Archive for category New Nuggets

The Four Text-Types of NT Textual Criticism

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ancient Christian Manuscripts, First Thoughts, New Nuggets, Theology on March 12, 2026

The four main text-types in New Testament textual criticism are the Alexandrian, Western, Byzantine, and Caesarean. These categories help scholars analyze and compare the thousands of existing manuscripts to reconstruct the original text.

Textual criticism of the New Testament categorizes manuscripts into several text types. The four main text types are:

1. Alexandrian Text-Type

- Date: 2nd–4th centuries CE

- Characteristics: Generally shorter readings, fewer expansions or paraphrases, and more abrupt readings. It is often considered more reliable than other text types. RSV, NRSV, ESV, NASB, NIV, and LEB Bibles are based on Alexandrian-type manuscripts.

2. Western Text-Type

- Date: 2nd–9th centuries CE

- Characteristics: Known for paraphrasing and free alterations. Scribes often changed words and clauses to enhance clarity and meaning.

3. Byzantine Text-Type

- Date: 4th century onward

- Characteristics: Characterized by a larger number of surviving manuscripts. It tends to have more expansions and harmonizations, reflecting a later formalization of the text. The King James and virtually all Reformation era Bibles are based on Byzantine-Type manuscripts.

4. Caesarean Text-Type

- Date: 3rd–4th centuries CE

- Characteristics: A less common type that exhibits features of both the Alexandrian and Western text types. It is primarily associated with the region of Caesarea.

These text types help scholars classify and understand the variations in the New Testament manuscripts and work towards reconstructing the original text.

Major New Testament Text‑Types

| Text‑Type | Key Features | Comments |

| Alexandrian | Earliest, concise, less harmonized; includes Codices Vaticanus & Sinaiticus | Most reliable overall. Basis for RSV, NRSV, ESV, NASB, NIV, and LEB Bibles |

| Western | Paraphrastic, expansions, unique readings (e.g., Codex Bezae) | Valuable but secondary |

| Byzantine | Majority of later manuscripts; smoother, harmonized | Least reliable for earliest text. Basis for King James and Reformation era Bibles |

| Caesarean (disputed) | Regional; mixed features; mostly in Gospels | Interesting but not primary |

David Bentley Hart: “Traditio Deformis – The long history of defective Christian scriptural exegesis occasioned by problematic translations”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ancient Christian Manuscripts, New Nuggets, Theology on March 8, 2026

David Bentley Hart (born 1965) is an American Orthodox Christian philosophical theologian, cultural commentator and polemicist. Here, in one short essay published in “First Things” in May 2015, Prof. Hart addresses, “The long history of defective Christian scriptural exegesis occasioned by problematic translations”.

The long history of defective Christian scriptural exegesis occasioned by problematic translations is a luxuriant one, and its riches are too numerous and exquisitely various adequately to classify. But I think one can arrange most of them along a single continuum in four broad divisions: some misreadings are caused by a translator’s error, others by merely questionable renderings of certain words, others by the unfamiliarity of the original author’s (historically specific) idiom, and still others by the “untranslatable” remoteness of the author’s own (culturally specific) theological concerns. And each kind comes with its own special perils and consequences.

But let me illustrate. Take, for example, Augustine’s magisterial reading of the Letter to the Romans, as unfolded in reams of his writings, and ever thereafter by his theological heirs: perhaps the most sublime “strong misreading” in the history of Christian thought, and one that comprises specimens of all four classes of misprision. Of the first, for instance: the notoriously misleading Latin rendering of Romans 5:12 that deceived Augustine into imagining Paul believed all human beings to have, in some mysterious manner, sinned “in” Adam, which obliged Augustine to think of original sin—bondage to death, mental and moral debility, estrangement from God—ever more insistently in terms of an inherited guilt (a concept as logically coherent as that of a square circle), and which prompted him to assert with such sinewy vigor the justly eternal torment of babes who died unbaptized. And of the second: the way, for instance, Augustine’s misunderstanding of Paul’s theology of election was abetted by the simple contingency of a verb as weak as the Greek proorizein (“sketching out beforehand,” “planning,” etc.) being rendered as praedestinare—etymologically defensible, but connotatively impossible. And of the third: Augustine’s frequent failure to appreciate the degree to which, for Paul, the “works” (erga, opera) he contradistinguishes from faith are works of the Mosaic law, “observances” (circumcision, kosher regulations, and so on). And of the fourth—well, the evidences abound: Augustine’s attempt to reverse the first two terms in the order of election laid out in Romans 8:29–30 (“Whom he foreknew he also marked out beforehand”); or his eagerness, when citing Romans 5:18, to quote the protasis (“Just as one man’s offence led to condemnation for all men”), but his reluctance to quote the (strictly isomorphic) apodosis (“so also one man’s righteousness led to justification unto life for all men”); or, of course, his entire reading of Romans 9–11 . . .

Ah—thereby hangs a tale.

Not that Paul’s argument there is difficult to follow. What preoccupies him is the agonizing mystery that the Messiah has come, yet so few of the house of Israel have accepted him, while so many Gentiles—outside the covenant—have. What then of God’s faithfulness to his promises? It is not an abstract question regarding who is “saved” and who “damned”: By the end of chapter 11, the former category proves to be vastly larger than that of the “elect,” or the “called,” while the latter category makes no appearance at all. It is a concrete question concerning Israel and the Church. And ultimately Paul arrives at an answer drawn, ingeniously, from the logic of election in Hebrew Scripture.

Before reaching that point, however, in a completely and explicitly conditional voice, he limns the problem in the starkest chiaroscuro. We know, he says, that divine election is God’s work alone, not earned but given; it is not by their merit that Gentile believers have been chosen. “Jacob have I loved, but Esau have I hated” (9:13)—here quoting Malachi, for whom Jacob is the type of Israel and Esau the type of Edom. For his own ends, God hardened Pharaoh’s heart. He has mercy on whom he will, hardens whom he will (9:15–18). If you think this unjust, who are you, O man, to reproach God who made you? May not the potter cast his clay for purposes both high and low, as he chooses (9:19–21)? And, so, what if (ei de, quod si) God should show his power by preparing vessels of wrath, solely for destruction, to provide an instructive counterpoint to the riches of the glory he lavishes on vessels prepared for mercy, whom he has called from among the Jews and the Gentiles alike (9:22–24)? Perhaps that is simply how it is: The elect alone are to be saved, and the rest left reprobate, as a display of divine might; God’s faithfulness is his own affair.

Well, so far, so Augustinian. But so also, again, purely conditional: “What if . . . ?” Rather than offering a solution to the quandary that torments him, Paul is simply restating it in its bleakest possible form, at the very brink of despair. But then, instead of stopping here, he continues to question God’s justice after all, and spends the next two chapters unambiguously rejecting this provisional answer altogether, in order to reach a completely different—and far more glorious—conclusion.

Throughout the book of Genesis, the pattern of God’s election is persistently, even perversely antinomian: Ever and again the elder to whom the birthright properly belongs is supplanted by the younger, whom God has chosen in defiance of all natural “justice.” This is practically the running motif uniting the whole text, from Cain and Abel to Manasseh and Ephraim. But—this is crucial—it is a pattern not of exclusion and inclusion, but of a delay and divagation that immensely widens the scope of election, taking in the brother “justly” left out in such a way as to redound to the good of the brother “unjustly” pretermitted. This is clearest in the stories of Jacob and of Joseph, and it is why Esau and Jacob provide so apt a typology for Paul’s argument. For Esau is not finally rejected; the brothers are reconciled, to the increase of both precisely because of their temporary estrangement. And Jacob says to Esau (not the reverse), “Seeing your face is like seeing God’s.”

And so Paul proceeds. In the case of Israel and the Church, election has become even more literally “antinomian”: Christ is the end of the law so that all may attain righteousness, leaving no difference between Jew and Gentile; thus God blesses everyone (10:11–12). As for the believing “remnant” of Israel (11:5), they are elected not as the number of the “saved,” but as the earnest through which all of Israel will be saved (11:26), the part that makes the totality holy (11:16). And, again, the providential ellipticality of election’s course vastly widens its embrace: For now, part of Israel is hardened, but only until the “full entirety” (pleroma) of the Gentiles enter in; they have not been allowed to stumble only to fall, however, and if their failure now enriches the world, how much more so will their own “full entirety” (pleroma); temporarily rejected for “the world’s reconciliation,” they will undergo a restoration that will be a “resurrection from the dead” (11:11–12, 15).

This, then, is the radiant answer dispelling the shadows of Paul’s grim “what if,” the clarion negative: There is no final “illustrative” division between vessels of wrath and of mercy; God has bound everyone in disobedience so as to show mercy to everyone (11:32); all are vessels of wrath so that all may be made vessels of mercy.

Not that one can ever, apparently, be explicit enough. One classic Augustinian construal of Romans 11, particularly in the Reformed tradition, is to claim that Paul’s seemingly extravagant language—“all,” “full entirety,” “the world,” and so on—really still means just that all peoples are saved only in the “exemplary” or “representative” form of the elect. This is, of course, absurd. Paul is clear that it is those not called forth, those allowed to stumble, who will still never be allowed to fall. Such a reading would simply leave Paul in the darkness where he began, reduce his glorious discovery to a dreary tautology, convert his magnificent vision of the vast reach of divine love into a ludicrous cartoon of its squalid narrowness. Yet, on the whole, the Augustinian tradition on these texts has been so broad and mighty that it has, for millions of Christians, effectively evacuated Paul’s argument of all its real content. It ultimately made possible those spasms of theological and moral nihilism that prompted John Calvin to claim (in book 3 of The Institutes) that God predestined even the Fall, and (in his commentary on 1 John) that love belongs not to God’s essence, but only to how the elect experience him. Sic transit gloria Evangelii. I have to say that, as an Orthodox scholar, I have made many efforts over the years to defend Augustine against what I take to be defective and purely polemical Eastern interpretations of his thought, in the realms of metaphysics, Trinitarian theology, and the soul’s knowledge of God (often to the annoyance of some of my fellow Orthodox). But regarding that part of his intellectual patrimony that has had the widest effect—his understanding of sin, grace, and election—not only do I share the Eastern distaste for (or, frankly, horror at) his conclusions; I am even something of an extremist in that respect. In the whole long, rich history of Christian misreadings of Scripture, none I think has ever been more consequential, more invincibly perennial, or more disastrous.

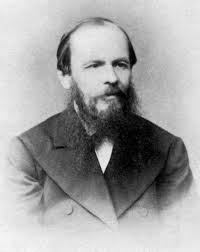

Dostoyevsky: “… all-embracing love.”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, Heaven and Hell, New Nuggets, Theology, Universal Restoration (Apokatastasis) on March 6, 2026

Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821 – 1881) – Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist, journalist, and philosopher.

“Love [people] even in [their] sin, for that is the semblance of Divine Love and is the highest love on earth. Love all God’s creation, the whole and every grain of sand in it. Love every leaf, every ray of God’s light. Love the animals, love the plants, love everything. If you love everything, you will perceive the divine mystery in things. Once you have perceived it, you will begin to comprehend it better every day. And you will come at last to love the whole world with an all-embracing love.”

—Fyodor Dostoyevsky, from The Brothers Karamazov

Fr. Richard Rohr, OFM: “Jesus the Prophet”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, New Nuggets, Theology on October 15, 2025

In a homily Father Richard Rohr, OFM, describes the tension between priestly and prophetic tasks—both necessary for healthy religion:

There are two great strains of spiritual teachers in Judaism, and I think, if the truth is told, in all religions. There’s the priestly strain that holds the system together by repeating the tradition. The one we’re less familiar with is the prophetic strain, because that one hasn’t been quite as accepted. Prophets are critical of the very system that the priests maintain.

If we have both, we have a certain kind of wholeness or integrity. If we just have priests, we keep repeating the party line and everything is about loyalty, conformity, and following the rules—and that looks like religion. But if we have the priest and the prophet, we have a system constantly refining itself and correcting itself from within. Those two strains very seldom come together. We see it in Moses, who both gathers Israel, and yet is the most critical of his own people. We see it again in Jesus, who loves his people and his Jewish religion, but is lethally critical of hypocrisy and illusion and deceit (see Matthew 23; Luke 11:37–12:3).

Choctaw elder and Episcopal bishop Steven Charleston considers how Jesus invited others to share in his prophetic vision:

Jesus … saw a vision that became an invitation for people to claim a new identity, to enter into a new sense of community.… Jesus offered the promise of justice, healing, and redemption.… Jesus became the prophetic teacher of a spiritual renewal for the poor and the oppressed…. Jesus was more than just the recipient of a vision or the messenger of a vision. What sets Jesus apart is that he brought the elements of his vision quest together in a way that no one else had ever done….

“This is my body,” he told them. “This is my blood.” For him, the culmination of his vision was not just the messiahship of believing in him as a prophet. Through the Eucharist, Jesus was not just offering people a chance to see his vision, but to become a part of it by becoming a part of him.

Richard honors the role of prophets in religious systems:

The only way evil can succeed is to disguise itself as good. And one of the best disguises for evil is religion. Someone can be racist, be against the poor, hate immigrants, and be totally concerned about making money and being a materialist but still go to church each Sunday and be “justified” in the eyes of religion.

Those are the things that prophets point out, so prophets aren’t nearly as popular as priests. Priests keep repeating the party line, but prophets do both: they put together the best of the conservative with the best of the liberal, to use contemporary language. They honor the tradition, and they also say what’s phony about the tradition. That’s what fully spiritually mature people can do.

Richard Rohr’s Daily Meditation – Monday, October 13, 2025

When Glory Explodes the Forms: Doxology, Faith, and the Exorcism of Epistemology

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, New Nuggets, Theology on July 14, 2025

by John Stamps* Δόξα Πατρὶ καὶ Υἱῷ καὶ Ἁγίῳ Πνεύματι . . . I was paying attention in church last Sunday—really, I was. But when Fr. Nebojša intoned: “Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit, both now and always and unto the ages of ages,” a strange Platonic thought hijacked my brain. Socrates wouldn’t understand a word of this. For him, doxa meant “opinion.” The Father has an opinion? The Son too? And the Holy Spirit? Three divine “opinions”? Socrates would be horrified. In Book VI of The Republic, he blurts out: “Have you not observed that opinions (doxai) divorced from knowledge (episteme) are ugly things? The best of them are blind.” (506c) Already, he’d be reaching for the hemlock. But it gets worse. At St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church, when we recite the Nicene Creed—first in Greek, then in English—we fervently confess: Πιστεύω εἰς ἕνα Θεὸν Πατέρα παντοκράτορα . . . “I believe in one God, the Father Almighty.” Or, more provocatively—and more Christianly—“I put my trust in one God, the Father Almighty.” Once again, Socrates would be scandalized. Pistis? Mere belief? Conviction at best? And you’re going to stake that on ultimate reality? Pistis may rise above illusion (eikasia), but it’s still fog—not the clear light of truth. Surely the divine deserves better. Surely epistēmē—solid, demonstrable knowledge—is the true coin of the metaphysical realm. To entrust pistis with the highest things would be like trying to buy eternity with Monopoly money. For Plato, pistis belongs low on the Divided Line—just above eikasia (imagination and shadows), and well below epistēmē. It’s trust in what we can see and touch, but without glimpsing the hidden reality behind it—the invisible Forms that give things their true meaning. Pistis is for the unphilosophical. The half-blind. The cave-dwellers huddled in the cave who mistake sensible things for what is really real. But Christian theology flips the entire Platonic ladder upside down. From Doxa to Glory For Socrates, doxa means “opinion”—an unreliable, subjective mental state. But in Christian liturgy, doxa is glory: not mental conjecture but the radiant, overwhelming presence of the living God. Doxa is Moses taking off his shoes before the burning bush. Doxa is Moses descending Sinai with a face that glows because he got too close to raw holiness. Doxa is the Word made flesh, full of grace and truth, dwelling among us. Doxa is not conjecture. It’s encounter. Somewhere between the Hebrew Bible and the Septuagint, doxa got an upgrade. And this raises a linguistic and theological mystery: How did the Hebrew word כָּבוֹד (kavod—weight, substance, heaviness, splendor) become doxa (opinion) in Greek? The Septuagint translators had choices. And their choice changed Christian theology forever. From Pistis to Trust In the New Testament, pistis is not an epistemic crutch. It is relational trust, covenant loyalty, and a faithful response to a God who reveals Himself not in abstractions but in history, flesh, and self-giving love. Far from being a lower form of knowledge, pistis becomes the primary way humans recognize and respond to divine glory—a deeper, riskier kind of knowing, grounded in love, testimony, and encounter. For Socrates, by contrast, pistis was barely a step above guesswork—an uncritical belief in the physical world, just above imagination (eikasia) and far below true knowledge (epistēmē). It belonged to the realm of opinion (doxa) and was reserved for the half-blind dwellers in the cave. But in the New Testament, pistis becomes something far more daring. It echoes the Hebrew word emunah (אֱמוּנָה): steadfast trust, covenant faithfulness, unwavering reliability. Christian faith isn’t vague optimism. It’s not mere intellectual assent or rearranging our mental furniture. Pistis is not a foggy feeling or private conviction. It is existential trust. It is covenantal loyalty. It is Semper Fi!— our fidelity to the God who speaks, acts, and keeps His promises and our willingness to stake everything on His trustworthiness. Faith is stepping out onto the water like Peter because Jesus said, “Come.” Faith is betting everything on the God who delivered Israel from Pharaoh’s tyranny and raised Jesus from the dead. Or, as Robert Jenson once put it: “God is whoever raised Jesus from the dead, having before raised Israel from Egypt.” This is how Christians reliably identify and name God: by His acts of faithfulness. And pistis is our answering act of trust and faithfulness in return. From Eikasia to Icon Images are tricky. Plato had his reasons to be suspicious. He especially distrusted imitative images—whether in poetry, painting, or shadowplay—because they were seductive lies, copies of copies, that lured the soul away from truth and down into the flickering cave of illusion. Teenagers glued to their 300-DPI iPhone screens aren’t so different from the cave-dwellers in The Republic, staring at shadows on the wall, mistaking illusion for reality. That’s why Plato wanted the image-makers banished from the ideal city. For him, images were not innocent—they were propaganda, simulacra, distortions. In his metaphysics, images were the lowest of the low. But Christian theology tells a different story. Scripture gives us strong reasons to trust—not all images, but certain ones—as truth-bearing windows into reality. First, just look at yourself in the mirror—warts and all. You are the imago Dei. Look at your spouse, your children, your friends. Knock on your neighbor’s door with cookies or a bottle of wine. Hand $20 to a homeless person. Pray for—and forgive—your bitterest enemy. Why this exercise? Because every one of them is the imago Dei. They are the spitting image of God. This is where Christian theology begins: with the startling claim that human beings are made in the image and likeness of God. We bear the weight of glory. This image (εἰκών) is not falsehood. It is truth-bearing. It carries the imprint of the Creator. The image is not a pale copy—it participates in the reality it reflects. This image is a site where divine glory dwells. Second, when the Word became flesh, God’s image wasn’t entering alien territory. The Incarnation is not some bizarre intrusion into a world God otherwise keeps at arm’s length. It is the culmination of God’s long purpose for creation: that divine glory would dwell bodily within it. The Incarnation is no invasion. The kosmos belongs to the Lord, and the fullness thereof. Third, Jesus of Nazareth is the Image-Bearer par excellence. He looks just like us. That God was one of us is the scandal at the heart of the Christian confession. And yet . . . the One in whom all the fullness of God dwells (Colossians 2:9) looks so much like us that we don’t recognize Him. Familiarity breeds contempt and generates its own kind of blindness. Glory walks right past us wearing dusty sandals. But if we have eyes to behold the mystery, Jesus—crucified, risen, and ascended—is the true Image (εἰκών) of the invisible God (Colossians 1:15). Not a photocopy. Not a metaphor. Not a shadow. He is one of us—bone of our bone, flesh of our flesh. And yet He reveals God to us fully and truly. We Orthodox insist on this incarnational truth: images matter because the Image matters. To celebrate this, we wallpaper our churches with icons—not as decoration, but as theological proclamation. Icons are not aesthetic accessories. They are visual participation in divine reality. Icons reveal. They manifest. They make present. They proclaim what words alone cannot say. Why do we venerate icons? Because images, rightly ordered, are truth-bearing. Because the Image became flesh and dwelt among us. And because, through Christ, we too are being transfigured—from glory to glory—into the image of God. For us, seeing is not believing lies. Seeing is encountering glory. Epistemology Needs an Exorcism My old philosophy professor, Nicholas Wolterstorff, used to warn us: “Ever since Plato, the Western world has been haunted by the lure of certitude.” And he’s right. That ghost still lingers. We need an exorcism. We need to turn epistemology into doxology. Or more precisely: episteme-logos into doxo-logos. Once you’re bewitched by epistemology and the certainty it promises, it’s hard to break the spell. You start—and you end—by measuring all truth, including theological truth, by mental clarity, logical deduction, and timeless abstraction. But Trinitarian doxology and the Nicene Creed don’t just challenge Greek epistemology—they scandalize it. We can’t start with clear and distinct ideas. We must begin with faithful witness. We begin where we actually encounter the glory of God. The Father who speaks. The Son who acts. The Spirit who breathes. Three Persons. One God. Doxology—not detached speculation—is the engine that drives Christian theology. To the Greek philosophical mind—fixated on unchanging forms, impersonal absolutes, and epistemic certainty—this kind of God-talk sounds like theological madness. A God who speaks? Acts? Loves? Suffers? Raises the dead? So yes—we fumble and stumble for the right words. Apophatic theology rightly reminds us that God always exceeds our categories and language. But that doesn’t mean we stay silent. Christian speech begins in worship—yes, in doxology—and in the risky act of saying something true about the God who cannot be contained. Let the Platonists chase certainty . . . we behold glory. For the life of me, I still don’t fully understand how kavod—a word of weight and substance—became doxa, a word that once meant “opinion.” But the Septuagint translators had choices. And their choice opened the door for Christian theology to do something the ancient philosophers never saw coming. Faithful God-talk begins not with control, but with wonder. Not with clarity, but with trust. Not with epistemic mastery, but with doxology. We speak because God has spoken. We bear witness because doxa showed up in history, and refused to stay abstract. We dare to name the Unnameable because the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth . . . and we beheld His glory. Let the Platonists chase their Forms, the Cartesians polish their clear and distinct ideas, and the positivists flatten everything into data. And yes, let the American Fundamentalists obsess over the inerrancy of the original autographs—those long-lost parchments that somehow guarantee perfect doctrine, if only we squint hard enough. Scripture, for them, isn’t the living voice that calls us into communion, but a cosmic answer key dropped from heaven. The lure of certitude is still a mirage. We will not lose our nerve. We will render doxa to the God who acts— Who speaks, Who raises the dead, Who walks through our kosmos with dusty feet and scandalous grace. . . . καὶ νῦν καὶ ἀεὶ καὶ εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων. Ἀμήν.  * * *John Stamps is Senior Technical Writer at Guidewire Software in San Mateo, California. He holds a BA in Greek from Abilene Christian University, an MDiv from Princeton Theological Seminary, and pursued further study in the philosophy of religion at Yale Divinity School—just long enough to accrue debt and existential questions. He attends St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church in San Jose, is married to the long-suffering Shelly Houston Stamps, plays mediocre tennis with misplaced confidence, and speaks Spanish that routinely scandalizes native speakers and small children. |

The Seven Sacraments, or Mysteries of the Christian Church

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, New Nuggets, Theology on April 2, 2025

The inward life of the Christian Church is mystical (or sacramental). The word “mysteries” (Greek mysteria) is the term used in the Orthodox East; “sacraments” (Latin sacramenta), the term used in the Latin West. So, how and when did Western Latin and Eastern Orthodox come to identify and accept the seven sacraments, or mysteries of the Christian Church?

One might reasonably assume that the seven Sacraments (Mysteries) were determined early in the period of the united Church (AD 33 – 1054). That assumption would be false.

One of the renowned teachers of the united Church, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (6th Century) listed six sacraments in his work The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy (ca. AD 500): baptism, Eucharist, confirmation, priesthood, the consecration of monks, and rites for the dead.

Two centuries later, another early teacher revered East and West, John of Damascus (675-749), mentions only two sacraments: Baptism together with the corresponding chrismation and the Eucharist (Communion), the only two mysteries identified in the New Testament and instituted by Jesus.

Clearly, there was no unanimity on the identity or number of sacraments/mysteries in the first 1,000 years of the unified Christian Church, nor at the time of the Great East-West Schism of 1054.

In the post-Schism Latin West, Peter Lombard (1100-1164), in his fourth Book of Sentences (d.ii, n.1), enumerated the seven sacraments. This list of sacraments was accepted by the Western Latin Roman Church at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215.

49 years later, during the Second Ecumenical Council of Lyons in 1274, Eastern Greek theologians, under Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos (in his Profession of Faith), accepted the seven Latin Sacraments: Baptism, Confirmation (Chrismation), Eucharist, Penance, Priesthood, Marriage, and Anointing of the Sick.

So, clearly, neither the Seven Holy Sacraments of the Roman Catholic Church nor the Seven Holy Mysteries of the Eastern Orthodox Church are First Thoughts of God, but mostly, save two, distant Afterthoughts of Man, codified a thousand years after Jesus and the Apostolic age.

New Testament “Love”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in New Nuggets, Theology on March 31, 2025

Koine (common) Greek, the Greek of the New Testament, is often much more specific than English. This is important for those wanting to understand exactly what the New Testament means. An example of this specificity is the Koine Greek words used to describe the word “love.”

In English, the word “love” can be applied to a variety of types of love. “Love” can apply to feelings toward a spouse, parents, siblings, strangers, or even a cup of coffee. Koine Greek, however, uses a specific word for each type of love. Here are the Greek words that were used during Christ’s time to convey the different meanings of the word “Love”:

- Eros (ἔρως): Refers to romantic love felt towards one’s spouse or lover. This Greek term is where the word “erotic” is derived from. The word “Eros” is not actually used in either the Old or New Testaments.

- Phileo (φιλέω): Refers to feelings one has towards close friends; “brotherly love”. This word was used in the New Testament to describe Jesus’ love for his disciples (John 20:2) and for Lazarus (John 11:3).

- Agape (ἀγάπη): Sometimes called “God’s kind of love”. This is the kind of love that we should have for all men, and also for our enemies. It is a selfless kind of love that Christians must have in regard to acting in the best interest for all human beings. “But I say unto you, love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you;” (Matthew 5:44).

- Storge (στοργή): This Greek word refers to love we have for our parents, siblings, our children and other members of our family. Paul used this word in the negative in Romans 1:31 when he described the pagans that he was in contact with as being without “natural affection.”

Human Institutions

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, New Nuggets on March 31, 2025

Nothing on earth has a stronger amoral drive for survival than a human institution.

Prayer Ropes and Rosaries

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, Monasticism, New Nuggets, Patristic Pearls on December 21, 2024

Both the prayer rope and the rosary are revered traditional aids to Christian prayer, yet each has its own unique origin, symbolism, and devotional use.

The Prayer Rope, now largely associated with the Eastern Orthodox Church, is a loop of knots (each knot containing seven crosses), usually made of wool, that is used to focus and intensify prayer, particularly the Jesus Prayer. It acts as a physical guide for a repeated, meditative style of prayer, allowing practitioners to keep count while reflecting and meditating. The prayer rope has its beginnings in early fourth century Christian monasticism in the Egyptian Desert, where it was devised as a tool to aid in the ascetic practice of continuous prayer (1 Thes. 5:17).

Origins: The prayer rope is known as a ‘komboskini’ in Greek and ‘chotki’ in Russian. The prayer rope owes its origins to St. Pachomius the Great, a fourth century “Desert Father” in upper Egypt and founder of cenobitic monasticism (a monastic tradition that stresses community life, over the older, eremitic, or solitary tradition). St. Pachomius established the prayer rope as a practical solution for the monks under his supervision to count prayers and prostrations consistently. The prayer rope evolved as a useful instrument for monks to keep track of their prayers, particularly the Jesus Prayer, without distraction. It gradually took on a deeper spiritual value, with each knot symbolizing a request for mercy and humility.

Symbolic Significance: Wool knots, each knot containing seven crosses, are commonly used on traditional prayer ropes to represent Christ’s flock and the shepherd’s care. The number of knots in a prayer rope varies; typically 33 (Christ’s age at crucifixion), 50, or 100.

Traditional Use: In Orthodox Christian practice, the prayer rope is typically used for private prayer in reciting the Jesus Prayer, acting as a physical and spiritual guide to help the mind (nous) and heart concentrate on prayer.

The Rosary, strongly associated with the Roman Catholic Church, is a string of beads that ends with a crucifix and is used to guide Catholics through a sequence of prayers that reflect on the lives of Christ and the Virgin Mary. Each bead signifies a specific prayer, such as the Hail Mary, and each set of beads makes a ‘decade’ that corresponds to a mystery in Christ’s life. The rosary has a long history, dating back to the Middle Ages when it first arose as a popular form of laity devotion, eventually becoming a prominent practice in Catholic piety.

Origins: The rosary is typically identified with Saint Dominic in the early 13th century. The rosary began as a simple way for lay people to join in the monastic practice of reciting the Psalms, but has since evolved into a systematic form of prayer. The rosary prayers are split into decades, each with ten Hail Marys, an Our Father, and a Glory Be, and are frequently accompanied by meditations on the Mysteries of the Rosary.

Symbolic Significance: Each rosary bead represents a prayer as well as a step in the meditation journey through Jesus Christ’s and the Virgin Mary’s lives. The rosary culminates with a crucifix, which represents Christ’s sacrifice.

Traditional Use: Roman Catholics utilize the rosary for both personal meditation and social worship. It is frequently prayed privately for personal spiritual development or in groups for social objectives and celebrations.