearts of all people. In this way, Christ united faith and philosophy. To Justin, Christ is the ultimate source of all wisdom and knowledge, even among pagans. Justin writes:

“For each man spoke well in proportion to the share he had of the spermatic word [spermatikos logos], seeing what was related to it… Whatever things were rightly said among all men, are the property of us Christians… For all the writers were able to see realities darkly through the sowing of the implanted word that was in them.” (Second Apology, Chap. 13)

According to Justin, some virtuous pagans recognized the spermatikos logos within themselves and cultivated it to a large extent. These became the great thinkers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Some, in the manner of Christ, like Socrates and Heraclitus, were even hated and persecuted for their beliefs and actions. Justin tells us the following:

“And those of the Stoic school — since, so far as their moral teaching went, they were admirable, as were also the poets in some particulars, on account of the seed of reason [the Logos] implanted in every race of men — were, we know, hated, and put to death — Heraclitus for instance, and, among those of our own time…others.” (Second Apology, Chap. 8)

People who came before the Incarnation of Jesus Christ all had the spermaticos logos, the “seed” of the Logos, implanted in them. Those Christians who came after the incarnation and resurrection of Jesus Christ had full access to all of Christ, the complete Logos. Those who came before saw through a glass darkly, but those who embrace Jesus Christ in the Christian era experience the fullness of revelation—faith and philosophy synthesized via Christ as Logos.

The Logos reveals all of God because He is God and we Christians had all the fullness of Logos because we had the revelation of Jesus Christ. The pagans did not have that. They had the spermatikos logos, but not the resurrected Christ.

Justin’s Logos was Jesus Christ himself portrayed against the backdrop of the Old Testament “Word of God” and Greek philosophy.

Contemporary Christians can easily agree with Justin Martyr that all people have within them the seeds of the Logos, the spermatikos logos. It is another way of saying that we all are created in the image of God and have an inherent knowledge of him and desire for Him.

Justin Martyr clearly represents an early, inclusive, universal Christianity encompassing all persons and religions; a time before the Church developed into an exclusive, parochial, competitive, religious institution.

Regardless of Tertullian’s fear that synthesizing faith with philosophy would “Hellenize” Christianity, Justin’s efforts ended up doing the precise opposite; faith ended up “Christianizing” Hellenism.

* “In Latin, such is the poverty of the language, there is no term at all equivalent to the Logos.” – John B. Heard. The same is true of English.

Isaac of Nineveh: On Universal Restoration

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Heaven and Hell, Patristic Pearls, Universal Restoration (Apokatastasis) on March 9, 2025

St. Isaac of Nineveh – 7th century ascetic and mystic, born in modern-day Qatar, was made Bishop of Nineveh between 660-680. Especially influential in the Syriac tradition, Isaac has had a great influence in Russian culture, impacting the works of writers like Dostoyevsky.

Isaac composed dozens of homilies that he collected into seven volumes on topics of spiritual life, divine mysteries, judgements, providence, and more. Today, these seven volumes have survived in five Parts, titled from the First Part to the Fifth Part. Only the First Part was widely known outside of Aramaic speaking communities until 1983.

Some scholars argue that Isaac’s views from the Second Part appear to confirm earlier claims that Isaac advocated for universal reconciliation, or apokatastasis.

“God will not abandon anyone.” [First Part, Chap. 5]

“There was a time when sin did not exist, and there will be a time when it will not exist.” [First Part, Chap. 26]

“As a handful of sand thrown into the ocean, so are the sins of all flesh as compared with the mind of God; as a fountain that flows abundantly is not dammed by a handful of earth, so the compassion of the Creator is not overcome by the wickedness of the creatures… If He is compassionate here, we believe that there will be no change in Him; far be it from us that we should wickedly think that God could not possibly be compassionate; God’s properties are not liable to variations as those of mortals… What is hell as compared with the grace of resurrection? Come and let us wonder at the grace of our Creator.” [First Part, Chap. 50]

“It is not the way of the compassionate Maker to create rational beings in order to deliver them over mercilessly to unending affliction in punishment for things of which He knew even before they were fashioned, aware how they would turn out when He created them, and whom nonetheless He created.” [Second Part, Chap. 39]

“This is the mystery: that all creation by means of One, has been brought near to God in a mystery; then it is transmitted to all; thus all is united to Him…This action was performed for all of creation; there will, indeed, be a time when no part will fall short of the whole.” [Third Part, Chap. 5]

Gregory of Nyssa: Our Sister Macrina

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Monasticism, Patristic Pearls, The Cappadocians, Women in Early Christianity on March 7, 2025

Excerpt from Gregory of Nyssa: The Letters, by Ann M. Silvas, Brill, 2007

Gregory of Nyssa – Letter 19 To a certain John

The letter was written from Sebasteia in the first half of AD 380. The brief but intense cameo of Gregory’s sister, 19.6–10, is a foreshadowing and a promise of the Life of Macrina. It is the earliest documentation we have of Macrina’s existence, her way of life and her funeral led by Gregory, written less than a year after her death. The witness of her lifestyle, her conversations with him which were so formative and strengthening of his religious spirit, and above all his providential participation in her dying hours had a profound affect on him. It only needed time to absorb and reflect on these events. Then, when the occasion offered, he set out to make his remarkable sister better known to the world.

Our Sister Macrina

We had a sister who was for us a teacher of how to live, a mother in place of our mother. Such was her freedom towards God that she was for us a strong tower (Ps 60.4) and a shield of favour (Ps 5.13) as the Scripture says, and a fortified city (Ps 30.22, 59.11) and a name of utter assurance, through her freedom towards God that came of her way of life.

She dwelt in a remote part of Pontus, having exiled herself from the life of human beings. Gathered around her was a great choir of virgins whom she had brought forth by her spiritual labour pains (cf. 1 Cor 4.15, Gal 4.19) and guided towards perfection through her consummate care, while she herself imitated the life of angels in a human body.

With her there was no distinction between night and day. Rather, the night showed itself active with the deeds of light (cf. Rom 12.12–13, Eph 5.8) and day imitated the tranquility of night through serenity of life. The psalmodies resounded in her house at all times night and day.

You would have seen a reality incredible even to the eyes: the flesh not seeking its own, the stomach, just as we expect in the Resurrection, having finished with its own impulses, streams of tears poured out (cf. Jer. 9.1, Ps 79.6) to the measure of a cup, the mouth meditating the law at all times (Ps 1.2, 118.70), the ear attentive to divine things, the hand ever active with the commandments (cf. Ps 118.48). How indeed could one bring before the eyes a reality that transcends description in words?

Well then, after I left your region, I had halted among the Cappadocians, when unexpectedly I received some disturbing news of her. There was a ten days’ journey between us, so I covered the whole distance as quickly as possible and at last reached Pontus where I saw her and she saw me.

But it was the same as a traveler at noon whose body is exhausted from the sun. He runs up to a spring, but alas, before he has touched the water, before he has cooled his tongue, all at once the stream dries up before his eyes and he finds the water turned to dust.

So it was with me. At the tenth year I saw her whom I so longed to see, who was for me in place of a mother and a teacher and every good, but before I could satisfy my longing, on the third day I buried her and returned on my way.