Archive for category Hesychasm – Jesus Prayer

The Orthodox Prayer Rope

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, New Nuggets on October 20, 2017

The prayer rope (Greek: κομποσκοίνι, “komboskini”; Russian: чётки, “chotki”) is part of the habit of Eastern Orthodox monks and nuns and is employed by monastics and by others, clergy and laity alike, to count the number of times one has prayed the Jesus Prayer or, occasionally, other prayers. The prayer rope is traditionally made out of wool, symbolizing the flock of Christ. The traditional color of the rope is black (symbolizing mourning for one’s sins), with either black or colored beads. The beads (if they are colored) are traditionally red, symbolizing the blood of Christ and the blood of the martyrs. Prayer ropes are tied in a loop, terminating in a cross. The original prayer rope had 33 knots to symbolize the age of Jesus Christ when he died. Prayer ropes may come in different lengths in addition to the 33 knot standard to include 50 knot, 100 knot, and even 300 knot lengths.

Though prayer ropes are often tied by monastics, lay persons are permitted to tie them also. In proper practice, the person tying a prayer rope should be of true faith and pious life and should be praying the Jesus Prayer the whole time.

Origins

The invention of the prayer rope is attributed to Saint Pachomius in the fourth century as an aid for illiterate monks to accomplish a consistent number of prayers and prostrations in their cells. Previously, monks would count their prayers by casting pebbles into a bowl, but this was cumbersome, and could not be easily carried about when outside the cell. The use of the rope made it possible to pray the Jesus Prayer unceasingly, whether inside the cell or out, in accordance with Saint Paul’s injunction to “Pray without ceasing” (I Thessalonians 5:17).

The Seven-Cross Knot

It is said that the method of tying the prayer rope had its origins from the Father of Orthodox Monasticism, Saint Anthony the Great. He started by tying a leather rope with a simple knot for every time he prayed Kyrie Eleison (“Lord have Mercy”), but the Devil would come and untie the knots to throw off his count. He then devised a way—inspired by a vision he had of the Theotokos—of tying the knots so that the knots themselves would constantly make the sign of the cross. This is why prayer ropes today are still tied using knots that each contain seven little crosses being tied over and over. The Devil could not untie it because the Devil is vanquished by the Sign of the Cross.

Using the Prayer Rope

When praying, the user normally holds the prayer rope in the left hand, leaving the right hand free to make the Sign of the Cross. When not in use, the prayer rope is traditionally wrapped around the left wrist so that it continues to remind one to pray without ceasing. If this is impractical, it may be placed in the (left) pocket, but should not be hung around the neck or suspended from the belt. The reason for this is humility: one should not be ostentatious or conspicuous in displaying the prayer rope for others to see.

Evagrius Ponticus: “The Eight Evil Thoughts (Logísmoi)”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, Monasticism on October 20, 2017

Evagrius Ponticus (c.346-399) – was originally from Pontus, on the southern coast of the Black Sea in what is modern-day Turkey. He served as a Lector under St. Basil the Great and was made Deacon and Archdeacon under St. Gregory of Nazianzus. In order to deal with his personal sin, Evagrius retreated to the Egyptian desert and joined a cenobitic community of Desert Fathers. As a classically trained scholar, Evagrius recorded the sayings of the desert monks and developed his own theological writings.

In AD 375, Evagrius developed a comprehensive list of eight evil “thoughts” (λογισμοι; logísmoi), or eight terrible temptations, from which all sinful behavior springs. This list was intended to serve a diagnostic purpose: to help his readers (fellow desert monks) identify the process of temptation, their own strengths and weaknesses, and the remedies available for overcoming temptation.

The “thoughts” (logísmoi) that concern Evagrius (cf., Skemmata 40–62) are the so-called “eight evil thoughts”. The basic list appears again and again in his writings:

1. Gluttony – (γαστριμαργία; gastrimargía);

2. Lust or Fornication – (πορνεία; porneía);

3. Avarice or Love of money – (φιλαργυρία; philarguría);

4. Dejection or Sadness – (λύπη; lúpe);

5. Anger – (ὀργή; orgé);

6. Despondency or Listlessness – (ἀκηδία; akedía);

7. Vainglory – (κενοδοξία; kenodoxía);

8. Pride – (ὑπερηφανία; huperephanía).

The order in which Evagrius lists the “thoughts” is deliberate. Firstly, it reflects the general development of spiritual life: beginners contend against the grosser and more materialistic thoughts (gluttony, lust, avarice); those in the middle of the journey are confronted by the more inward temptations (dejection, anger, despondency); the more advanced, already initiated into contemplation, still need to guard themselves against the most subtle and “spiritual” of the thoughts (vainglory and pride). Secondly, the list of eight thoughts reflects the threefold division of the human person into the appetitive (επιθυμητικόν; epithymitikón), the incensive (θυμικόν; thymikón), and the intelligent (λογιστικόν; logistikón) aspects. The first part of the soul is the epithymikón, the “appetitive” aspect of the soul. This is the part of the soul that desires things, such as food, water, shelter, sexual relations, relationships with people, and so on. The second part of the soul is the thymikón, which is usually translated the “incensive” aspect. This translation is a bit misleading. The thymikón is indeed the part of the soul that gets angry, but it also has to do with strong feelings of any kind. The third part of the soul, the logistikón, is the “intelligent” or “rational” aspect of the soul. The part of the logistikón that thinks and reasons is called the diánoia (διάνοια), but it is not as important to Evagrius and the other Greek Fathers as the nous (νου̃ς), the “mind”, or to be very precise, the part of the mind that knows when something is true just upon perceiving it.

Gluttony, lust, and avarice are more especially linked with the appetitive aspect; dejection, anger, and despondency, with the incensive power; vainglory and pride, with the intelligent aspect.

Evagrius’ disciple, St. John Cassian, transmitted this list of the eight “thoughts” to the West with some modification. Further changes were made by St. Gregory the Great, Pope of Rome (AD 590 – 604) and these came down to the West through the Middle Ages as the “Seven Deadly Sins” of vainglory, envy, anger, dejection, avarice, gluttony, and lust.

Fr. Zacharias: “The Heart of Man”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, New Nuggets on October 10, 2017

Archimandrite Zacharias (Zacharou) , Ph. D., is a disciple of Elder Sophrony, who was a disciple of St. Silouan of Mount Athos. Presently, Fr. Zacharias is a monk in the Monastery founded by Elder Sophrony: The Monastery of St. John the Baptist, Tolleshunt Knights by Maldon, Essex, England.

“The heart is within our chest. When we speak of the heart, we speak of our spiritual heart which coincides with the fleshly one; but when man receives illumination and sanctification, then his whole being becomes a heart. The heart is synonymous with the soul, with the spirit; it is a spiritual place where man finds his unity, where his nous is enthroned when it has been healed of the passions. Not only his nous, but his whole body too is concentrated there. St. Gregory Palamas says that the heart is the very body of our body, a place where man’s whole being becomes like a knot. When mind [rational faculty] and heart [noetic faculty] unite, man possesses his [whole] nature and there is no dispersion and division in him any more. That is the sanctified state of the man who is healed.

“The heart is within our chest. When we speak of the heart, we speak of our spiritual heart which coincides with the fleshly one; but when man receives illumination and sanctification, then his whole being becomes a heart. The heart is synonymous with the soul, with the spirit; it is a spiritual place where man finds his unity, where his nous is enthroned when it has been healed of the passions. Not only his nous, but his whole body too is concentrated there. St. Gregory Palamas says that the heart is the very body of our body, a place where man’s whole being becomes like a knot. When mind [rational faculty] and heart [noetic faculty] unite, man possesses his [whole] nature and there is no dispersion and division in him any more. That is the sanctified state of the man who is healed.

On the contrary, in our natural and fallen state, we are divided: we think one thing with our mind, we feel another with our senses, we desire yet another with our heart. However, when mind and heart are united by the grace of God, then man has only one thought — the thought of God; he has only one desire — the desire for God; and only one sensation — the noetic sensation of God.” ~ Very Rev. Archimandrite Zacharias (Zacharou)

Chumley: “Silence (hesychia): A Method for Experiencing God “

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, New Nuggets on January 22, 2017

Dr. Norris J. Chumley is on the faculty of New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, in the Kanbar Institute for Undergraduate Film and Television. He is also the author of several books including, “Be Still and Know: God’s Presence in Silence” and “Mysteries of the Jesus Prayer”, a companion book to the feature film and public television special.

“The practice of silence of the Greek, hesychia, the withdrawal from the external world with focus on inward stillness, contemplation, and prayer, and hesychasm, the later Athonite movement of prayer and bodily positioning in Orthodox monasticism, is a method of experiencing God predicated on the belief that a direct spiritual experience and union with God is possible. Long lines of hesychasts, from the second century to the present day, spoke and wrote about the fruits of their experiences.” ~ From the book Be Still and Know: God’s Presence in Silence. 2014

“The practice of silence of the Greek, hesychia, the withdrawal from the external world with focus on inward stillness, contemplation, and prayer, and hesychasm, the later Athonite movement of prayer and bodily positioning in Orthodox monasticism, is a method of experiencing God predicated on the belief that a direct spiritual experience and union with God is possible. Long lines of hesychasts, from the second century to the present day, spoke and wrote about the fruits of their experiences.” ~ From the book Be Still and Know: God’s Presence in Silence. 2014

Unknown Athonite Monk: “Concerning noetic prayer, prayer of the heart, and watchful prayer.”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, Patristic Pearls on January 16, 2017

The following excerpt is from an anonymous 1851 manuscript called The Watchful Mind. It was penned by an unknown monk on Mount Athos, the “Holy Mountain”, the continuous home of the “hesychastic” contemplative Christian prayer tradition for more than a thousand years.

“Beloved, when you wish to pray noetically from your depths, let the prayer of your heart imitate the sound of the cicada. When the cicada chirps, it does so in two ways. At first, it softly chirps five to ten times, but then its ending chirps are more pronounced, drawn out, and melodic. And so, beloved when you pray noetically within your heart, pray in the following manner: First say, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me” about ten times, forcefully from your heart and clearly with your intellect from your depths, one time with each breath. Restrain your breath a little each time you say the prayer as your heart meditates from its depth on the words. Once you have said the prayer in this fashion ten times or more until that place within you has become warm where you meditate upon the prayer, then say the prayer more forcefully, with greater tension and forcefulness of heart, just as the cicada ends its song with a more pronounced and melodic voice.

“Beloved, when you wish to pray noetically from your depths, let the prayer of your heart imitate the sound of the cicada. When the cicada chirps, it does so in two ways. At first, it softly chirps five to ten times, but then its ending chirps are more pronounced, drawn out, and melodic. And so, beloved when you pray noetically within your heart, pray in the following manner: First say, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me” about ten times, forcefully from your heart and clearly with your intellect from your depths, one time with each breath. Restrain your breath a little each time you say the prayer as your heart meditates from its depth on the words. Once you have said the prayer in this fashion ten times or more until that place within you has become warm where you meditate upon the prayer, then say the prayer more forcefully, with greater tension and forcefulness of heart, just as the cicada ends its song with a more pronounced and melodic voice.

This prayer, which is referred to principally as noetic prayer, is also called prayer of the heart and watchful prayer. When you say the prayer with your intellect and repeat it mystically within you in stillness, using your inner voice, it is referred to as noetic prayer. When you say the prayer from the depths of your heart with great tension and inner force, then it is referred to as prayer of the heart. It is referred to as watchful prayer when, because of your prayer or because of the infinite goodness of God, the grace of the Holy Spirit visits your soul and touches your heart, or you are granted a divine vision, upon which your mind’s eye becomes watchful and fixed.

When you practice noetic prayer and reverently repeat it as you should, and the grace of the Holy Spirit visits your soul, then the name of Christ that you are meditating upon with your intellect becomes greatly consoling and sweet to your mind and soul, so much that you could never repeat it enough.

When you practice prayer of the heart and the grace of God touches your heart (that is, when your heart happens upon it), causing it to conceive compunction, as the Lady Theotokos [“God Bearer”, the Virgin Mary] conceived the Word of God by the Holy Spirit, then the name of divine Jesus, and all of Holy Scripture, becomes ineffable sweetness to the heart, and every spiritual notion of the heart (if I may put it this way) becomes a sweet flowing river of divine compunction that sweetens the heart and wondrously makes it fervent in eros and love for it Creator and God.

Sometimes, when you practice prayer of the heart with pain of an enfeebled heart and with sorrow of a humbled soul, then your soul clearly feels the consolation and visitation of the Lord. This is what the prophet says: “The Lord is near those who are brokenhearted.” The Lord invisibly draws near you when you crush your heart with the prayer, as we said, in order to show you some mystical revelation. He shows you some vision in order to make you more fervent in the spiritual work of your heart.

And so, beloved, when, by the grace of Christ, your soul beholds some vision and is filled with compunction because of your prayer, then you understand that watchful prayer is nothing other than divine grace; it is the noetic and divine vision your mind beholds, your intellect firmly fixed upon, and your soul watches. And that the divine grace of the Holy Spirit visited your soul, gently touched your heart, and ineffably sweetened your mind, only you can understand and comprehend within yourself, because compunction ceaselessly from your heart as from an ever-flowing spring, while your mind experiences an inexpressible sweetness and your soul consolation. At that moment your soul possesses some spiritual boldness and mystically supplicates God, its Fashioner and Creator saying, “Remember me, Oh Lord, in your Kingdom,” or some other verse of Holy Scripture.

This holy and pure supplication that takes place within the soul has such power that it penetrates the heavens and reaches the throne of the Holy Trinity, before whom it stands like sweet-smelling and fragrant incense. The prophet said about this prayer, “Let my prayer arise as incense before you.” The God in Trinity receives this holy supplication in an inexpressible and wondrous manner, and the supplication in turn receives the fruit of the Holy Spirit. This fruit, received reverently and modestly, is offered and sent to the soul as a priceless and heavenly gift from the God of all as a pledge of the future kingdom and adoption. The soul that receives the heavenly and divine fruit of the Holy Spirit because of its supplication, that is, from pure prayer, acquires divine love, spiritual joy, peace of heart, and great patience during the hardships and temptations of this age, excellence and goodness in everything, unwavering faith, Christ’s meekness, and passion-killing self-control. All of these are called “fruit of the Holy Spirit.” To our God be glory and power unto ages of ages. Amen.” ~ The Watchful Mind, pp 123-125.

Andrew Louth: “Eastern Christian ‘Mystical Life’. Is it ‘Theoretical’?”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, New Nuggets on December 11, 2016

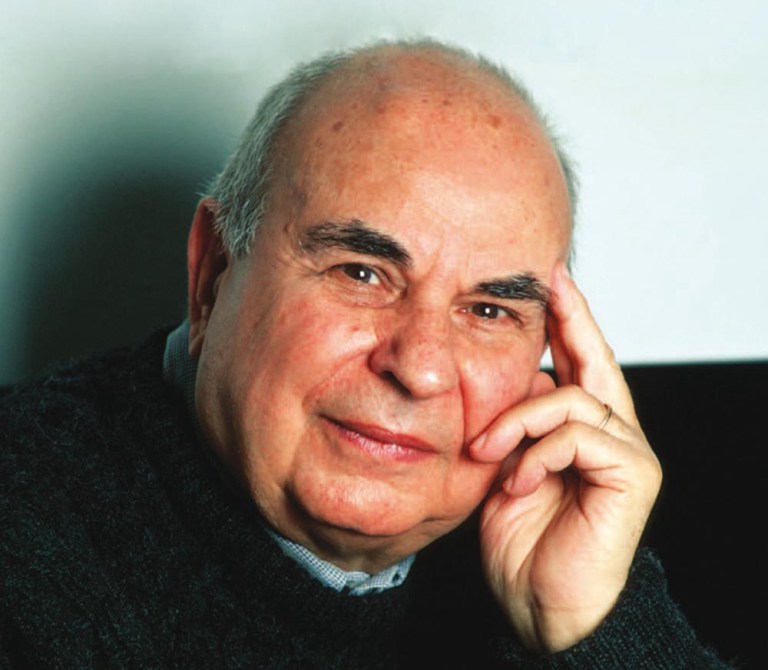

Andrew Louth (1944 – ) – is a Christian theologian, Eastern Orthodox priest, and Professor of Patristic and Byzantine Studies at the University of Durham, England. He has taught at Durham since 1996, and previously taught at Oxford and the University of London. Louth is an expert in the history and theology of Eastern Christianity.

“In particular, what we find in the [Eastern] Fathers undermines any tendency towards seeing mysticism as an elite, individualist quest for ‘peak’ experiences; rather for them the ‘mystical life’ is the ‘life with Christ hid in God’ of Colossians 3:3, a life which is eccle sial, that is lived in the Body of Christ, which is nourished liturgically, and which is certainly a matter of experience, though not of extraordinary ‘experiences’. One could perhaps make this point by finally reflecting briefly on the transformation of one of the words used by the Fathers in connection with the ‘mystical life’: the word theoretikos. The modern word ‘theoretical’ (and indeed the word theoretikos in Modern Greek) means abstract, hypothetical, speculative – the very opposite of practical and experiential. The modern mystical quest is precisely not theoretical. Much modern Christian apologetic exploits this split between the theoretical and the experiential and presents Christianity as a matter of lived experience, not abstract theoretical matters, among which the dogmatic is often included. In the Greek of the Fathers, however, this split can scarcely be represented in words or concepts. Theoretikos means contemplative; that is, seeing and knowing in a deep and transforming way. The ‘practical’, praktikos …, is the personal struggle with our too often wayward drives and desires, which prepares for the exercise of contemplation, theoria; that is, a dispassionate seeing and awareness constituting genuine knowledge, a knowledge that is more than information, however accurate – a real participation in that which is known, in the One whom we come to know. The word theoretikos came to be one of the most common words in Byzantine Greek for designating the deeper meaning of the Scriptures, where one found oneself caught up in the contemplation, theoria, of Christ. The mystical life, the ‘theoretical’ life, is what we experience when we are caught up in the contemplation of Christ, when, in that contemplation, we come to know ‘face to face’ and, as the Apostle Paul puts it, ‘know, even as I am known’ (1 Cor. 13:12).”

sial, that is lived in the Body of Christ, which is nourished liturgically, and which is certainly a matter of experience, though not of extraordinary ‘experiences’. One could perhaps make this point by finally reflecting briefly on the transformation of one of the words used by the Fathers in connection with the ‘mystical life’: the word theoretikos. The modern word ‘theoretical’ (and indeed the word theoretikos in Modern Greek) means abstract, hypothetical, speculative – the very opposite of practical and experiential. The modern mystical quest is precisely not theoretical. Much modern Christian apologetic exploits this split between the theoretical and the experiential and presents Christianity as a matter of lived experience, not abstract theoretical matters, among which the dogmatic is often included. In the Greek of the Fathers, however, this split can scarcely be represented in words or concepts. Theoretikos means contemplative; that is, seeing and knowing in a deep and transforming way. The ‘practical’, praktikos …, is the personal struggle with our too often wayward drives and desires, which prepares for the exercise of contemplation, theoria; that is, a dispassionate seeing and awareness constituting genuine knowledge, a knowledge that is more than information, however accurate – a real participation in that which is known, in the One whom we come to know. The word theoretikos came to be one of the most common words in Byzantine Greek for designating the deeper meaning of the Scriptures, where one found oneself caught up in the contemplation, theoria, of Christ. The mystical life, the ‘theoretical’ life, is what we experience when we are caught up in the contemplation of Christ, when, in that contemplation, we come to know ‘face to face’ and, as the Apostle Paul puts it, ‘know, even as I am known’ (1 Cor. 13:12).”

The Origins of the Christian Mystical Tradition, pp. 213, 214.

Clément: “The Trinity as Taught by the Church Fathers”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, New Nuggets, The Holy Trinity, Theology on October 1, 2016

Olivier-Maurice Clément (1921 – 2009) – was an Orthodox Christian theologian, who taught at St. Sergius Orthodox Theological Institute in Paris, France. There he became one of the most highly regarded witnesses to early Christianity, as well as one of the most prolific.

“We are made in the image of God. From all eternity there is present in God a unique mode of existence, which is at the same time Unity and the Person in communion; and we are all called to realize this unity in Christ, when we meet him, under the divided flames of the Spirit. Therefore we express the metaphysics of the person in the language of Trinitarian theology. What could be called the ‘Trinitarian person’ is not the isolated individual of Western society (whose implicit philosophy regards human beings as ‘similar’ but not ‘consubstantial’). Nor is it the absorbed and amalgamated human being of totalitarian society, or the systematized oriental mysticism, or of the sects. It is, and must be, a person in a relationship, in communion. The transition from divine communion to human communion is accomplished in Christ who is consubstantial with the Father and the Spirit in his divinity and consubstantial with us in his humanity. […]

In their expositions of the Trinity, St. Basil and St. Maximus the Confessor emphasize that the Three is not a number (St. Basil spoke in this respect of ‘meta-mathematics’). The divine Persons are not added to one another, they exist in one another: the Father is in the Son and the Son is in the Father, the Spirit is united to the Father together with the Son and ‘completes the blessed Trinity’ as if he were ensuring the circulation of love within it. This circulation of love was called by the Fathers perichoresis, another key word of their spirituality, along with the word we have already met, kenosis. Perichoresis, the exchange of being by which each Person exists only in virtue of his relationship with the others, might be defined as a ‘joyful kenosis’. The kenosis of the Son in history is the extension of the kenosis of the Trinity and allows us to share in it.”

From: The Roots of Christian Mysticism, Texts from the Patristic Era with Commentary, pp. 65-67.

Louth: “The Relationship Between Mystical and Dogmatic Theology”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, New Nuggets, Theology on October 1, 2016

Andrew Louth (1944 – ) – is a Christian theologian, Eastern Orthodox priest, and Professor of Patristic and Byzantine Studies at the University of Durham, England. He has taught at Durham since 1996, and previously taught at Oxford and the University of London. Louth is an expert in the history and theology of Eastern Christianity.

“This formative period [1st through 5th centuries] for mystical theology was, of course, the formative period for dogmatic theology, and that the same period was determinative for both mystical and dogmatic theology is no accident since these two aspects of theology are fundamentally bound up with one another. The basic doctrines of the Trinity and Incarnation, worked out in these centuries, are mystical doctrines formulated dogmatically. That is to say, mystical theology provides the context for direct apprehensions of the God who has revealed himself in Christ and dwells within us through the Holy Spirit; while dogmatic theology attempts to incarnate those apprehensions in objectively precise terms which then, in their turn, inspire a mystical understanding of the God who has thus revealed himself which is specifically Christian.

“This formative period [1st through 5th centuries] for mystical theology was, of course, the formative period for dogmatic theology, and that the same period was determinative for both mystical and dogmatic theology is no accident since these two aspects of theology are fundamentally bound up with one another. The basic doctrines of the Trinity and Incarnation, worked out in these centuries, are mystical doctrines formulated dogmatically. That is to say, mystical theology provides the context for direct apprehensions of the God who has revealed himself in Christ and dwells within us through the Holy Spirit; while dogmatic theology attempts to incarnate those apprehensions in objectively precise terms which then, in their turn, inspire a mystical understanding of the God who has thus revealed himself which is specifically Christian.

Put like that it is difficult to see how dogmatic and mystical theology could ever have become separated; and yet there is little doubt that, in the West at least, they have so become and that ‘dogmatic and mystical theology, or theology and ‘‘spirituality’’ [have] been set apart in mutually exclusive categories, as if mysticism were for saintly women and theological study were for practical but, alas, unsaintly men’.” From: The Origins of the Christian Mystical Tradition, p. x

Jean-Claude Larchet: “On the Work of Christ”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, New Nuggets on September 17, 2016

Dr. Jean-Claude Larchet (1949-) – is a French Orthodox researcher who is one of the foremost Orthodox Patristics scholars writing today.

“By His Incarnation, Christ has overthrown the barrier which separated our nature from God and has opened that nature once more to the deifying energies of uncreated grace. By his redemptive work, He has freed us from the tyranny of the devil and destroyed the power of sin. By His death, He has triumphed over death and corruption. By His resurrection, He has granted us new and eternal life. And it is not only human nature, but also the creation as a whole which Christ heals and restores, by uniting it in Himself with God the Father, thereby abolishing the divisions and ending the disorders that reigned within it because of sin.” From The Theology of Illness, pp. 40, 41.

“By His Incarnation, Christ has overthrown the barrier which separated our nature from God and has opened that nature once more to the deifying energies of uncreated grace. By his redemptive work, He has freed us from the tyranny of the devil and destroyed the power of sin. By His death, He has triumphed over death and corruption. By His resurrection, He has granted us new and eternal life. And it is not only human nature, but also the creation as a whole which Christ heals and restores, by uniting it in Himself with God the Father, thereby abolishing the divisions and ending the disorders that reigned within it because of sin.” From The Theology of Illness, pp. 40, 41.

Met. Kallistos (Ware) – “The true aim of theology…”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, New Nuggets, Theology on August 24, 2016

Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia – (b. 1934) is a titular metropolitan of the Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarchate in Great Britain. From 1966-2001, he was Spalding Lecturer of Eastern Orthodox Studies at Oxford University, and has authored numerous books and articles pertaining to the Orthodox faith.

“The true aim of theology is not rational certainty through abstract arguments, but personal communion with God through prayer.”

– Met. Kallistos Ware