Posts Tagged Roman Catholic Theology

David Bentley Hart: “Traditio Deformis – The long history of defective Christian scriptural exegesis occasioned by problematic translations”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ancient Christian Manuscripts, New Nuggets, Theology on March 8, 2026

David Bentley Hart (born 1965) is an American Orthodox Christian philosophical theologian, cultural commentator and polemicist. Here, in one short essay published in “First Things” in May 2015, Prof. Hart addresses, “The long history of defective Christian scriptural exegesis occasioned by problematic translations”.

The long history of defective Christian scriptural exegesis occasioned by problematic translations is a luxuriant one, and its riches are too numerous and exquisitely various adequately to classify. But I think one can arrange most of them along a single continuum in four broad divisions: some misreadings are caused by a translator’s error, others by merely questionable renderings of certain words, others by the unfamiliarity of the original author’s (historically specific) idiom, and still others by the “untranslatable” remoteness of the author’s own (culturally specific) theological concerns. And each kind comes with its own special perils and consequences.

But let me illustrate. Take, for example, Augustine’s magisterial reading of the Letter to the Romans, as unfolded in reams of his writings, and ever thereafter by his theological heirs: perhaps the most sublime “strong misreading” in the history of Christian thought, and one that comprises specimens of all four classes of misprision. Of the first, for instance: the notoriously misleading Latin rendering of Romans 5:12 that deceived Augustine into imagining Paul believed all human beings to have, in some mysterious manner, sinned “in” Adam, which obliged Augustine to think of original sin—bondage to death, mental and moral debility, estrangement from God—ever more insistently in terms of an inherited guilt (a concept as logically coherent as that of a square circle), and which prompted him to assert with such sinewy vigor the justly eternal torment of babes who died unbaptized. And of the second: the way, for instance, Augustine’s misunderstanding of Paul’s theology of election was abetted by the simple contingency of a verb as weak as the Greek proorizein (“sketching out beforehand,” “planning,” etc.) being rendered as praedestinare—etymologically defensible, but connotatively impossible. And of the third: Augustine’s frequent failure to appreciate the degree to which, for Paul, the “works” (erga, opera) he contradistinguishes from faith are works of the Mosaic law, “observances” (circumcision, kosher regulations, and so on). And of the fourth—well, the evidences abound: Augustine’s attempt to reverse the first two terms in the order of election laid out in Romans 8:29–30 (“Whom he foreknew he also marked out beforehand”); or his eagerness, when citing Romans 5:18, to quote the protasis (“Just as one man’s offence led to condemnation for all men”), but his reluctance to quote the (strictly isomorphic) apodosis (“so also one man’s righteousness led to justification unto life for all men”); or, of course, his entire reading of Romans 9–11 . . .

Ah—thereby hangs a tale.

Not that Paul’s argument there is difficult to follow. What preoccupies him is the agonizing mystery that the Messiah has come, yet so few of the house of Israel have accepted him, while so many Gentiles—outside the covenant—have. What then of God’s faithfulness to his promises? It is not an abstract question regarding who is “saved” and who “damned”: By the end of chapter 11, the former category proves to be vastly larger than that of the “elect,” or the “called,” while the latter category makes no appearance at all. It is a concrete question concerning Israel and the Church. And ultimately Paul arrives at an answer drawn, ingeniously, from the logic of election in Hebrew Scripture.

Before reaching that point, however, in a completely and explicitly conditional voice, he limns the problem in the starkest chiaroscuro. We know, he says, that divine election is God’s work alone, not earned but given; it is not by their merit that Gentile believers have been chosen. “Jacob have I loved, but Esau have I hated” (9:13)—here quoting Malachi, for whom Jacob is the type of Israel and Esau the type of Edom. For his own ends, God hardened Pharaoh’s heart. He has mercy on whom he will, hardens whom he will (9:15–18). If you think this unjust, who are you, O man, to reproach God who made you? May not the potter cast his clay for purposes both high and low, as he chooses (9:19–21)? And, so, what if (ei de, quod si) God should show his power by preparing vessels of wrath, solely for destruction, to provide an instructive counterpoint to the riches of the glory he lavishes on vessels prepared for mercy, whom he has called from among the Jews and the Gentiles alike (9:22–24)? Perhaps that is simply how it is: The elect alone are to be saved, and the rest left reprobate, as a display of divine might; God’s faithfulness is his own affair.

Well, so far, so Augustinian. But so also, again, purely conditional: “What if . . . ?” Rather than offering a solution to the quandary that torments him, Paul is simply restating it in its bleakest possible form, at the very brink of despair. But then, instead of stopping here, he continues to question God’s justice after all, and spends the next two chapters unambiguously rejecting this provisional answer altogether, in order to reach a completely different—and far more glorious—conclusion.

Throughout the book of Genesis, the pattern of God’s election is persistently, even perversely antinomian: Ever and again the elder to whom the birthright properly belongs is supplanted by the younger, whom God has chosen in defiance of all natural “justice.” This is practically the running motif uniting the whole text, from Cain and Abel to Manasseh and Ephraim. But—this is crucial—it is a pattern not of exclusion and inclusion, but of a delay and divagation that immensely widens the scope of election, taking in the brother “justly” left out in such a way as to redound to the good of the brother “unjustly” pretermitted. This is clearest in the stories of Jacob and of Joseph, and it is why Esau and Jacob provide so apt a typology for Paul’s argument. For Esau is not finally rejected; the brothers are reconciled, to the increase of both precisely because of their temporary estrangement. And Jacob says to Esau (not the reverse), “Seeing your face is like seeing God’s.”

And so Paul proceeds. In the case of Israel and the Church, election has become even more literally “antinomian”: Christ is the end of the law so that all may attain righteousness, leaving no difference between Jew and Gentile; thus God blesses everyone (10:11–12). As for the believing “remnant” of Israel (11:5), they are elected not as the number of the “saved,” but as the earnest through which all of Israel will be saved (11:26), the part that makes the totality holy (11:16). And, again, the providential ellipticality of election’s course vastly widens its embrace: For now, part of Israel is hardened, but only until the “full entirety” (pleroma) of the Gentiles enter in; they have not been allowed to stumble only to fall, however, and if their failure now enriches the world, how much more so will their own “full entirety” (pleroma); temporarily rejected for “the world’s reconciliation,” they will undergo a restoration that will be a “resurrection from the dead” (11:11–12, 15).

This, then, is the radiant answer dispelling the shadows of Paul’s grim “what if,” the clarion negative: There is no final “illustrative” division between vessels of wrath and of mercy; God has bound everyone in disobedience so as to show mercy to everyone (11:32); all are vessels of wrath so that all may be made vessels of mercy.

Not that one can ever, apparently, be explicit enough. One classic Augustinian construal of Romans 11, particularly in the Reformed tradition, is to claim that Paul’s seemingly extravagant language—“all,” “full entirety,” “the world,” and so on—really still means just that all peoples are saved only in the “exemplary” or “representative” form of the elect. This is, of course, absurd. Paul is clear that it is those not called forth, those allowed to stumble, who will still never be allowed to fall. Such a reading would simply leave Paul in the darkness where he began, reduce his glorious discovery to a dreary tautology, convert his magnificent vision of the vast reach of divine love into a ludicrous cartoon of its squalid narrowness. Yet, on the whole, the Augustinian tradition on these texts has been so broad and mighty that it has, for millions of Christians, effectively evacuated Paul’s argument of all its real content. It ultimately made possible those spasms of theological and moral nihilism that prompted John Calvin to claim (in book 3 of The Institutes) that God predestined even the Fall, and (in his commentary on 1 John) that love belongs not to God’s essence, but only to how the elect experience him. Sic transit gloria Evangelii. I have to say that, as an Orthodox scholar, I have made many efforts over the years to defend Augustine against what I take to be defective and purely polemical Eastern interpretations of his thought, in the realms of metaphysics, Trinitarian theology, and the soul’s knowledge of God (often to the annoyance of some of my fellow Orthodox). But regarding that part of his intellectual patrimony that has had the widest effect—his understanding of sin, grace, and election—not only do I share the Eastern distaste for (or, frankly, horror at) his conclusions; I am even something of an extremist in that respect. In the whole long, rich history of Christian misreadings of Scripture, none I think has ever been more consequential, more invincibly perennial, or more disastrous.

J.B. Heard: Theology Proper

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, The Logos Doctrine (series), Theology on April 27, 2025

Rev. John Bickford Heard (28 Oct 1828 – 29 Feb 1908) was born in Dublin, Ireland. He was a British clergyman and graduate/lecturer at Cambridge University (M.A. 1864). His series of lectures at the Cambridge Hulsean Lectures of 1892-93 served as the basis of his book, Alexandrian and Carthaginian Theology Contrasted, published by T&T Clark, Edinburgh, in 1893. Excerpts below are from this work:

“Nor need we be at a loss for a definition of theology, since the Master has himself deigned to define it. At the crowning stage of His ministry, in summing up all He had been given to teach, He sums it up: “And this is life eternal: that they might know Thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom Thou hast sent.” [John 17:3]

Theology, rightly considered, is the knowledge of God in His relation to us, the cardinal point of which lies in the truth which the old Greek poet [Acts 17:28] had glanced at. “For we are also His offspring” – this is the true keynote; and theology, setting out from this kinship between us and God, we at once soar, as on wings of a spiritual intuition, across the abyss between creature and Creator.”

Op. cit. pp. 31, 32. Brackets [ ] mine.

Christian Theology: Greek East and Latin West Contrasted *

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, Patristic Pearls, Theology on April 8, 2025

Theology is at its best and purest stage when it is intuitive [noetic]; it is based on our spiritual instincts [nous]; its only logic is that best of all logic, when there is one single step, as it has been well said, from the premise to the conclusion.

Eastern Greek theology set out with the doctrine of God in His relation to man. Conversely, Western Latin theology adopted the opposite doctrine of man in his relation to God.

The difference is more than verbal, whether we make man or God the starting-point of our inquiries on this subject. Setting out with man [the Latin model], we have to take him as we find him, blind and insensible to spiritual things. We have to find an explanation for this strange fact – we have to begin with a theory of original sin, a tradition of the fall, and the problem of evil in general. We get out of our depth all at once in a kind of theodicee [theodicy], which lands us at last in a dilemma which no thinker has yet to overcome, and which J.S. Mill admitted to be logically insoluable. Either God is all-goodness, but not all-mighty, or He is all-mighty, but not all-goodness. Pelagians and Augustinians, Arminians and Calvinists, have beaten their wings against the bars of this cage ever since Latin theology replaced Greek [in the Latin West], as it did soon after Augustine’s day, and we are no nearer a solution than ever.

On the other hand, setting out, as the Greeks did, at the other end of the problem, all unfolds itself in a simple and natural order, and there is no room for these gloomy afterthoughts which have made earth a prison-house, and evil a kind of Manichaean partner with good in the government of the universe. Let us notice the order in which the early Fathers of the Alexandrian school [Greek] approached the problem. Their point of departure was the general Fatherhood of God, – of a God, let us add, who was not so much transcendent as immanent in the world [e.g., the Incarnation and His energaeia]. The opening verses of the Gospel of St. John is the key to all that is distinctively Hellenistic in contrast with the Latin or magisterial conception of God. The Logos is σπερματικόσ, or germ-like, in the world: that Logos in man becomes reason or thought in its two-fold manifestation of speech and action. At a loss for a Latin equivalent for the Greek Logos, the Latin mind lost hold of the primitive and deep significance of the thought that there was a Wisdom which was one with God, and yet had its habitation with the children of men.

The Latins, lacking the Logos doctrine, never could see the true grounds of the incarnation which were laid deep in the original and unchangeable relations of God to men… In this point of view Latin theology never has been “rational” in the sense that the early and best type of Greek theology harmonized reason and revelation. To the Hellenistic mind there was no strained reconciliation between reason and faith… The contrast between the two theologies, for which we have to thank Aquinas, the one known as natural and the other as revealed, never so much as occurred to Greek thought when at its best and earliest stage.

History may be said to contain two chapters, and only two – one in which man seeks after God and loses himself in the search; and a second, in which God seeks after man, and seeks, as the shepherd after the lost sheep, until He finds it.

* Excerpted from Alexandrian and Carthaginian Theology Contrasted, John B. Heard. T&T Clark, Edinburgh 1893. Brackets [ ] mine.

Apophatic and Cataphatic Theology: An Issue of Emphasis and Balance

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Contemplative Prayer (series), Ekklesia and church, Essence and Energies (series), First Thoughts, Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, The Cappadocians, Theology on April 6, 2025

Overview

Apophatic and Cataphatic are two terms used in theology to describe different approaches to understanding God. The Eastern Orthodox and Latin West each use both types. The issue comes down to one of emphasis and balance: The Orthodox East is overwhelmingly Apophatic in approach, while the Latin West is predominantly Cataphatic.

Definitions

Apophatic theology (from Greek: ἀπόφημι apophēmi, meaning “to deny”) uses “negative” terminology to indicate what it is believed the divine is not. It means emptying the mind of words and ideas and simply resting in the presence of God. Apophatic prayer is prayer that occurs without words, images, or concepts. This approach to prayer regards silence, stillness, unknowing and even darkness as doorways, rather than obstacles, to communication with God. Apophatic theology relies primarily on experience and revelation.

Cataphatic theology (from the Greek word κατάφασις kataphasis meaning “affirmation”) uses “positive” terminology to describe or refer to the divine, i.e. terminology that describes or refers to what the divine is believed to be. Cataphatic prayer is prayer that speaks thoroughly, intensively, or positively of God: prayer that uses words, images, ideas, concepts, and the imagination to relate to God. Cataphatic theology relies heavily on logic and reason.

Background

Apophatic theology—also known as negative theology or via negativa—is a theology that attempts to describe God by negation. In Orthodox Christianity, Apophatic theology is based on the assumption that God’s essence is unknowable or ineffable and on the recognition of the inadequacy of human language to describe God. The Apophatic tradition in Orthodoxy is balanced with Cataphatic theology (positive theology) via belief in the Incarnation and the self-revealed energies of God, through which God has revealed himself in the person of Jesus Christ. However, Apophatic theology is the dominant traditional Eastern paradigm of an experiential, revealed theology, intimately linking doctrine with contemplation through purgation (catharsis), illumination (theoria), and union (theosis).

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – 215) was an early proponent of Apophatic theology with elements of Cataphatic. Clement holds that God is unknowable, although God’s unknowability, concerns only his essence, not his energies, or powers. According to Clement’s writings, the term theoria develops further from a mere intellectual “seeing” toward a spiritual form of contemplation. Clement’s Apophatic theology or philosophy is closely related to this kind of theoria and the “mystic vision of the soul.” For Clement, God is both transcendent in essence and immanent in self-revelation.

The Cappadocian Fathers (Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus (4th century)) were early exemplars of this Apophatic theology. They stated that mankind can acquire an incomplete knowledge of God in his attributes, positive and negative, by reflecting upon and participating in his self-revelatory operations (energeia). But, the essence of God is completely unknowable.

A century later Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (late 5th century) in his short work Mystical Theology, first introduced and explained what came to be known as Apophatic or negative theology.

Maximus the Confessor (7th century) maintained that the combination of Apophatic theology and hesychasm—the practice of silence and stillness—made theosis or union with God possible.

John of Damascus (8th century) employed Apophatic theology when he wrote that positive (cataphatic) statements about God reveal “not the nature, but the things around the nature.”

All in all, Apophatic theology remains crucial to much of the theology in Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The opposite tends to be true in Western Latin Christianity, with a few notable exceptions to this rule.

Cataphatic theology

In the Latin West a heavily Cataphatic theology, or via positiva, developed, which remains today in most forms of Western Christianity. This type of Cataphatic theology is based on using human reason to make positive statements about the nature of God. It slowly developed from the 5th to the 11th century, emerging as Scholasticism in the Medieval Period (11th-17th centuries). (see entries for Anselm and Thomas Aquinas, below)

Augustine of Hippo (354–430) significantly influenced scholasticism, emphasizing the integration of faith and reason. His ideas laid the groundwork for later Scholastic thinkers who sought to reconcile Christian theology with classical philosophy, particularly through dialectic reasoning. Augustine’s doctrines of the filioque, original sin, the doctrine of grace, and predestination found little support outside of the Western Roman Church. Within the Western Latin church, ‘Augustinianism’ dominated early theology.

Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033 – 1109) is widely considered the father of Scholasticism, endeavoring to render Christian tenets of faith, traditionally taken as a revealed truth, as a rational system. Scholasticism prescribed that Aristotelian dialectic reason be used in the elucidation of spiritual truth and in defense of the dogmas of Faith.

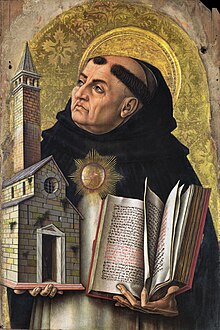

Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225 – 7 March 1274) reflects the mature emergence of this new medieval Scholastic paradigm, which promoted the use of formal intellectual reason, putting it at odds with the predominantly Eastern revealed tradition of hesychastic contemplation. Aquinas’ Summa Theologica (1265–1274), is considered to be the pinnacle of Medieval Scholastic Christian philosophy and theology. The resulting ‘Thomism’ remains the foundation of contemporary Western Latin theology.

The Apostle Paul: Radical, Conservative, or Reactionary?

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ancient Christian Manuscripts, Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Theology, Women in Early Christianity on March 21, 2025

The Apostle Paul is a controversial figure. More than half of the New Testament is written by him, about him, or in his name. There is a general consensus among contemporary scholars that the Apostle Paul did not write all 13 New Testament letters attributed to him.

Modern scholarship attributes seven of Paul’s 13 canonical letters as unquestionably authentic:

- Romans,

- Galatians,

- I Corinthians,

- II Corinthians,

- I Thessalonians,

- Philippians, and

- Philemon

Three others are generally considered deutero or (pseudo) – Pauline and are Pauline in theology, with a couple of notable exceptions, but are different in style and much more mainline and conservative in tone than the undisputed letters. They were probably written in the generation after Paul’s death by people very familiar with his teaching. The deutero (or pseudo)-Pauline letters are:

- Colossians,

- Ephesians, and

- II Thessalonians

The last three, the “Pastoral Letters”, are largely considered pseudepigrapha (a bible scholar’s politically-correct term for “forgery”) and were probably written around the beginning of the 2nd century and exhibit patriarchal, sexist, and reactionary social attitudes one would expect of an entrenched Greco-Roman cultural institution (exactly what the early Church was becoming by that time).1,2 The pseudepigraphical letters are:

- I Timothy,

- II Timothy, and

- Titus

What follows are estimates of the percentages of biblical scholars who reject Paul’s authorship of the six books in question:

- 2 Thessalonians = 50 percent;

- Colossians = 60 percent;

- Ephesians = 70 percent;

- 2 Timothy = 80 percent;

- 1 Timothy and Titus = 90 percent.2

In addition to judgments about entire letters, scholars also question the authorship of certain passages in the undisputed letters. Post-Pauline texts are those alleged to have been inserted into a letter after its composition and are generally called scribal “interpolations”.

Among the passages that some scholars label as interpolations are:

- Romans 5:5-7, 13:1-7, 16:17-20, 16:25-27;

- 1 Corinthians 4:6b, 11:2-16, 14:33b-35 or 36;

- 2 Corinthians 6:14-7:1; and

- 1 Thessalonians 2:14-16.2,3

Given the above, one could argue that there are really three “Pauls” in the New Testament:

- The Radical Paul of the seven undisputed authentic letters

- The Conservative Paul of the three deutero-Pauline letters

- The Reactionary Paul of the three pseudepigraphical Pastoral Letters

___________________________________________________________

- The First Paul, Reclaiming the Radical Visionary Behind the Church’s Conservative Icon, By Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan , 2009 HarperCollins, NY, NY

- Apostle of the Crucified Lord, A Theological Introduction to Paul & His Letters, by Michael J. Gorman, 2004 Wm. B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI / Cambridge, UK

- The Authentic Letters of Paul, A New Reading of Paul’s Rhetoric and Meaning, by Arthur J. Dewey, Roy W. Hoover, Lane C. Mc Gaughy, and Daryl D. Schmidt, 2010 Polebridge Press, Salem, OR

“And we believe in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church.”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, First Thoughts, Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, Monasticism on December 28, 2024

In the original koine Greek of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed of AD 381, the subject line reads: Εἰς μίαν, Ἁγίαν, Καθολικὴν καὶ Ἀποστολικὴν Ἐκκλησίαν.

I find it sadly ironic that The Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, as it is recited in most worship services today, uses the first person singular (“I believe…”/”Πιστεύω”) rather than the first person plural (“We believe…”/”Πιστεύομεν”) as it was enacted at the first and second ecumenical councils (Nicaea AD 325 and Constantinople AD 381) of the undivided Church. In this self-centered, affluent, secularized, and fragmented Western world, I guess the shift from a collective “we” to an individual “I” should come as no surprise.

Christianity became the State Religion of the Roman Empire in AD 380. Since becoming that key religious institution in the social and political infrastructure of worldly power, very little has changed to this day, regardless of the form or character of the Church’s earthbound imperial partners. Fr. Richard Rohr, OFM, calls it the Church’s 1,700 year addiction to Power, Prestige, and Possessions.

Let’s analyze our subject line from the Creed: “And we believe in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church.”

The institutional Christian Church was no longer “One” after 451 AD; increasingly less “Holy” after 313 AD; no longer “Catholic” after 1054 (worse after 1517); and “Apostolic” only in origin (and Rome’s claim to Peter and Constantinople’s claim to Andrew are tenuous, at best.). So, nothing in this line from the Creed has been objectively true in more than 1,000 years. Reciting this line from the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed now is not so much a proclamation of faith, as a largely an unsupportable exercise in wishful thinking. Don’t believe it? “Google” the dated Church events and read for yourself.

Until the issues raised in the preceding paragraphs are meaningfully addressed (read: confession and repentance) by the legacy institutional Church, I think it will continue to shrink in numbers, authority, influence, and credibility. I believe the Ecclesia (Ἐκκλησία) of scripture will endure and eventually prevail; the institutional imperial Church, not so much. And Ecclesia and Church are not the same thing, in spite of institutional protests to the contrary.

In the meantime, solitary Christian hermits patiently remain in silent prayer within their virtual deserts.

Prayer Ropes and Rosaries

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, Hesychasm - Jesus Prayer, Monasticism, New Nuggets, Patristic Pearls on December 21, 2024

Both the prayer rope and the rosary are revered traditional aids to Christian prayer, yet each has its own unique origin, symbolism, and devotional use.

The Prayer Rope, now largely associated with the Eastern Orthodox Church, is a loop of knots (each knot containing seven crosses), usually made of wool, that is used to focus and intensify prayer, particularly the Jesus Prayer. It acts as a physical guide for a repeated, meditative style of prayer, allowing practitioners to keep count while reflecting and meditating. The prayer rope has its beginnings in early fourth century Christian monasticism in the Egyptian Desert, where it was devised as a tool to aid in the ascetic practice of continuous prayer (1 Thes. 5:17).

Origins: The prayer rope is known as a ‘komboskini’ in Greek and ‘chotki’ in Russian. The prayer rope owes its origins to St. Pachomius the Great, a fourth century “Desert Father” in upper Egypt and founder of cenobitic monasticism (a monastic tradition that stresses community life, over the older, eremitic, or solitary tradition). St. Pachomius established the prayer rope as a practical solution for the monks under his supervision to count prayers and prostrations consistently. The prayer rope evolved as a useful instrument for monks to keep track of their prayers, particularly the Jesus Prayer, without distraction. It gradually took on a deeper spiritual value, with each knot symbolizing a request for mercy and humility.

Symbolic Significance: Wool knots, each knot containing seven crosses, are commonly used on traditional prayer ropes to represent Christ’s flock and the shepherd’s care. The number of knots in a prayer rope varies; typically 33 (Christ’s age at crucifixion), 50, or 100.

Traditional Use: In Orthodox Christian practice, the prayer rope is typically used for private prayer in reciting the Jesus Prayer, acting as a physical and spiritual guide to help the mind (nous) and heart concentrate on prayer.

The Rosary, strongly associated with the Roman Catholic Church, is a string of beads that ends with a crucifix and is used to guide Catholics through a sequence of prayers that reflect on the lives of Christ and the Virgin Mary. Each bead signifies a specific prayer, such as the Hail Mary, and each set of beads makes a ‘decade’ that corresponds to a mystery in Christ’s life. The rosary has a long history, dating back to the Middle Ages when it first arose as a popular form of laity devotion, eventually becoming a prominent practice in Catholic piety.

Origins: The rosary is typically identified with Saint Dominic in the early 13th century. The rosary began as a simple way for lay people to join in the monastic practice of reciting the Psalms, but has since evolved into a systematic form of prayer. The rosary prayers are split into decades, each with ten Hail Marys, an Our Father, and a Glory Be, and are frequently accompanied by meditations on the Mysteries of the Rosary.

Symbolic Significance: Each rosary bead represents a prayer as well as a step in the meditation journey through Jesus Christ’s and the Virgin Mary’s lives. The rosary culminates with a crucifix, which represents Christ’s sacrifice.

Traditional Use: Roman Catholics utilize the rosary for both personal meditation and social worship. It is frequently prayed privately for personal spiritual development or in groups for social objectives and celebrations.

Thomas Aquinas: “… all that I have written seems to me as so much straw”

Posted by Dallas Wolf in First Thoughts, Theology on December 10, 2024

Thomas Aquinas OP (c. 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest, the foremost Scholastic thinker, as well one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the Western tradition. Thomas’s best-known work is the unfinished Summa Theologica, or Summa Theologiae (1265–1274). As a Doctor of the Church, Thomas Aquinas is considered one of the Roman Catholic Church’s greatest theologians and philosophers.

On December 6th, 1273, while Thomas Aquinas was celebrating Holy Communion during the Feast of Saint Nicholas, he received a revelation that so affected him he called his principal work, the Summa Theologica, nothing more than “straw” and left it unfinished.

Aquinas described his Divine Experience: “The most perfect union with God is the most perfect human happiness and the goal of the whole of the human life, a gift that must be given to us by God.”

When his friend and secretary tried to encourage Aquinas to write more, he replied:

“I can do no more. The end of my labors has come. Such things have been revealed to me that all that I have written seems to me as so much straw. Now I await the end of my life after that of my works.”

Aquinas would die just three short months later. The Great Doctor finally got it right, I think. Experience (theoria) trumps reason.

Rohr: Power, Prestige, and Possessions; Major Obstacles to the Reign of God

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Ekklesia and church, New Nuggets on November 28, 2024

Fr. Richard Rohr – is a Franciscan priest, Christian mystic, and teacher of Ancient Christian Contemplative Prayer. He is the founding Director of the Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, NM.

In Jesus’s consistent teaching and in Mary’s great Magnificat, both say that there are three major obstacles to the coming of the reign of God. I call them the three P’s: power, prestige and possessions. Mary refers to them as “the proud,” “the mighty on thrones” and “the rich.” These, she says, God is “routing,” “pulling down” and “sending away empty.” (This great prayer of Mary was considered so subversive by the Argentine government that they banned it from public recitation at protest marches!) We can easily take nine-tenths of Jesus’s teachings and very clearly align it under one of those three categories: Our attachments to power, prestige and possessions are obstacles to God’s coming. Why could we not see that?

—from the book Preparing for Christmas: Daily Meditations for Advent

by Richard Rohr

The Seven Ecumenical Councils

Posted by Dallas Wolf in Council of Chalcedon, Ekklesia and church on February 3, 2023

A Church Council is an official ad hoc gathering of representatives to settle Church business. Such Councils are called rarely and are not the same as the regular gatherings of church leaders (synods, etc.). An ecumenical council is one at which the whole Church is represented. The three major contemporary branches of the Church (Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Protestant) recognize seven ecumenical councils: Nicea (325), Constantinople (381), Ephesus (431), Chalcedon (451), Constantinople II (553), Constantinople III (680), Nicaea II (787). Further ecumenical councils were rendered impossible by the widening split between Eastern Orthodox (Greek speaking) and Roman Catholic (Latin speaking) Churches, a split that was rendered official in AD 1054 and has not yet been healed.

Note: In addition to these universally-acknowledged councils, the Roman Catholic Church recognizes a further fourteen ecumenical councils: Constantinople IV (869-70), Lateran I (1123), Lateran II (1139), Lateran III (1179), Lateran IV (1215), Lyons I (1245), Lyons II (1274), Vienne (1311-12), Constance (1414-18), Florence (1438-45), Lateran V (1512-17), Trent (1545-63), Vatican I (1869-70), Vatican II (1965). But these were councils of only the Catholic Church, and are not recognized by the Orthodox or Protestant Churches.

The Council of Nicaea, 325

In 324 Constantine became sole ruler of the Roman Empire, reuniting an empire that had been split among rival rulers since the retirement of Domitian in 305. Constantine, the first Christian emperor, reunified the empire but found the Church bitterly divided over the nature of Jesus Christ. He wanted to reunify the Church as he had reunified the Empire. The major dispute was over the teaching of Arius, but there were other doctrinal issues also.

- Arianism: teaching of Arius of Alexandria (d. 335), who believed that Jesus Christ was created ex nihilo (out of nothing) by the Father to be the means of creation and redemption. Jesus was fully human, but not fully divine. He was elevated as a reward for his successful accomplishment of his mission. The Arian rallying cry was “There was a time when the Son was not.”

- Monarchianism: defended the unity (mono arche, “one source”) of God by denying that the Son and the Spirit were separate persons.

- Sabellianism: a form of monarchianism taught by Sabellias, that God revealed himself in three successive modes, as Father (creator), as Son (redeemer), as Spirit (sustainer). Hence there is only one person in the Godhead.

Constantine summoned the bishops at imperial expense to Nicea, 30 miles from his imperial capital in Nicomedia. Here they were to settle their differences in a council over which he presided. The council rejected Arianism. The Council issued a creed based upon an existing baptismal creed from Syria and Palestine. This creed became known as the Nicene Creed, or Confession of the Faith.

The Council also issued a set of canons, primarily dealing with church order.

The Council of Constantinople, 381

The second council met in Constantinople, the new imperial capital. The council issued a new creed, clarifying the understanding of the Holy Spirit as a co-equal Person of the Trinitarian Godhead as expressed in the Nicene Creed adopted in 325. This creed became known as the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed and remains the Confession of the Faith today in the Eastern Church.

Later, the Roman Church, under the influence of the Franks in the 8th century, unilaterally added a single word to the Creed, inserting Filioque “and the Son” to the statement about the Spirit, so as to read “the Spirit…proceeds from the Father and the Son.” In 867 the Patriarch of Constantinople declared Rome heretical for unilaterally inserting this clause into the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed. To this day the Western Church (Roman Catholic and Protestant) accepts the filioque clause, while the Eastern Church (Orthodox) does not.

The Council of Ephesus, 431

Condemned Nestorius and his teaching (Nestorianism) that Christ had two separable natures, human and divine. Declared Mary to be theotokos (lit. God-bearer, i.e., Mother of God) in order to strengthen the claim that Christ was fully divine.

The Council of Chalcedon, 451

Issued the Chalcedonian Formula, affirming that Christ is two natures in one person.

The Council of Constantinople II, 553

Condemned the Three Chapters, which emphasized Christ’s humanity at the expense of his deity. Their opponents held Alexandrian theology emphasizing Christ’s deity.

The Council of Constantinople III, 680

Condemned monothelitism (Christ has a single will), affirming that Christ had a human will and a divine will that functioned in perfect harmony.

The Council of Nicea II, 787

Declared that icons are acceptable aids to worship, rejecting the iconoclasts (icon-smashers)